The way to my stomach is through my heart. And since I adore Banaras, it’s easy for

And yet, the magic of Banaras is that none of this seems like a paradox. Banarasi history is richly embedded with the most diverse of people and forces. It welcomed the enlightened Buddha as he crossed the river to teach his first sermon at Sarnath. It was native place to the seventh and 23rd Jain tirthankars. It saw the piety of Buddhist traveller Hieun Tsang. If Adi Sankaracharya came to begin strong Hindu monastic traditions, reformer Kabir, with his own brand of Banarasi masti quipped, “Going on endless pilgrimages, the world died, exhausted by so much bathing!” Tulsidas stayed on to battle the elite Sanskrit traditions by writing his Ramcharitmanas in the vernacular. Akbar facilitated the building of temples while Aurangzeb not only destroyed them but also named the city a futile ‘Muhammadabad’. Impressions of the city were recorded by western travellers, merchants, missionaries, administrators…. In the 18th century, attracted by the city’s sacred aura and secular vitality, Maratha, Bengali, Rajasthani and Bihari elites made the pukka ghats and the palaces and temples on them.

If you look, you can find some strand of all such traditions here. It’s not very surprising, then, that an Italian came to learn music, stayed for years, inducted his local friends into pizza making and inaugurated a pizzeria on the ghats, which continues even after he has left.

“Who would not live in Kashi where one can get both delicious food and liberation?” exclaimed Vyasa on being fed by Parvati in Kashi. A Banarsi old-timer and food expert links the food and the liberation for me. People came here to die, she says, pointing to a general acceptance of death as that which would bring moksha — freedom from the cycle of birth and death, and the attendant suffering. Once they accepted this, there was no need for the usual hurrying, doing, achieving, which are so much a part of life. Leisure was at hand. They could make an art of preparing the daily bread. “We had only seasonal vegetables. We had lots of digestives in chutneys and murabbas. We drank aam panna, chhachh or milk. People got together to not just eat but also cook — a leisurely process with gossip, a picnic ambience and the flavours coming together on slow dum chulhas.” I luxuriate in her offering of delicately flavoured khichdi at her home. “Khichdi ke chaar yaar,” she proclaims happily, “dahi, papad, ghee, achar.” But we also get to eat a mint and coriander chutney, a relish of radish pickled in mustard, papads made of not just dal but also of potatoes, curd-based papads…all employing an ease and comfort with ghee that has totally disappeared from metropolitan homes.

I taste similar flavours at that unique haveli-homestay called Ganges View at Assi Ghat, tastefully run by purane Banarsi par excellence, Shashank Singh. I say tasteful advisedly, having tasted the beyond-adjectives meals served here. They take the humble gobhi and dal and raise it to a fulsome fine art.

Out on the streets, however, I’m equally willing to consider the possibility that Parvati fed Vyasa kachori-subzi-jalebi in the old city. As you meander down the lanes that embrace the Vishwanath Mandir, you enter a lane actually called Kachori Gali. From about 8am to 11am, you get the proletarian’s or the pilgrim’s breakfast here. There are a couple of shops near the Gyanvapi entrance of the temple, and a number of pushcart-vendors near the Saraswati Phatak entrance. For Rs 10 you get a couple of khasta kachoris dipped in piping hot aloo-matar curry. The kachori, like a puri stuffed with ground dal and hing, is so crisp (khasta) it doesn’t melt in the mouth at all. You chew on it with contentment along with the cart puller, the shopkeeper and the devotee bracing himself to stand in the temple queue, following it up with a piece of voluptuously sweet jalebi. Nearby is the famous old sweetshop Shree Rajbandhu, where they show me their dry fruit creations made to look like litchis and mangoes. You must taste something, they say. Have a parwal-ki-mithai, that’s typically local, they say, refusing to accept payment for the rich and satisfying sweet.

At Thatheri Bazaar, near Chowk, a shop called Ram Bhandar specialises in kachoris and a vegetable curry to which they give an adventurous twist. As it is, Thatheri (utensil makers) Bazaar is a delightfully atmospheric lane in its own right. Narrow enclosures let you peep into huge pillared courtyards, there’s a house known for having held the oldest Durga Pujas outside Calcutta and there’s the house in which Bhartendu Harishchandra lived. Plenty of old fashioned vessels are still sold here. In the midst of which I join Sunday morning families waiting their turn for kachori fresh off the kadhai. The subzi here is an interesting mix of potato, badi (dried dal paste), chickpeas and a sweet-sour tang that dances on the tongue — they put a special chutney on the curry. Later, when I check a shop at Kabir Chaura I find they give the same curry with no chutney, a more sedate taste. And the well-known Vishwanath Mishthan Bhandar at Vishweshwar Ganj gives breakfast kachoris with a different subzi each day (“aloo, gobhi, or baingan…” they tell me, puzzled but polite).

