You cannot hope to travel light on the train to Tibet: there’s just way too

Mao Zedong dreamt of building this line, of using it as an instrument in the pacification of China’s Wild West. “If the railway isn’t built,” he is believed to have said, “I can’t ever fall asleep.” Thirty years after Mao slipped the surly bonds of earth and shuffled off into eternal sleep, his dream has come true.

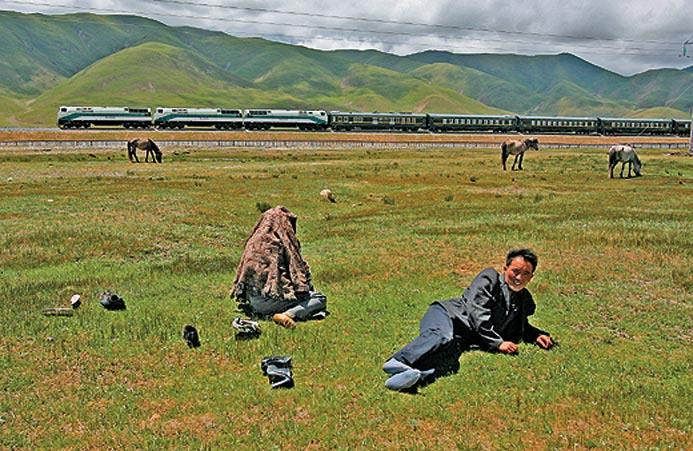

Today, that locomotive dream thunders across spectacular landscapes, ferrying some 4,000 passengers each day into the glittering Lhasa station. Only the final leg of the railway line—from Golmud to Lhasa, a distance of about 1,140km—is new, having been inaugurated in July this year; the lines up to Golmud had been completed in various phases over the past few decades. This last stretch, built between 2001 and 2005 at a cost of $4 billion, traverses through the most breathtaking (literally, given the rarefied atmosphere) terrain where the altitude varies between 4,000m and 5,100m. Nearly half of that new stretch is built on permafrost: frozen subsoil that some say is already showing symptoms of glacial impermanence.

These are truly audacious feats of engineering: even Paul Theroux, who wrote that the railway line to Tibet could never be built (and argued that, as a concession to Tibetan spiritual purity, it should never be), would conceivably have marvelled at the sheer engineering efficiency of it all.

But enough about metal and mechanics: the train journey is about more than just these mundane matters……

I boarded the train at Lanzhou, the capital of Gansu province, at 4.45pm. The city, which is at the geographical heart of China, was once an important stop on the Silk Road and a key garrison post; today, it is a polluted industrial town that’s best known for its beef noodles. It’s also one of the seven cities of origin of the train to Tibet, the others being Beijing, Shanghai, Chongqing, Chengdu (in Sichuan province), Xining (in Qinghai) and Guangzhou (in Guangdong).

A cheery attendant led me to the soft-sleeper cabin that I would share, for the next thirty hours, with a Chinese family of three: a thirty-year-old schoolteacher from Xi’an was treating her parents to a holiday in Lhasa. Without any marked dimunition in her cheeriness, the attendant informed me that a septuagenarian man had recently died on board the train owing to complications arising from altitude sickness. Her manner, as she made me sign a health declaration form, appeared to suggest that I too should be a good sport and do something equally dramatic to help break the tedium of her journey.

My initial attempts at breaking the ice with my travelling companions weren’t crowned with success. I considered breaking into song—Raj Kapoor-era films tunes are a particular favourite with the Chinese—but abandoned this entente endeavour in favour of a walkabout of the train. Outside the double-glazed, UV-filtered windows, it was beginning to get dark, and in any case the best views could be had only on the morrow. Besides, I’d learnt that the dining car was well-stocked with Budweiser beer, and a live kitchen was cranking out a carnivorous carnival of dishes……

The soft-sleeper cabin compartments (as opposed to the hard-sleeper and the hard seat compartments) provide superior travelling comfort. But they come with the minor annoyance of flat-screen TVs that beam endless rounds of a propagandist film on the railway line construction; the Chinese, ever given to hyperbolic turns of phrase, call the train “The Steel Dragon that Flies Across the Sky”. But back in cattle class, where passengers were crammed ninety-eight to a compartment and the eco-friendly squat-toilets were rather more odoriferous, I rather suspect they’d have given an arm just to get a bit more elbow-room.

