In the past 102 years, since Dadasaheb Phalke made Raja Harishchandra, the first silent feature

The ‘40s, ‘50s and ‘60s gave Hindi cinema some of its most memorable classics: Awaara (1951), Kaagaz Ke Phool (1959), Mughal-e- Azam (1957), Sahib Bibi Aur Ghulam (1962) and Guide (1965). Playback singers such as Mukesh, Mohd. Rafi, Kishore Kumar, Hemant Kumar, Talat Mehmood, Manna Dey, Lata Mangeshkar, Geeta Dutt, Asha Bhosle and Shamshad Begum rose to fame. It also led to the creation of the star system. Dev Anand, Dilip Kumar and Raj Kapoor were idolised, as were Madhubala, Nargis, Waheeda Rehman and Vyjayantimala. As studios became more powerful and Bollywood grew more commercialised, there arose a movement that would later be called Parallel Cinema.

- Bollywood Features – Rewinding The Reel

The Parallel Cinema movement originated in Bengal in the ‘50s and soon made its way to Bollywood. The films of this movement were more realistic, compared to the larger-than-life portrayals of commercial Bollywood films; they mostly rejected the elaborate song and dance numbers that typified mainstream cinema; and focused on the sociopolitical climate of the times. The movement gave birth to directors such as Satyajit Ray, Mrinal Sen, Bimal Roy and Khwaja Ahmed Abbas who would go on to gain international acclaim. Roy brought the movement’s main themes to Hindi cinema with Do Bigha Zamin (1953). The film, which tells the story of a farmer desperate to save his land, received critical and commercial success, and won the International Prize at the 1954 Cannes Film Festival.

Seeds of such thought had already been seen in Chetan Anand’s Neecha Nagar (1943) but it was in the ‘60s that the movement gained steam. Parallel Cinema thrived but as a steady political situation brought more hope to the citizens, the movement evolved to better reflect the changing social realities. This new genre was dubbed as ‘middle-of-the-road’ cinema as it merged the ideology of Parallel Cinema with the commercial aspects of mainstream Bollywood, thereby creating movies that told slice-of-life stories focusing on the middle-class. The pioneers of this movement included Hrishikesh Mukherjee, Basu Chatterjee and Gulzar.

In the late ‘60s and ‘70s, movies which cemented the importance of this movement included Mukherjee’s Satyakam (1968), Anand (1970), Guddi (1971), Bawarchi (1972), Abhimaan and Namak Haraam (1973), Chupke Chupke and Mili (1975) and Gol Maal (1979); Chatterjee’s Piya Ka Ghar (1972), Rajnigandha (1974), Chitchor and Chhoti Si Baat (1976); and Gulzar’s Koshish, Parichay and Achanak (1972), Mausam, Khushboo and Aandhi (1975) and Kinara (1977).

While both Parallel and Middle-of- the-Road Cinema enjoyed commercial success, they did not take away from mainstream cinema’s popularity. As the movements gave rise to stars such as Sanjeev Kumar, Jaya Bhaduri, Utpal Dutt and Amol Palekar, mainstream cinema had filmmakers Yash Chopra, Prakash Mehra, Shakti Samanta and Manmohan Desai; actresses Mumtaz, Rekha, Hema Malini, Zeenat Aman and Rakhee; and ‘the phenomenon’ Rajesh Khanna. He played the quintessential romantic hero in movies such as Aradhana and Do Raaste (1969), Safar (1970), Mehboob Ki Mehndi (1971), Amar Prem (1972), Daag (1973) and Roti (1974). He also featured in Mukherjee’s Middle-of-the-Road cinematic endeavours, Anand (1971) and Namak Haram (1973). With his films setting cash registers ringing, and fans writing him love letters in blood and marrying his photographs, he overtook Rajendra ‘Jubilee’ Kumar and came to be known as Hindi cinema’s ‘first superstar’.

