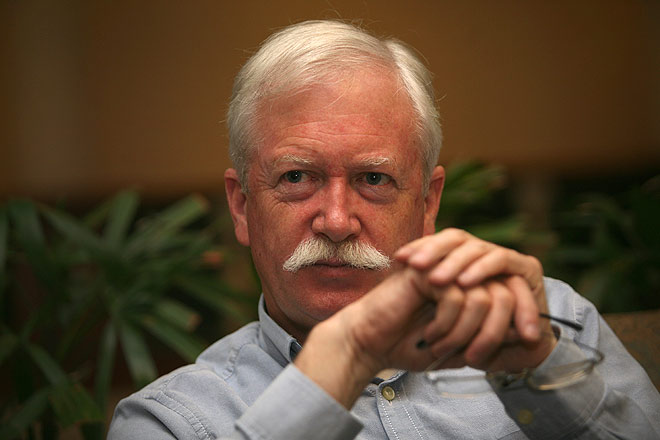

Stephen Alter wears many different hats with equal ease, that of an educator, a novelist and a

Outlook Traveller (OLT): When writing about nature, what’s your approach? Do you take notes when you’re in the outdoors?

Stephen Alter: Whatever I write about nature begins outdoors, through observations and encounters in mountains, forests or even in my backyard. Sometimes I take notes or photographs but often my initial impressions are simply the chance glimpses of a bird or animal that sparks my curiosity. The first thing to do is identify the species and then follow up with research so that I can tell its story and the stories of other species around it.

OLT: When you look at nature writing in India from a historical perspective, what’s the first thing that strikes you? Is there a common thread to how writers in India have viewed nature, through the ages?

Alter: Whether it’s the Rig Veda or Ruskin Bond, the common thread in nature writing is the diversity of creation that surrounds us. Many parts of India are ‘biodiversity hotspots’, where a multitude of species congregate in the same place. It is this richness that is so inspiring and also so easily threatened. Even if one plant or creature is removed from the mosaic, many others will disappear as well. Nature writing is part of a long tradition in India but contemporary nature writers are more aware of the potential for extinction and the consequences of such loss.

OLT: What is the absolute essential skill that any prospective nature writer should cultivate?

Alter: An ability to observe things through the eyes of a scientist and a poet, both at the same time.

OLT: You have been walking the Himalayan ranges for a while now, especially for Becoming a Mountain. What is it about the Himalaya that draw you there?

Alter: I was born in the mountains and they remain my home, so there is a particular sense of familiarity and belonging in the Himalayas. But it is also the magnitude that inspires me, the elevation and breadth of the Himalaya. At the same time, I often find that what catches my eye are the smaller elements at the side of the path—a flower or butterfly that is as much a part of the mountains as myself.

OLT: Nature writers have always grappled with the definition of ‘wild’ and ‘wilderness’. The poet Gary Snyder says that the words ‘free’, ‘spontaneous’, ‘sustainable’ and ‘non-exploitative’ might be an apt way to define it. What has your experience taught you?

Alter: ‘Wild’ is one of those words that confuses us because it has so many definitions. But in its best sense, ‘wild’ refers to those places where human beings have not left their mark. Poets like Gary Snyder inspire us to explore wild places without desecrating the natural sanctity of those environments. This isn’t easy and we often fail but I like to think of ‘wildness’ also as a state of mind, when we can become a part of the wilderness without intruding upon it.

OLT: How do you feel about India’s wilderness today? Is it under greater pressure?

Alter: India’s population continues to grow and there are very few places that we can call a true wilderness in India. Instead of all this nonsense about ‘eco-friendly’ solutions or ‘green-initiatives’, there should be certain places in India where we do nothing at all, except allow the area to be untouched by man. Imagine 1,000 acres that is closed off to man for a 1,000 years. That is the sort of place that should be preserved and protected, both as an idea and in reality.

OLT: What do you suppose increasingly urbanised human beings need to do to discover their own ‘wildness’?

Alter: If we can imagine a wilderness, we can also discover it in small places. A cluster of flowerpots on a terrace in Mumbai can be a symbol of distant and inaccessible wild places. The birds in the trees outside a city apartment might fly off to a wilderness area tomorrow. They can connect us to somewhere we cannot go ourselves.