For someone whose reputation precedes him, Ved Mehta is refreshingly candid about the constraints of

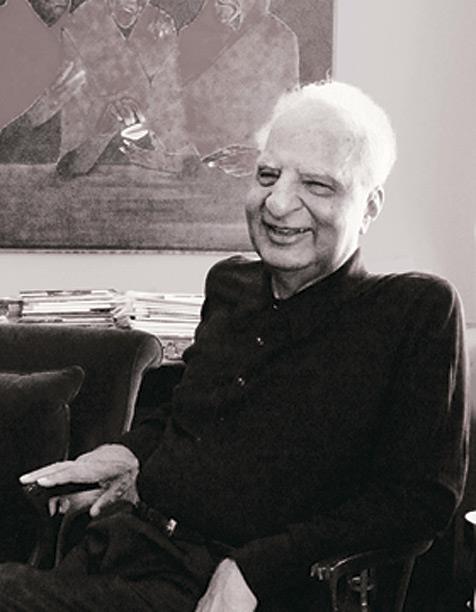

Such candour is the hallmark of Mehta’s writing and his personality. It is probably the defining factor of a life that he built for himself despite apparently insurmountable barriers. Sightless since he was a toddler, the Lahore-born Mehta was sent to a school for the blind in Bombay, but the institution was less a learning centre and more an orphanage. Now just past his 80th birthday, Mehta is a venerated name in international writing circles, with a few battle scars to prove his fighting spirit. He was in India earlier this year to launch The Essential Ved Mehta, an anthology of his writings over the years, culled from 25 previous books.

This very long journey was made possible only by Mehta’s dogged pursuit of a better future for himself, a resolve hidden by his mild-mannered social interactions. A blind young adult facing a bleak existence in the Indian subcontinent, Mehta wrote to any and every educational institution in America and Europe, requesting for a place as a student. After a stream of rejections, he was finally accepted by the Arkansas State School for the Blind.

“It was an exhilarating experience,” Mehta says of arriving in America in the early 1950s. He met Senator James William Fulbright, after whom the Fulbright scholarship was later named, and the Democrat leader had this advice to offer: “Don’t tell anyone you are an Indian, because no one knows what India is.”

That insularity was evident even in the city that shaped Ved Mehta as a writer. New York, a world city, “was a very provincial place” when he got there 64 years ago. Nevertheless, the city gave him two great gifts: an atmosphere of intellectual discussion, and the freedom to go everywhere alone.

Of all his travels — as the fledgling writer, then as a columnist for The New Yorker magazine, with which he was associated for 33 years, and then as an established, independent author — Mehta’s most memorable trip was to Oxford. He came to England to read modern history at Balliol College. The time was not long after India’s independence from British rule, and England existed in every Indian’s imagination, but it was still a revelation. “I had read about Oxford and the United Kingdom, but never had a clear impression of what this foreign country was,” he says of that first glimpse. “I’ve never forgotten any details [of the time] I arrived in the Queen’s kingdom. You could almost touch the kingdom.”

The tour of India, undertaken to research the book Portrait of India, was no less a revelation — with a few comic interludes. “Travelling gave me a great sense of the country. I was writing about R.K. Narayan, and going to Mysore was fascinating. I never knew that Madrasis say ‘wonly’ instead of ‘only’. And ‘yeggs’, not eggs. I tried to reproduce all that in my book.”

Westerners have a penchant for finding themselves in India. Would that apply to a person who was born in undivided India but remained isolated here and found his calling in the West? “I am still looking for myself,” says Mehta with a short laugh. “You have to lose yourself to find yourself. I think I am still hidden somewhere. You have to give yourself the entire experience to understand it.”

Though he says his writing is primarily done sitting in a chair, Mehta has travelled enough to have had some interesting encounters. At age 25, he met the Dalai Lama, also 25, when the latter had just fled China.

As two young men, he and the poet Dom Moraes, sat across a powerful Rana in a lavish palace then somewhat short of concubines, a situation caused by the 1951 revolution. In Walking the Indian Streets (1960), Mehta writes of this visit: “We are summoned to dinner. There are many other guests. The general welcomes us summarily, makes us feel that it is a great privilege even to be spoken to. We repeat our names many times, but he never gets them… During coffee, I corner the general to ask him about the revolution.

‘Wasn’t there a revolution in Nepal a few years back?’ I ask naively.

‘It was the time when I lost my hundred and fifty concubines,’ he answers.

New definition of revolution, I think. ‘What happened during the revolution?’

‘I lost my concubines.’

Before the revolution, a Rana could ride his elephant, and all the women in Kathmandu would crowd onto their balconies, eager for his attentions. If he waved at one, her fortune was made. She was taken into the palace. ‘No elephant rides now,’ he says. ‘The good old times are over. Now I have only seventy-eight maidservants.’”

“I meet so many people. Some very interesting people I have met for just five minutes. But I cannot afford the luxury of travelling and meeting people for the pleasure of it,” Mehta says, reminding us that he remains the quintessential ‘working’ writer. His wife, Linn Cary, accompanied him on some trips since their marriage in 1949, but most of Mehta’s journeys have been solo.

If there is one place he returns to again and again, it is India. And if there is one place he would not return to again, it is Pakistan. The memories of Partition — “ghosts” as he calls them — still haunt him. The modern state does not inspire much confidence either. “I would not like to go to Pakistan — I could get murdered,” Mehta says, not entirely as a joke.

He has lived through decades that have seen huge changes in the world. New York City has burgeoned from an almost small town to a megapolis. Mehta, who appreciates the fact that I conduct our interview in long hand, is not entirely comfortable with his city’s breakneck pace of transformation.

An example of this explosive change — albeit a positive one — is the food scene. In Mehta’s initial days, “there were only two Indian restaurants. One was the Ceylon India Inn, where the waiters always played card games.” Now, food from Hungary, Bulgaria, Russia and other countries has joined Indian cuisine, and these restaurants number in thousands, reflecting the diversity of the population. “There is a huge change in the US, and in the whole world, too,” muses Mehta. “Change is necessary, but not too much. Change is instability.” It certainly brings some practical difficulties, such as the city of one’s choice becoming increasingly unaffordable.

“I lived at first on East 58th St, and I have changed only six flats in 64 years,” he says of his time in New York. “It is very hard to find a good apartment, and when you do, it is not within your budget. But every time, I have discovered a new area.” We ask if he has heard of the micro-apartment trend in his city – flats that are about the width of a sofa-cum-bed and only marginally longer, practically a box in which one can just about stand up. “Must be hard making love standing up,” Mehta laughs again, flashing a sense of humour that 80 years have not dimmed.

He has embraced modernity by adding a computer to his usual packing list of razor, comb, toothbrush and paste. And there is another item he never forgets: “I always bring my head with me.”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.