It’s probably just brain damage caused by the rarefied air, but the brown mountains around

Like many people, I had no idea that there had ever been a kingdom in Ladakh, let alone that it still exists. I had a protocol crisis. What was I to call the present king — Your Highness? Mr King? “We call him Jigi,” said an acquaintance of his unhelpfully. The traditional Ladakhi title is Gyalpo. To my eternal disgrace I ended up calling him, “Er, hello”.

“I’m a casual person,” said H.E. Raja Jigmed Wangchuk Namgyal (his proper title), reclining on a divan at his home in the 180-yearold Stok Palace and picking at pistachios, pine nuts and raisins. True: he’s 47, bespectacled, with grey hair and rosy cheeks, dressed in a fleece jacket and cords — a professorial look. The room glistened with old golden thread and paint and wood; across the river lay the rocky knuckles of Shey and Thiksey monasteries. “The world is very different today. I’m comfortable with anything people call me.”

Raja Jigmed Namgyal is the 38th ruler in a line going back to the late 900s, when King Skyid-lde Nyi-ma mGon (descended from the first king of Tibet, who himself descended from heaven on a cord in about 200 BC) conquered the chieftains of the area and established himself as the first Ladakhi king — all with 300 horsemen on a diet of eggs and fish. His successor, Lha-Chen dPalgyi-mGon, built a palace at Shey.

Royal Relics near Leh

The Stok Palace Museum shelters a fantastic collection. Apart from the 1,000-year-old crowns, you will find the queen’s perag (an ornamental strip of leather worn on the head), encrusted with 401 lumps of uncut turquoise. There are gold and silver teapots; pearl, coral and turquoise jewellery; and 35 ancient thangkas telling the Buddha’s story. You’ll also see wooden blocks used to print prayer flags, and drums and trumpets made of human bone for use in tantric rituals. In one of the treasure-filled rooms is a sword whose blade has been twisted into a knot, like putty. It was mangled by an oracle during a festival, years ago, to prove his powers when he sensed the presence of a sceptic in the crowd.

It was locked, but I panted up the hill to Shey Monastery, to see its fabulous old murals: snarling images of Mahakal on a lotus, engulfed in flames; oblique-eyed apsaras; and a portrait that I imagine must be the king’s. They surround the blue-eyed stare of the two-storey, gilt-copper image of the Shakyamuni Buddha added by Gyalpo Deldan Namgyal in the 17th century. The bluff dominates Shey village below, littered with chortens. From here the kings did their bit for Buddhism, empire, and general rosiness. By the end of the 13th century, so the songs say, “people became so rich that they wore hats of gold, and their mouths never became empty of tea and beer”.

On a rock below is an ancient carving of the Maitreya Buddha. In the village I stopped by the mosque built for Gyal Khatun, the spunky 16th-century princess from Baltistan who married King Jamyang Namgyal, of whom more later — but it looks spanking new and unimpressive, and I couldn’t read the Urdu inscription. The rheumy-eyed imam cast dark aspersions on the whole idea of history (“Who knows what the story is… Nobody in Ladakh went even to Srinagar… They say praying here will grant your heart’s desire… Who knows…”).

