Life is a journey, not a destination…” and every other beleaguered traveller’s cliche` that you have ever

DOWN MEMORY LANE…

There are no exact dates for when the original GT Road came into existence. However, the earliest written reference to sarais dates from the reign of Muhammad bin Tughlak (1324-51), who ordered that a sarai be built at each stage between Delhi and his new capital, Daulatabad. When the 16th-century ruler Sher Shah Sur gets credit for ‘building’ the GT Road, it merely means that he knitted all the existing roads along the route together. He also issued laws for the protection of the road and is said to have commissioned as many as 1,700 sarais along the major routes.

Mughal emperors Akbar and Shah Jahan expanded the concept, and even Aurangzeb — who never showed any interest in going down in history as a nice man — spent good money on sarais. And when the British came, they modernised this road, building bridges and railway lines, for military purposes, if not entirely for the good of pigmented humanity.

A LOST KOS…

Our journey is aimed at coaxing the road to give up its secrets. You do need to keep your eyes peeled on this journey and not pelt along at 120 kmph (though the road tempts you to do just that) if you want to see anything worthwhile. Initially we got excited by anything, even brick-kilns, and screamed “kos-minar”. A kos-minar is a glorified medieval milestone about 15-20 ft tall. A kos is roughly equal to 3 km and minar is a pillar.

Our first major sighting came a little before Panipat. Some 94 km from Delhi, a kos-minar hugs the right-hand side of the road for dear life. Most of the kos-minars along this road lie abandoned, even being pulled down when roads are widened.

At Gharaunda, some 120 km from Delhi, we saw our first sarai. Built during Shah Jahan’s reign, in 1632, by Khan Feroze, it has been engulfed by the town and only the two huge gateways remain, one dilapidated and the other still impressive, with the arches and the central dome bespeaking Mughal grandeur.

Following instructions, we look out on our left for the Liberty Leather factory just outside Gharaunda, almost immediately after which we spot a kosminar sitting amidst verdant fields, for all the world like a poet wandering off for inspiration.

Madhuban is the next stop. We hunt in vain for a medieval bridge dating back to Sher Shah’s reign and then realise that some bright fellow, probably from the PWD where such brightness usually resides, has whitewashed it. A rusty old ASI board confirms its antecedents. The mazhar (a Sufi saint’s shrine) adjacent to it is the resting place of no less than five pirs and is known as the Pucce Pul ke Pir. When the bridge was being built, the locals say, the contractor was baffled because it would keep collapsing despite his best efforts. Finally, he decided to build the mazhar first. When he next built the bridge, it held, and has done so for all these centuries.

By the time we reach Ambala, it is drizzling again. We make a small detour, taking refuge in St Paul’s Cathedral, which falls within the Air Force Public School compound in the Ambala Cantonment. It is an incredibly graceful structure, though little remains of it now. Some 20 km from Ambala is the Shambhu Sarai. Initially built by Sher Shah, it’s very size catches your eye from the main road. This is the first largely intact sarai that one comes across, complete with well-maintained lawns, 140 rooms, a well, a mosque and a baradari.

A couple of kilometres further on is the Sarai Lashkari Khan, its arched gateways completely abandoned to the elements — bereft even of the ubiquitous ASI blue board. And the land between the two gateways is being farmed by the villagers! An old cropper tells us that it was built by Aurangzeb around 1702 and named for the village. He says there was a dispute over the site and a 1962 High Court judgement awarded all the ground space inside the building to the village while the structure was given over to ASI! We knew that the law was an ass. Didn’t know there was proof.

Halting at Amritsar for the night, the next day we take a detour on the original route of the GT Road, a slight deviation from the current one heading for Chabal (take the road opposite Lahori Gate at Amritsar). The rain has finally let up and munching on guavas dredged in masala slapped on them, we begin our usual quest — this time for Sarai Amaanat Khan Gaon. (Once at Chabal, ask for Attari Road.)

ALIVE IN MEDIEVAL INDIA…

Whatever we had expected of the sarai, it was certainly not to find it inhabited. About 500 people live inside it, and an old Sikh tells us that their forefathers have been here for “400 to 500 years”. Built by Amaanat Khan, the calligrapher of the Taj Mahal (who lived here for a while and is buried outside), this is truly a ‘living’ sarai. The residents have even added on their own construction, so a house here can actually have a 500-year-old wall and a 10-year-old ceiling!

We pass Rajataal en route to Attari, where an abandoned masjid stands near an army base, only its brilliant indigo, green and yellow tile-work surviving. Attari itself is rich in Sikh history. The fort built by General Sham Singh Attari, the famous general, survives, but is fast disintegrating. From there, the Wagah Border is practically a hop, skip and a jump away.

Retracing our steps to Chabal, we pass an old tank at Naurangabad, which is said to be from Sher Shah Sur’s reign and was restored by two Sikh widows in the 19th century. We pass another kosminar on our way to Fatehabad, crossing Tarn Taran, and are promptly flagged down for a friendly langar.

