Lothal is located between the Sabarmati river and its tributary Bhogavo, in the Saurasthra region.

THINGS TO SEE AND DO

It is indeed hard to grasp what a crucial role Lothal has played in the history of the subcontinent, having connected the region to glorious and admittedly more popular civilizations westward, for instance Mesopotamia and Egypt.

Archaeologists have dated this site to as far back as 2450 BCE, with the Harappan period ending around 1900 BCE, transitioning into what is known as a Red Ware Culture in 1300 BCE.

The modest-sized settlement, as you will see as you walk around the ASI-protected area, was roughly rectangular in plan, surrounded by a wall that was initially made of mud and later of mud as well as burnt bricks. There was a burial ground in the northwest section of the settlement, outside the enclosing walls. The main citadel included an elevated area where you can now see remains of residential buildings, streets, lanes, bathing pavements and drains. Walk around the complex to admire the surviving walls of houses, as well as the fascinating drains.

Lothal would have been an important part of the Harappan civilization not only for its rich cotton and rice-growing areas, but also for its bead-making industry. The beads and semi-precious stones found in Lothal attest to a great level of artisanal skill, and many of these beads have been found in Mesopotamia, evidence of robust trade. Over time, a neatly planned township was constructed, a quintessential feature of the Mature Harappan phase, along with a dock for ships. Though only a small portion is now visible, the original town was divided into several block of one or two metre-high platforms made of sun-dried bricks. These platforms served as common plinths for a group of 20 to 30 houses, and a mud-brick wall of 13 m thickness gave protection against floods.

Some of the houses in the main area were quite large, with four to six rooms, bathrooms, a large courtyard and verandah.

The unique characteristic of urban Harappan settlements is in the division of the city into a citadel or ‘Upper Town’ and a ‘Lower Town’. It is assumed that social differentiation existed in Harappan society, and that the ruling class, whatever their nature and composition may have been, would have lived in the Upper Town, where the houses were built on 3-m high platforms and included paved bathing spaces, underground drains and a well for potable water

But the Lower Town was also equipped with crucial civic amenities, and in fact drainage and water facilities in the Harappan civilization are some of the stunning examples of early urbanisation in the Indian Subcontinent.

The streets were paved with mudbrick, with a layer of gravel on top. Houses belonging to artisans such as coppersmiths and beadmakers have been identified from the presence of kilns, raw materials and artefacts.

The most distinctive feature of Lothal is the dockyard, which is on the eastern edge of the site. The basin is enclosed by a wall of burnt bricks. The mechanisms of the dockyard are truly impressive for its time, with provisions for maintaining a regular level of water by means of a sluice gate and a spill channel. There is a mud-brick platform on the western embankment that may have been where goods would have been loaded and unloaded.

Lothal was a busy industrial centre that imported pure copper and produced artefacts such as bronze celts, chisels, spearheads and ornaments. Beads and shells of fine quality were produced primarily for trade and export purposes. Due to the area being flood prone, the town slowly shrank, ships stopped coming to the dock, and people eventually dispersed to nearby regions in what is called the Late Harappan period, which is characterised by an abandonment of the urban towns for smaller settlements.

At the foot of the mound at Lothal’s archaeological site remnants of the flood-damaged peripheral wall of mud-bricks can be seen near the corner of the warehouse. The warehouse possibly played the role of a storage house in the economy of the town. There may have originally been as many as 64 cubical blocks, but the many floods destroyed all but a few of the blocks even before the site was abandoned. Several clay labels that archaeologists found in this area confirm the view that the wood superstructure would have housed goods that were either being exported or imported. These sealings, some of which are on display in the site museum, are testament to the commercial nature of production of goods in Lothal, a crucial historical fact.

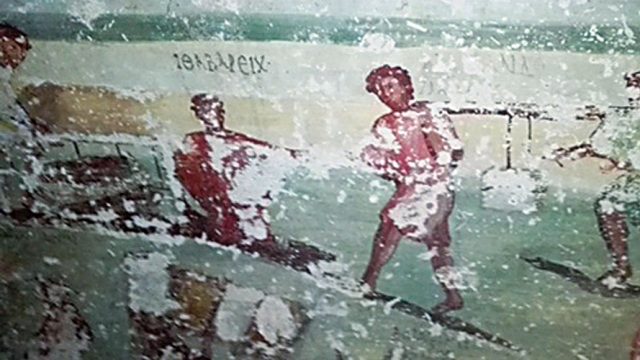

The archaeological museum in Lothal was set up in 1976, and it hosts a large display of some of the most striking artefacts found during the excavations. You can also look at archaeologists’ conjectural plans for the town, including the bead factory, and the original expanse of the dockyard. Displays include terracotta ornaments, beads, seal and sealing replicas, shell, ivory, copper and bronze objects, figurines representing animals and humans, gorgeous painted pottery, as well as fascinating objects recovered from burials in the cemetery site. One of the most fascinating finds in Lothal during excavation was a burial of two people together in a brick-lined grave; a replica of this can also be seen in the museum.

Museum Timings 10.00am-5.00pm, Closed Fridays

WHERE TO STAY AND EAT

A good place to stay while visiting Lothal is the Utelia Palace (Ahmedabad Tel: 079-26445770, 26763331, Cell: 09825012611; Tariff: ₹5,000-7,000), a heritage property in Utelia. It is about 4 km from Lothal heritage sites, enroute to Palitana, and offers 20 rooms and a restaurant. Meals cost extra (Breakfast – ₹450, lunch/ dinner – ₹750). The palace is closed during the summer months of May and June.

When to go October to March Location Close to the mouth of River Sabarmati, in eastern Gujarat Air Nearest airport: Ahmedabad Rail Nearest railhead: Ahmedabad

Gujarat

Harappan Culture

heritage