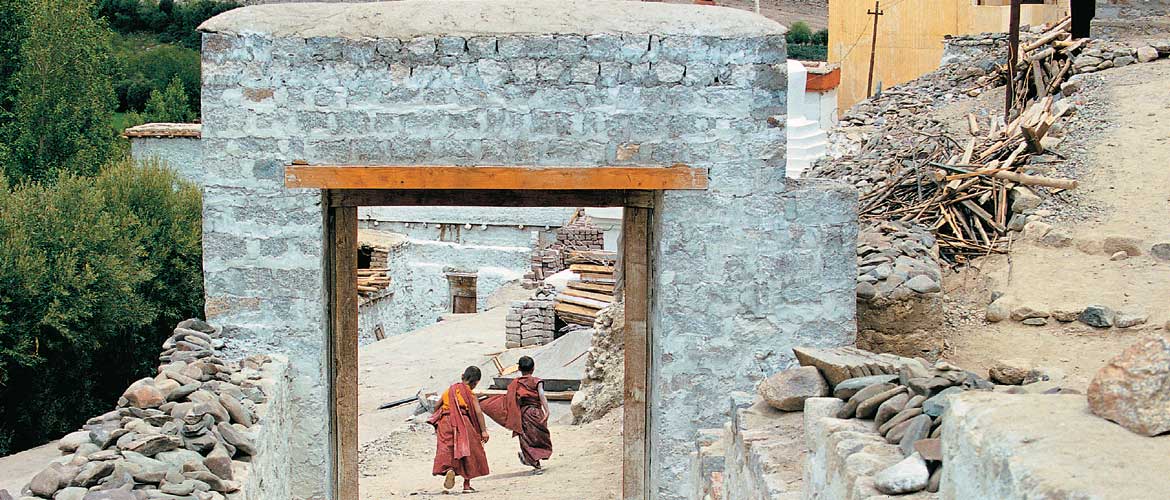

I went to Matho monastery, famous for its yearly oracle festival. Nearing the promontory tucked away between snowcaps, driving past scores of chortens in the village, you can feel the pull of old and wise magic. I was pacing the courtyard, listening to the silence and the breeze, when two monks appeared. In the early 15th century, they said, the Tibetan lama Dorje Palsang chose a cave at Matho in which to meditate. At the time, the king Drags-pa Bum-Ide needed to consecrate a stupa to contain a fire-breathing demon which lived at Tisseru, and was causing great misfortune. “The lama flew across the river to Leh and consecrated the stupa,” the monks told me, “and the king gave him this land to build his monastery.” To date, the oracles of the 700-year-old protectors, Rongsten Kar Mar, meditate in a small room nearby.

In the little monastery museum I took in murals, masks, scriptures, clothes, and odds-and-ends. Matho Gompa’s strongly Tibetan tradition is a result of the monarchy’s decision, in the 14th century, to send all novices to Tibet. From that point on, Lhasa became the beacon for Ladakhi Buddhism. The chronicles of Ladakh, La-dvags rGyal-rabs, even ignore prince Lha-Chen rGyal-bu Rin-Chem because, after a disagreement with his father, he stamped off to Kashmir and converted to Islam.

Start of the Namgyal line

The capital of Ladakh moved to Basgo in 1645, where it remained for 200 years; meanwhile, in 1470 AD, Ba-rGan deposed his father and founded the Namgyal (‘perfect victor’) dynasty. It was to produce both the greatest of Ladakhi kings as well as — as Dr Luciano Petech grumpily observed in his Study on the Chronicles of Ladakh — “mean and sometimes even despicable characters”. On a bluff commanding the valley, Basgo’s crumbling fortifications belie its past glory. Its highest point is given to a two-storey Maitreya Buddha; below the palace lie the Ser-zangs temple and the Chamchung shrine.

If I hadn’t already been breathless from trudging up steps, the 16th-century murals in the Maitreya temple would have knocked the wind out of me. These delicate paintings, coloured with crushed stone, were added by Tsewang Namgyal. “We had to deconsecrate the temple to start work,” conservationist Sanjay Dhar told me. “They hold a mirror up to the deity to capture its spirit, then they wrap up the mirror to preserve the spirit until it’s released back into the figure.” It was the pretty town of Basgo, filled with streams, willows and apricot trees, that took the lead in preserving what is now a World Heritage Site.

On the second floor of the Serzangs temple I came eyeball to eyeball with the enormous Buddha, built in King Jamyang Namgyal’s time and encrusted with huge lumps of turquoise, wearing a turquoise and coral necklace said to be that of Gyal Khatun. The villagers have reassembled the scattered pages of a copy of the Kangyur written in gold script on paper darkened with lampblack, and there is a gilt silver shrine donated by Gyal Khatun, and an image of the goddess Palden Lhamo.