SEVEN MOSQUES AND A FARMER…

The Fatehabad Sarai boasts a glazed-tile patterned gateway in rich blues, yellows and greens. It is also home to seven old mosques. The keys to the one truly worth visiting are with the family of Parkar Singh Tovat, a farmer next door. The mosque’s façade is embellished with calligraphy and floral motifs on plaster, but it is the inner dome that is stunning, with rich mineral colours surviving the ravage of the years.

Twenty minutes away is Goindwal Sahib, where the Sikh guru, Angad Dev, built an 84-stepped baoli. Sikhs hold that anyone reciting the Japji Sahib on each step will be freed from the cycle of 84,00,000 rebirths.

We halt at Kapurthala for the night. Next day the road to Nakodar is rich with possibilities and we scent our way to Mallian Kala. At Dakhni Sarai, surrounded by lush greenery, restoration work is in progress. Built in 1640 by Ali Mardan Khan, Shah Jahan’s general, the 124-cell sarai is still vibrant, though nowhere near Alexander Cunningham’s 1904 description: “The interior surface of the gateways is covered with brilliantly coloured tile work of the mosaic variety.”

BY ORDER OF AN EMPRESS…

Another kos-minar and we find ourselves in Nakodar, at the famed Ustad-Shagird Tombs, built during the reigns of Jahangir and Shah Jahan (1612 and 1657) respectively. Set in well-maintained grounds, the first tomb is of the musician Muhammad Momin Hussain, who has been listed in the Ain-i-Akbari as a Navratna at Akbar’s court. Haji Jamal, his pupil, is buried in the facing tomb, which inverts the octagonin-square pattern of his teacher’s tomb.

A few kilometres east of Nakodar, en route to Phillaur, is Nurmahal, one of the most beautiful sarais on this road. Commissioned “ba hukam Nur Jahan Begum” (by the order of Empress Nur Jahan), it was executed by Nawab Zakariya Khan, of the Jalandhar Province in 1619-1621. Sacked twice by invaders, little remains of this, apart from the exquisitely worked gate.

The “Emperor’s [Jahangir] magnificent three-storeyed apartment which formed the centre block of the south side”, noted by Cunningham, is now derelict. With its 140 rooms, it had formerly provided accommodation for Jahangir’s personal entourage of a hundred people. Nurmahal is now bisected by an ugly wall — in one half, a local primary school is being run, while most of the other half has been taken over by a police station! And no sign remains of Zakariya Khan admonishing his faujdars, “Taking payment from travellers is forbidden… Should any officer collect these dues, may his wives be divorced.” This inscription on the sarai walls dramatically ended in “talaq, talaq, talaq”!

Apart from its beautiful sculptureladen gateway, the only vestige of the erstwhile grandeur of the sarai is a popular saying in the region, ‘Kya koi Nurmahal ki sarai bana rahe ho?’ (Are you building the Nurmahal Sarai itself?), to anyone with particularly grandiose plans for a building.

BUFFALOES ON THE WAY HOME…

At Phillaur, we move over to the GT Road again. On the Ludhiana-Khanna stretch, look out for the kos-minar hugging the right verge of the road.

Doraha is home to an eponymous sarai. Since it is not visible from the road, you’ll have to be persistent with your enquiries. In a merging of the past with the present, the Mughal-era flowerbed outside the masjid is being maintained. Although reduced to being serenaded by buffaloes, the eight-petalled indigo, blue and yellow floral tile-pattern on the gateway is still brilliant and worth the trip.

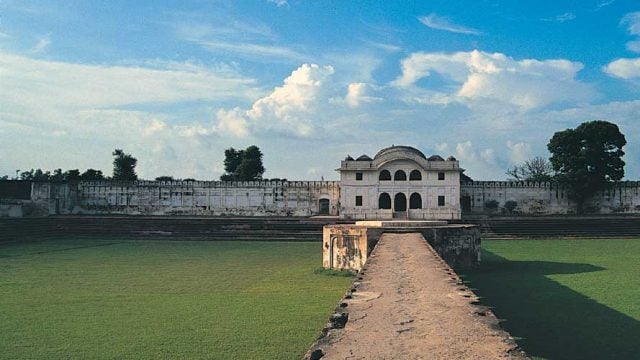

Sirhind, just over 60 km from Doraha, is a destination by itself. Home to the grand Sarai Aam Khas Bagh, which at its prime stretched for over a mile in length, the name Aam Khas denotes that it was used both by royalty and commoners. ‘Bagh’, of course, refers to the lush gardens it is set in. The Sheesh Mahal, with its silvered dome; Gulabveda, with the Mehtaabi Chabutra where the emperor would savour full-moon nights; the ingenious heating and cooling arrangements in the Aram Gah Muqquaddas and Sarad Khana respectively; the waterfalls and lawns —all seduce a tired traveller. Most of it was laid waste by the Sikh hero Banda Bahadur to avenge the martyrdom of Guru Gobind Singh’s sons.

Journeys, even those without destinations, have to break for a while, if not end. And so, it was back to the midnight fumes of Delhi after the lush fields of Punjab’s villages….

Badshahi Road

Drives

Fatehabad Sarai