It is hard not to be taken in by the energy of Kailash-Manasarovar. Even an atheist like

Over the years I made trips to locate the sources of the four rivers, view Kailash’s east face, do the inner parikrama, cross the Khado Sanglam La, and visit a host of significant places linked to the myth of Meru—that colossal mountain at the centre of Creation, of which Kailash is supposed to be the earthly manifestation.

Somewhere, caught up in all this energy, I came upon an account of the freezing of the lakes Manasarovar and Rakshas Tal in the writings of the eclectic Swami Pranavananda. A regular visitor to the region, he witnessed the event in the winter of 1936–37, during a year-long stay at Thugolho Gompa.

The Swami rose on December 28, 1936, sensing something had happened—“There was pin-drop silence everywhere. Like the eternal silence of Nirvana there was perfect stillness all around.”

Climbing up to the monastery’s terrace, he realised that the lake had frozen a mile from the shore. (Two days later, the entire lake turned solid.) With this “there had descended a thorough change in the whole atmosphere (physical, mental and spiritual)”. The experience moved him deeply. “Tears of joy trickled down the cheeks, only to be frozen on the parapet.”

His description of the frozen lakes, and his adventures that winter had me hooked! Can lakes that size freeze over? Quite unimaginable. Yet, he said they do, and, what’s more, solidly enough to support the weight of a human being. He made a tentative crossing on foot across the northwest corner of Manasarovar, but later visited two islands in Rakshas Tal, during a journey across the lake, that he made riding a yak! This had to be experienced to be believed.

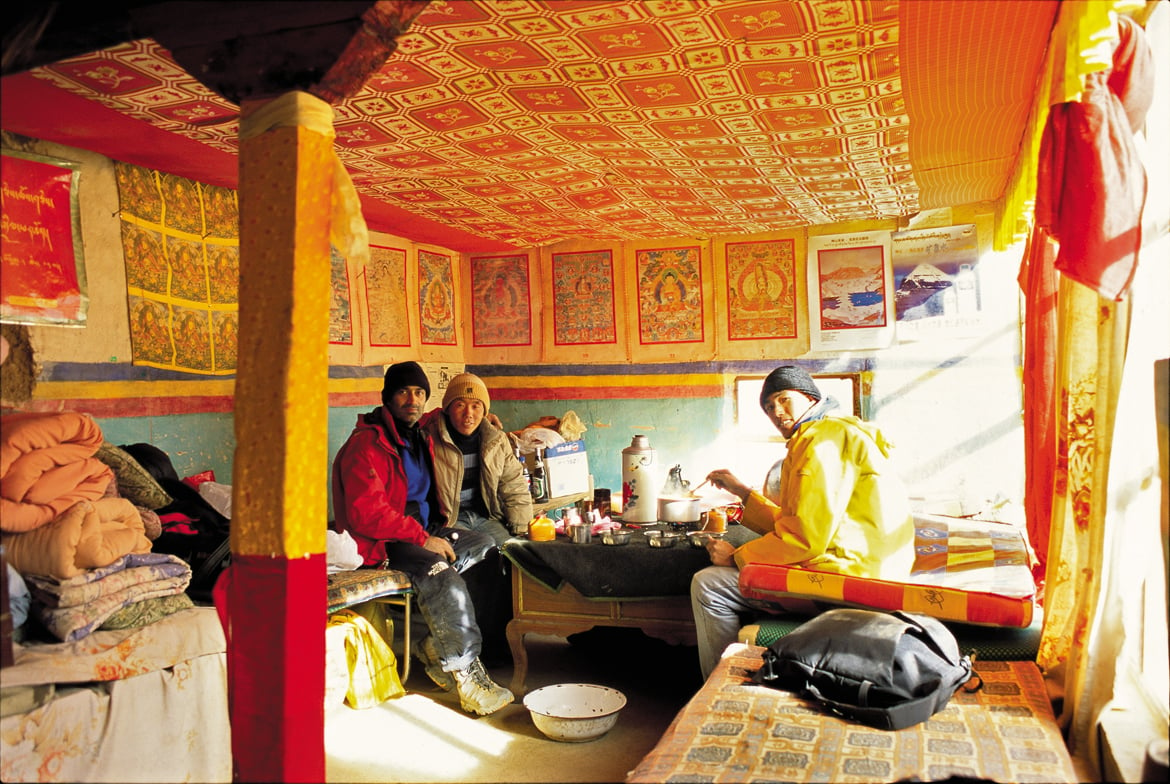

In 2006, after years of trying, I finally got a permit, and made my way to this corner of southwest Tibet. These are images from that visit. And, yes, the experience was every bit as magical as the Swami described.

Photo Essays

Mt Kailash

travel