No dynasty worth its salt is short on treachery and back-stabbing. In the 16th century, the heir to the throne was blinded and deposed by his younger brother, Tashi Namgyal. Tashi’s conscience had the grace to trouble him, and he built the beautiful Phyang monastery. Tashi also built Tsemo Namgyal, the first palace to crown Leh’s windy ridges. Its fortifications are in ruins, but two temples — one of Avalokitesvara and one of the Four Lords — shelter sooty murals which you should get on a plane at once to see. I goggled at them and at the figures, whose faces are covered until they are used in festivals. Outside, the wind curled around prayer flags. Below me lay the later nine-storeyed palace; Leh sprawled even lower, and to the right rose the large dusty smudge of the Tisseru chorten.

Natural justice prevailed: Tashi could not have children, and had to marry off his blind brother to beget some nephews to succeed him. The eldest of these, Tsewang Namgyal, made a great name for himself, before his brother, Jamyang Namgyal, almost lost it all in a disastrous campaign against Baltistan. Ali Mir, the wily chief of Skardu, swept into Ladakh and burned all the books he could find, then rubbed the king’s nose in the dirt by reinstating him in exchange for marrying his daughter Gyal Khatun, disinheriting the two children from his first marriage and accepting the suzerainty of Skardu.

The ‘Lion’ Namgyal

It was a bitter pill to swallow, but an injection of plucky Balti blood revitalised the family stock. Gyal Khatun’s son, the lion-hearted Sengye Namgyal (1590-1640), grew to be the greatest king of Ladakh. Father Francisco de Azeveda, a Portuguese priest who visited Ladakh, described him as tall and brown, “something of the Javanese in his features”, with shoulder-length hair, turquoise and coral earrings, and a string of skull bones around his neck. He built the nine-storied palace at Leh.

Sengye Namgyal conquered Zanskar, and built the great monastery at Hemis, in a secluded cleft in the mountains — now just a picturesque drive away. When his son Deldan died, the kingdom was at its largest, having swallowed Purang-Guge, including the area between the Maryum La and Lake Mansarovar, Rudok, Spiti and upper Kinnaur; upper Lahaul, Zanskar, and the lower Shayok Valley. But Deldan’s son, Delegs Namgyal, interfered in a religious quarrel with Lhasa and found the Tibeto-Mongol army snapping at the doors of Basgo, which settled in for its epic siege in 1679-1680. Delegs took to his heels, and in return for Mughal assistance signed all kinds of unhappy agreements, renamed himself Aqibat Mahmud Khan, and built Leh’s Jama Masjid. I think he tried to redeem himself by making it look a bit Ladakhi, but architecture won’t blunt the facts.

From then on things nosedived. It was left to the quite eccentric Tsephal Namgyal, who often required 13 basins of cold and hot water to wash his hands, to build the charming palace at Stok in the 1820s, said to be “one dress colder” than at Leh. He was no hurdle for the Dogra army of Zorawar Singh, who finally annexed Ladakh to J&K in 1841. Raja Jigmed Namgyal is the most recent occupant of Stok Palace, where the royal family was packed off. “I’m privileged and honoured to have been born into this family,” he said. “I want my contribution to be a revival of Ladakhi interest in Ladakhi culture and tradition. I want to get the community involved in their heritage.”

He changed into his handsome black choba with a yellow sash, and dutifully climbed to the palace terrace to be photographed — a king who knows his limitations, and has carved a meaningful space for himself. After him his son, Stanzin Jigmed Namgyal, will wear the 1,000-year-old Ladakhi crown. I looked at him standing in the last glow of dusk in the whipping wind, a lone form, curiously forlorn against those muscular Zanskar mountains, and I thought I could see the spirits of all his ancestors hovering around him.

Royal Resources

To learn more about Ladakhi history, the NGO of the present king, Namgyal Institute for Research on Ladakhi Art and Culture (NIRLAC; Shangara House, Tukcha Main, Leh) has a library in Delhi (B-25, Qutab Institutional Area), which is a good resource on Ladakh. In Ladakh itself, the Central Institute of Buddhist Studies (Tel: 01982-264387, Web: cibs.ac.in) at Choglamsar, Leh and the J&K Cultural Academy (jkculture.nic.in) sub offices in Leh (Ladakh Cultural Academy Complex, near Mini Secretariat and Petrol Pump, Tel: 01982-252088) and Kargil (Baroo, Kargil; Tel: 01985-232096) are also good resources

India

Ladakh

heritage