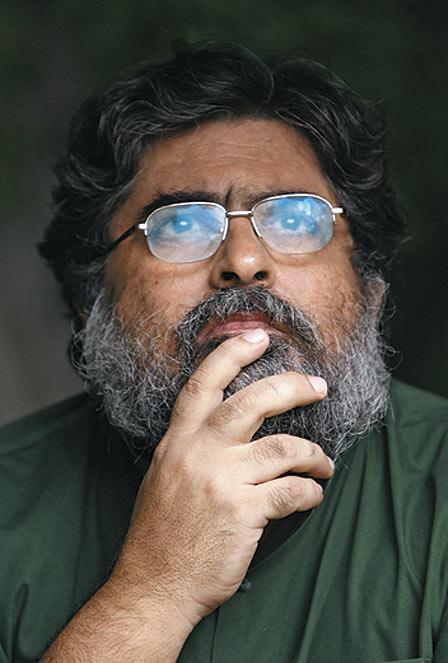

OT: Why tigers?

Valmik Thapar: My love for tigers started with my love for Ranthambhore. I

OT: And you’ve kept returning to Ranthambhore?

Valmik Thapar: Yes, of course. Ranthambhore has privileged me with experiences that I would never have thought possible — right from the start of the Project Tiger and the setting up of a sanctuary from scratch. It’s where we have found never-before pictures of tigers — fathers protecting cubs that we thought had been abandoned, a mother carrying cubs to another den and she does it so delicately, siblings helping each other remove porcupine quills after a hunt, young tigers fiddling about with everything they see, quite like we do when we are growing up — behaviours that added to our understanding of the tiger.

OT: What would you recall as your most extraordinary journey in the recent past?

Valmik Thapar: I went over a thousand books on tigers I had collected in nearly four decades but never read. It took me three years and sucked the mickey out of me. I didn’t think it would grow to be so gargantuan. Tiger Fire is a chiefly visual documentation of tigers for the last five hundred years, right from the time paper books were first printed in India. It was quite a trip.

OT: And what came out of it?

Valmik Thapar: We don’t have enough visual documentation of tigers because they are so difficult to film, which is what makes what we have so valuable. The portraitures, paintings and pencil drawings, including Mughal art, show how staged the royal hunts of medieval India were. The arrival of the British changed the narrative — the thick forests were treasures to be exploited for timber. The tiger was shown as an all-powerful beast and drawings of hand-to-hand combat with humans were common. But tigers in the wild are rarely encountered that easily.

OT: Your wildlife travels outside India?

Valmik Thapar: I go to Africa every year, to learn more from their wildlife management experiences. The bureaucracy in India is colonial, outdated and buffoonic. The Masai Mara [national reserve in Kenya] is not controlled by the government alone. The Masai keep grazing rights and villages partner in the management of the sanctuaries. Last year, funds we needed had to pass through 37 tables and chairs before they finally reached us six months later. Can you run and govern anything with this system? An 18-year-old planted 2,000 trees outside Ranthambore — give him the power to work in the sanctuary, don’t treat him like a nobody.

OT: Which would you call your favourite tiger sanctuaries in India outside of Ranthambore?

Valmik Thapar: Tadoba — a great deal of good work is happening there, especially under Shree Bhagwan, a forest officer who has brought about a lot of changes in the last ten years.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.