At dinner, as the train rolled noiselessly through the Qinghai plateau, I found myself thrown together with three boisterous Chinese engineers who exhibited an infinite capacity to quaff Budweiser’s barley delights. At 3,500m, and given the low oxygen level, the alcoholic effect gets amplified; in their case, it manifested itself in a marked ebullition of animal spirits. Every time a raucous guffaw went up, a Tibetan family, eating silently and mindfully across the aisle, looked up nervously and appeared to shrink.

The next morning, I woke up to an enchanting sunrise on the Gobi Desert fringe, and tumbled out of the train when it pulled into Golmud. Out on the platform, in the chill dawn air, elderly Chinese women were performing tai chi routines, their septuagenarian limbs sweeping graceful arcs as they ‘Parted the Mane of the Wild Horse’ or ‘Carried the Tiger and Returned to the Mountain’.

At the head of the train, more powerful engines were being hooked up in preparation for the steep climb ahead. Chinese linesmen, their faces red with exertion, toiled away, clinically supervised by stern-faced officers in military regalia.

From Golmud, the air gets so thin that with every breath you take, you’re sucking in only about half as much oxygen as you do at sea level, and to pre-empt an outbreak of altitude sickness, oxygen is pumped into the cabins. Even so, some infirm passengers complained of headache or breathed hard and reached for the oxygen tubes.

Altitude sickness is a decidedly rotten thing to happen; it puts you in no frame of mind to enjoy the ethereal beauty outside. Fat, fluffy clouds floating in bluest-blue skies caressed snow-capped peaks; rivers gushed through stark lunar landscapes; truck drivers on the winding road alongside the tracks waved energetically; the occasional chiru, or the endangered Tibetan antelope, darted away from the steel dragon roaring across the sky……

Inside the train, too, there was plenty of action. Budweiser flowed plentifully in the dining car. A handful of nicotine junkies surreptitiously dragged away on forbidden cigarettes, at the risk of blowing up the oxygen-rich train. Two gloriously wrinkled men waged battle across a Chinese chessboard, to the accompaniment of hoots and laughter from onlookers. A succession of camera clicks announced the advance of an army of amateur photographers. And the constant buzz of mobile phones on board bore testimony to another uniquely Chinese infrastructural engineering marvel: signal strength didn’t drop even a notch on the twenty-nine-hour journey.

In the afternoon, at 2.45pm, a thrill of excitement pulsed through the train as we clambered onto the Roof of the World and touched the face of god. Tangu La Pass is, at 5,072m, the highest point on the plateau, and in some ways the high point of the journey. Passengers posed for photographs beneath the live tickers on board the train, which flash the time, the speed of the train, and the altitude in three languages: English, Chinese and Tibetan.

The high excitement of that moment—and perhaps the wooziness that comes from too much booze—appeared to take its toll on some fellow-passengers. Many of them curled up and dozed off for the remainder of the journey. A hush descended on the train, as it rolled downhill all the way to Lhasa.

The reason why thousands of tourists come every year to Tibet is, of course, to experience a living, breathing godly civilisation that still retains an element of spiritual purity owing, in large part, to its geographical isolation. To arrive, as I did, by one of the marvels of modern mechanical engineering to catch a glimpse of this pre-industrial—and perhaps pre-historic— place does, admittedly, create a curious dissonance of the mind. I feel like I’ve stepped off a time machine into a beautiful past. That mind-bend only gets accentuated as I head out of the post-modern train station and into the streets of Lhasa and make for Jokhang Square, where the ebb of time is marked by the slow whirl of countless prayer wheels…

For schedules, frequency and fares of trains to Lhasa, visit chinatibettrain.com.

railway

Roof of the world

Tibet