The Ram Bhandar treat reaches a pinnacle when we walk on from Thatheri Bazaar to Chowkhamba. Here, in a narrow lane where a bull can cause a traffic jam, lots of people impatiently wait in front of a shoplet which is so legendary they didn’t bother with signboards. This is Markandeya, where they serve nimis, a name and concept that is disappearing from Banaras. For nimis, milk is boiled with saffron, pista and possibly a hint of sugar, till it thickens. It’s then left out at night — oh so poetically — in the dew. In the morning, a man churns up vast amounts of froth in the pot, scoops the weightless treat off to put in kulhars. A similar concoction is popularly sold as ‘malaiyyo’ but it’s heavier, may be sweetened and they put a lot of khoya on it — we purists scoff at it!

Markandeya is bang opposite the venerable Gopal Mandir (one of the eight seats of the Krishna deity at Nathdwara). It’s possibly due to this deity’s influence that the Vaishnava food culture of no-onion, no-garlic spread in the city of Shiva. The connection with Rajasthani Vaishnavism becomes transparent when we end up eating the Marwari thali at the Jaipuria Bhavan at Godaulia. This upper-end dharamshala was set up by a Seth Jaipuria and is run as a labour of love with profits going to charity. The food is cooked as bhog to the gods. The thali, redolent with ghee, has delicate kadhi, dal, vegetable and raita. They cook the slow way, on a wood stove, and have floor seating. My companion is not hungry but they can’t bear to see her not eating. Please have at least a papad, says one. Wait, I’ll get you a little meetha chawal, runs another.

In the evening, we traipse over to Deena Chaat (as Deenanath Keshari is popularly known) at Nariyal Gali, near Chowk. We survive a crowd of 50-odd devotees to corner some excellent aloo tikki (crisp and with dryish dahi), dahi-bada, a chuda-matar (like a poha delicately fried and with cashewnuts and raisin), golguppa that’s filled with chickpea paste and sweet yoghurt, and a brilliant spinach papdi-chaat for which alone I’m willing to make a trip to Banaras.

Our dinners are often a leisurely Continental or Mediterranean affair. This is almost entirely thanks to the foreigners who come to Banaras in the hippie, spiritual or yoga/music/language learning tradition. These touristy restaurants literally enjoy a back-to-back co-existence with the gastronomically ‘Indian’ Banaras. They face away from the ghats and, if far away enough, also serve non-veg. Of these, Phulwari Restaurant (Godaulia) and Hayat (behind Assi Ghat) have pretty much the same menu since they were begun by two Jordanian brothers, but Hayat offers non-veg and is a tad more expensive. Phulwari gives stuff like hummus or labannah, with pita, salad and chips, pastas, lasagna and moussaka. Hayat has more options, ranging from fried mutton with egg or grilled chicken/tuna sandwiches to main courses such as kubbeh (cous cous with mutton and herbs) or pizzas with capers and cheese. I loved the tahini and the fresh mocktails — great mojito with heightened ginger or Ya Habibi (vanilla ice cream and banana blended with hot chocolate and dry fruits).

At Bread of Life Bakery, on the main road parallel to Shivala Ghat, on successive days, we feast on breakfast (toast, eggs, hash browns, tomato, mushroom, coffee), pancakes with maple syrup and a wonderful quiche. Just a cappuccino with fresh cake or muffin here can make your day.

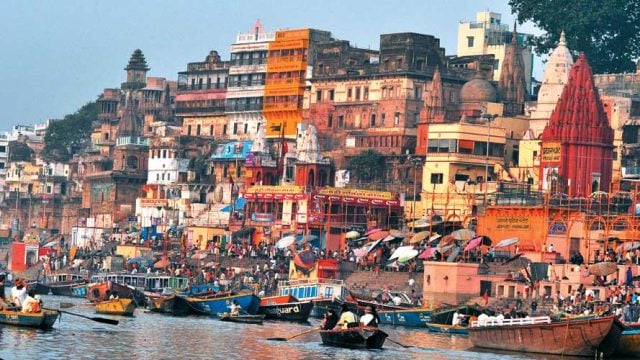

An excellent combo of location, food and price is the Pizzeria Vatika Café at Assi Ghat. Their crisp pizzas come with toppings like olives, pineapples, spinach and mushroom. One can sit here all day long and watch the Ganga, her boatmen, her recent acquisition of migratory seagulls. There’s always a breeze, always a bowl of leaves with marigolds, perhaps a boat with children selling toys. And we gently digest Banaras among what Mark Twain, who came here in 1826, called “the supreme showplace of Banaras… a splendid jumble of massive and picturesque masonry… movement, motion, human life everywhere…”

eating out

food guide

Varanasi

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.