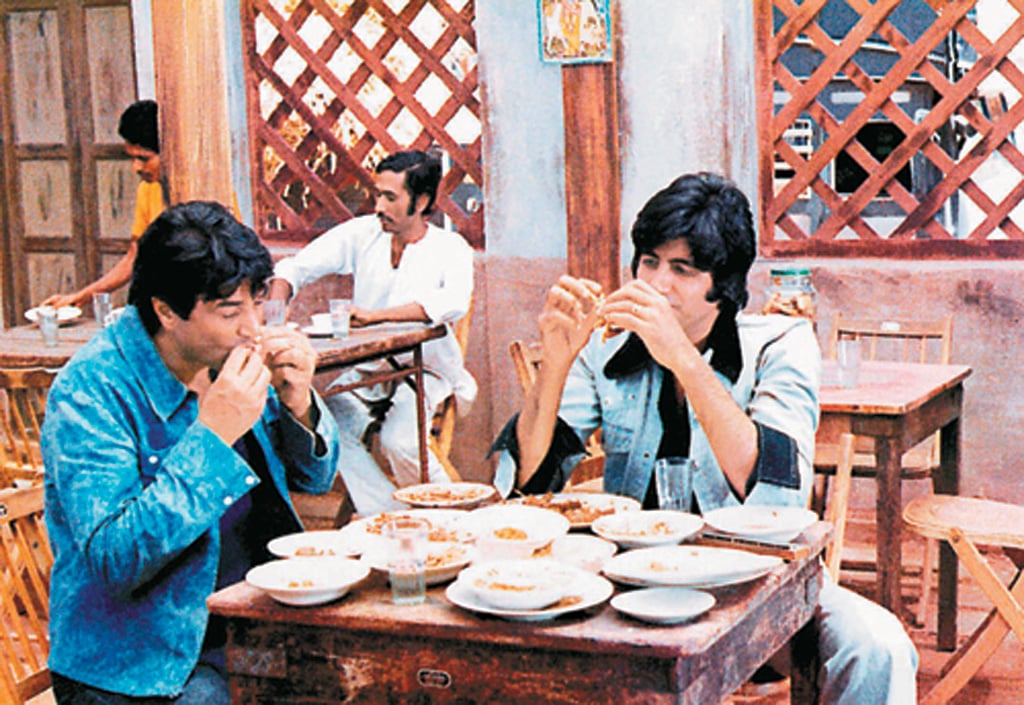

With the sociopolitical situation undergoing drastic change, thanks to the Emergency of 1975, there emerged a new character, and with him, a new superstar. In movies such as Zanjeer (1973), Deewaar (1975), Trishul (1978) and Kaala Patthar (1979), writers Salim Khan and Javed Akhtar created a character, who fought against everything that’s wrong with the Establishment, and was later dubbed ‘the Angry Young Man’. The actor who portrayed this Everyman’s various incarnations was Amitabh Bachchan. With these movies, and others such as Abhimaan (1973), Sholay (1975), Kabhi Kabhie (1976), Amar Akbar Anthony (1977), and Don and Muqaddar Ka Sikandar (1978), he cemented his position as the leading actor of Bollywood.

Mainstream Bollywood hit a new low in the ‘80s: the plots were mediocre, the songs uninspiring and dialogues forgettable. Yet, the decade also gave birth to stars such as Mithun Chakraborty, Jackie Shroff, Anil Kapoor, Sunny Deol, Meenakshi Seshadri, Sridevi and Madhuri Dixit. Few movies of this period are memorable: Disco Dancer (1982), Hero (1983), Betaab (1983), Mr. India (1987), Tezaab (1988) and Ram Lakhan (1989). The struggles of the common man took forefront as Parallel Cinema thrived with Naseeruddin Shah, Farooque Shaikh, Shabana Azmi and Smita Patil featuring in acclaimed films such as Sai Paranjpe’s Sparsh (1980), Chashme Buddoor (1981) and Katha (1983), Mahesh Bhatt’s Arth (1982), Shyam Benegal’s Mandi, Kundan Shah’s Jaane Bhi Do Yaaro and Govind Nihalani’s Ardh Satya (1983), and Ketan Mehta’s Mirch Masala (1987).

- Stills from Sholay

- Stills from Dabangg

The Indian economy opened up post-globalisation in the ‘90s and Bollywood finally got official industry status in 1998. These were reflected in the movies’ thematic and technical changes. Visual effects came into play; films told stories about the diaspora and were shot in exotic locations – from the Swiss Alps to the pyramids of Egypt. New stars rose to fame with the Khan triumvirate – Shahrukh, Aamir and Salman – ruling the box-office. Lagaan (2001) was nominated in the Best Foreign Language Film category at the 74th Academy Awards in 2002. Commercial Cinema nudged out Parallel Cinema and sat firmly in the hearts of the audience.

Today, Bollywood boasts of employing action directors and editors from Hollywood; movies that cross the Rs. 200-crore earnings mark in a week with screenings in the US, the UK and even Nigeria; and award shows where the likes of John Travolta shake a leg. Irfan Khan, Anil Kapoor and Priyanka Chopra are making inroads in American movies and TV shows. As a young, eager India finds a space for herself on the international platform, the Hindi film industry too has become truly global.

Film City: Behind the Scenes

The bus rumbles along a narrow lane, surrounded by lush greenery. The tour guide explains that the road has led to Lucknow and Jaipur, as needed, by installing the relevant milestones. A video plays on the bus’s TV screen showing Amitabh Bachchan walking on (ostensibly) the same road while trekking to Vaishnodevi temple in Kohram and freedom fighters marching in 1942-A Love Story. The guide then points to the surroundings, saying “This area has doubled up as a jungle in many movies and TV shows.”

The official Film City tour, organised by the Maharashtra Tourism Development Corporation and so-called even though the government renamed the attraction Dadasaheb Phalke Chitranagari way back in 2001, is a locations-only tour. Any sighting of celebrities is strictly coincidental.

The locations are not very enthralling. There is a Josh Maidan, where the eponymous Shahrukh Khan-Aishwarya Rai-starrer and Bajirao Mastani were shot. No set stands there now; it’s just a barren piece of land, waiting for someone to make it beautiful again. Farishtey Maidan has a set but it’s hidden behind high walls, but you can get a good look at Maharana Pratap’s palace from the TV show.

The trip has three highlights – a temple, a helipad and a housing society – where you can get down from the bus and take photos. First is the helipad, a patch of brown overlooking a shallow cliff. It was here that Salman Khan, Fardeen Khan and Anil Kapoor hung from a rock in the climax of No Entry.

Then there’s the white-and-gold temple. It is a permanent structure but the idol varies from movie to movie. Strike a pose at the spot where Shahrukh Khan and Rani Mukherjee prayed in Kuch Kuch Hota Hai. The third highlight, which is the last stop on the tour, is the façade of the homes and shops in and around Gokuldham Co-operative Housing Society. This is strictly for fans of Taarak Mehta Ka Oolta Chashmah.

Two-hour guided tour costs ₹599 per person above the age of five; includes a 500 ml water bottle and a small snack.

Film City

Hindi Film Industry

Maharashtra Guide