I had been an incredibly untravelled guy until a whole series of fluke accidents sent me

In its aftermath, I spent three years in Cambridge, longing to get back to India, and satisfying myself by reading as much of travel writing as I could. I devoured all the great classics of travel writing, rigorously and comprehensively, because I knew that’s what I wanted to do eventually. Three books stood out at the time.

I wrote my first travel book, In Xanadu, when I was twenty-one, and it really is an amalgam of these three books—I didn’t find my own voice until my second and third books.

The first of these is my favourite travel book ever, and to my mind the greatest travel book ever written—The Road to Oxiana (1937), by Robert Byron, the story of a journey from Venice to Delhi. Robert Byron was a gay snobbish aesthete, a direct contemporary of Evelyn Waugh, Aldous Huxley, that whole generation of English writers. Byron was a really silly individual in many ways, but he wrote one outstanding masterpiece. It is to the travelogue what The Waste Land is to poetry, what Ulysses is to the novel.

He sets off on a steamer for Jerusalem, then crosses all the way round through Palestine, Syria, Lebanon, Iran and Afghanistan in 1933. He spent time in the 1920s with Edwin Lutyens, and his first great masterpiece of writing was describing Lutyens’ Delhi and the building of Rashtrapati Bhavan. It is one of the most descriptive writings about architecture in English. It is very much a product of its time; it is a book by a person who very unquestioningly accepts colonialism as an established fact of civilisation. The Road to Oxiana was a major model for me when I was writing In Xanadu, and in many ways my book is a pastiche of Robert Byron.

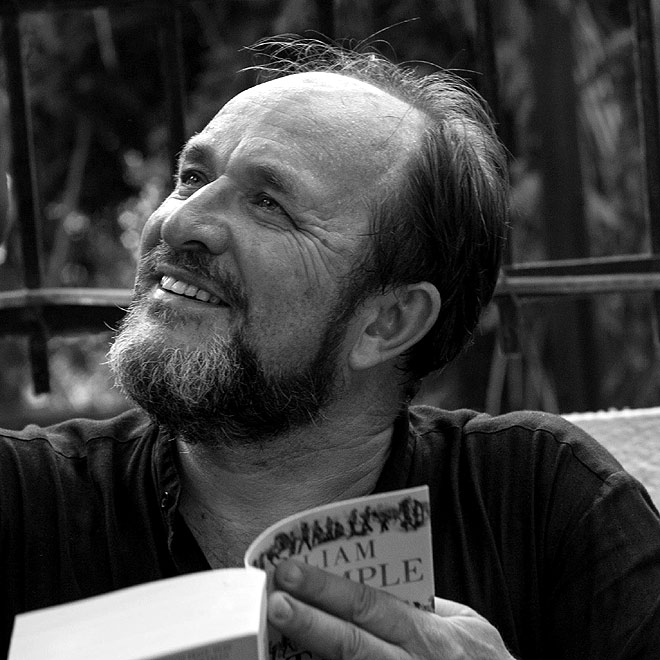

The second book is a journey taken almost in the same year, but was written up, bizarrely, some thirty years later—A Time of Gifts (1977), by Patrick Leigh Fermor. I met him when he was in his 70s, and he remained a firm friend until he passed away. He wrote great purple waterfalls of words—he over-wrote more brilliantly than anyone I’ve read since. He set off across Europe in 1933, and he arranged with his parents to send him ten pounds for every 500 miles. He picked this up along the way through Germany, Greece, all the way to Turkey, entirely on foot, with just one backpack. At the end of it, he has a coruscating affair with a Byzantine princess. They spent three idyllic years together. And in 1939, when he was harvesting in her fields, a horseman came with the news that Britain had declared war. The same afternoon he left on a horse to enlist.

He captured a German general and took him all the way to Alexandria—it was a great morale boost to the Allies. But then, having already been famous as a soldier, he became the greatest travel writer of his generation. At the end of the war, his girlfriend was stuck behind the Iron Curtain. He couldn’t get to see her again until 1977.

She was an older woman living in a one-bedroom flat in Bucharest and they talked night and day for ten days. She had had only one day to pack her belongings and leave for Bucharest, but she had managed to smuggle Paddy’s notebooks along. Partly as a tribute to his love for her, he then spent the rest of his life writing the story of his journey across Europe. It’s a very odd book, because it’s the story of an 18-year-old, written by an incredibly literate 55-year-old. It has the richest, most gorgeous prose.

The third book is at the opposite end of the pendulum. This is Bruce Chatwin’s In Patagonia (1977). It’s an extremely slim book, like a soufflé that you keep on the flames and reduce until it is very concentrated. It’s a masterpiece of prose and one of the best travel books ever written. It’s impossible to copy, one would sound ridiculous if one tried. I adored Chatwin, and I finally met him just as he was finishing The Songlines. He had already contracted AIDS, and he was quite soon to go mad and die in the most miserable fashion. But he was a shepherd and a guide, and I loved him. He’s the most brilliant author I’ve ever met. He was like a waterfall, he just talked and talked and talked and talked. And I was very sad when he passed away.