How do you say ‘I love you’ in Russian?” asked the guide. I squinted with suspicion at

It’s true. Russians are awkward in the humour department.

I had always been a little sceptical about travelling to Russia—it hadn’t featured on my list of places to go to before I die, and my knowledge was restricted to Putin, Stalin, freezing Siberia, vodka, Matryoshka dolls and Boney M’s Rasputin.

But this summer’s sojourn to Russia threw all my inhibitions out the window when I found myself there to mark the centenary of the Russian Revolution.

A ROAD TRIP

My first encounter with a Russian on this trip was at border control, when our bus drove in from Helsinki. With a smile, I handed over my passport to the stone-faced official who proceeded to scan me up and down as if she were a KGB agent.

I was later informed that the Russian smile was as rare as the blue moon.

For the most part, the three-hour drive from the EU border was uneventful and a little bumpy—our tour guide had warned us so, but it was nothing a hardened Indian couldn’t take. The countryside changed from thick forests to rolling hillocks with dilapidated houses, scattered here and there—vestiges of Russia’s communist past.

During the height of communism, all its citizens were given accommodation, which is why most Russians today pay for utilities only and not rent. In cities like St Petersburg and Moscow, these apartments are tiny, but the countryside has big houses, which are falling into disrepair because their owners don’t have the means to renovate.

One minute I was staring sleepily at the crummy houses and the next, BOOM! St Petersburg exploded right in front of me. At first, its wide roads and skyscrapers made it seem like any modern city; soon fancy cars were replaced by vintage 1970s Ladas and tall buildings with imperial Italian architecture. St Petersburg is European paradise.

GRAND BEGINNINGS

Built on a swamp, the erstwhile capital of the Russian Empire was christened St Petersburg after its patron saint and was intended to be a testament to the Romanovs’ growing status in the world. Tsar Peter the Great and successors were Westward-looking, employing a number of architects from across Europe to add extravagance to the city.

Our visit started at the Peter and Paul Fortress, a former prison fortress and the nucleus of the city founded by Tsar Peter in 1703. The city’s oldest landmark, the stunning European-styled Peter and Paul Cathedral is famously known for its 404-foot-long golden spire that can be seen from almost anywhere in the city.

Ironically, the cathedral became the resting place of most Romanovs after a firing squad executed the family at the onset of the Bolshevik Revolution in November 1917.

Guides will brush past the fact that both Leon Trotsky and Lenin’s brother, Aleksandr Ulyanov, were incarcerated in the fortress. Communism is a touchy topic with most Russians, and it’s best not to talk politics with locals.

THE TSARINA’S TREASURE

If you were impressed by the Louvre or the Vatican Museums, the Hermitage Museum will leave you astounded. This regal green, white and gold structure wraps itself along the edge of the Neva River like a necklace that seems to hypnotise the unsuspecting visitor.

It is difficult to describe the moment I crossed the ticket barrier to ascend the grand staircase—an explosion of gold and marble beyond my wildest dreams. Three hours were spent barely skimming the 360 elaborate rooms which house more than three million artefacts ranging from various Picassos and Rembrandts to early Stone Age tools, Egyptian obelisks and more—all part of a collection of the promiscuous Tsarina Catherine the Great, who commissioned the museum in 1764. But that’s only a fraction of the riches on display; there’s about 20 times more housed in vaults.

What is truly amazing is the fact that Russia’s treasures managed to survive since they were hurriedly shipped off to Siberia for safekeeping during World War II, far away from Hitler’s hands. Still, many were lost to obscurity.

THE ‘BLOODY’ CHURCH

The Church of the Saviour on Spilled Blood is perhaps Russia’s most iconic, having been built on the site of Tsar Alexander II’s 1881 assassination. Outside, it is a medley of colourful lollipop-like domes, hardly reflective of the church’s dark beginnings; inside, thousands of stones like lapis lazuli and jasper intermingled with gold make up the 7,500 sq ft of mosaics, linking the story of Alex’s murder to the resurrection of Christ.

Back in the good old communist days, churches were razed to the ground since religion had no business existing. The remaining ones like this were relegated to food shelters. For years, putrid potato crop had ruined the church, and it was only after years of restoration that the structure regained its former glory.

Bombs during World War II did strike the church, but thankfully didn’t cause much damage—if you squint at Jesus right above the altar, you can just about make out a crevice under his arm where an explosive was lodged. Hand of God?

VENICE OF THE NORTH

I couldn’t have asked for a better end to a trip as I cruised down one of the many canals on the Neva River which has a whopping 342 bridges, comparable to Venice. The red sunset, the shampanskoye and the vodka, the smelly caviar, the lone man running along the canal trying to keep up with our boat—it was all unforgettable.

But I couldn’t help noticing crumbling apartment complexes juxtaposed with the imperial remnants of the Russian Empire, reminders that even this regal city had something to hide. That’s a mystery I reserved for another visit.

As Churchill rightly exclaimed, “Russia is a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma.” St Petersburg is exactly that—a city that has changed as many times as its name and yet seems to be frozen in time.

For one last visual treat, our guide pointed out a former KGB building, which totally eluded me, and cracked a ‘joke’ which I am still trying to figure out.

Oh, those Russians!

Inayat Naomi Ramdas is a digital nomad, and a history and language aficionado. When she is not planning her next adventure, she can be found trying to find a good cup of coffee.

St Petersburg

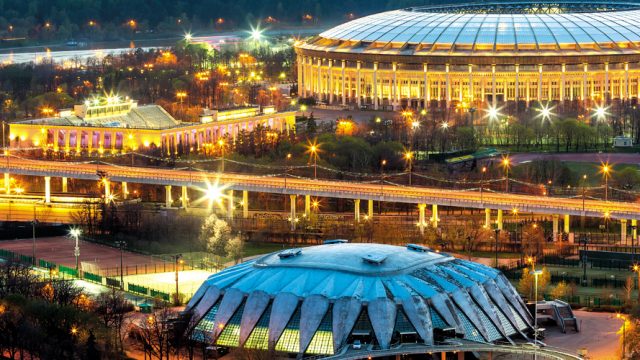

Moscow

Hermitage Museum