Camel ride, sir?Great camel.”

“Nahin ji.”

“Why nahin ji, sir?” What could I say? There’s

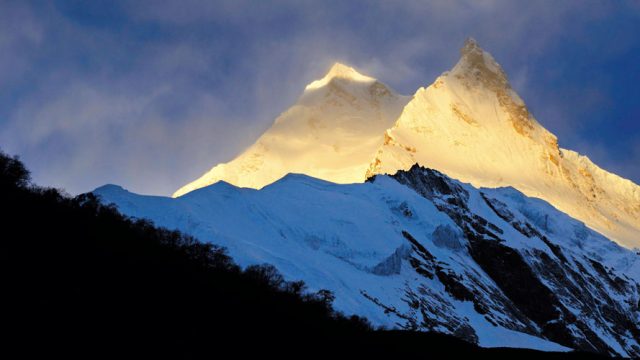

I had never been to Pushkar before, and at the risk of sounding gauche, I have to admit that nothing had prepared me for this. Despite being one of India’s prime tourist magnets, Pushkar feels strangely isolated. This may be purely geographic —the town is situated in a valley between parallel rows of the Aravali range, cut off from its larger neighbour, Ajmer, and indeed from the rest of the world. The Aravali are, of course, far older than the Himalaya, and it is fascinating to imagine how these mountains must have looked in the depths of deep geological time. Secluded in the desert, the town of Pushkar and its cosmic lake are indeed timeless.

This is in part due to a self-reinforcing alliance between the medieval architecture of the town and an even older religio-cultural tradition. Pushkar has to be one of the oldest holy towns in India, second only to Varanasi. Yet it’s different too. Brahma is worshipped here, as is well known, but his wives also get their due. The Brahmin Savitri and the tribal Gayatri, both boon-granting goddesses, occupy two prominent hilltop shrines on either side of the lake, keeping a watchful eye on their husband. Even in the context of the pantheon, this is Hinduism at its most basic: Brahma and the holy cow—rather, the cow’s purifying mouth—get the two main ghats by Pushkar lake.

The 52 whitewashed ghats rise up from the lake in that familiar cluster of layered balconies, chattris and terraces that is common to many old pilgrim towns. These provide enough nooks and crannies for bathers to preserve their modesty, or for the bahurupiya to don his make-up, while he transforms into Hanuman or Shiva.

Photography is understandably banned here, considering the number of people in states of casual nudity as they dip themselves repeatedly in the lake’s sacred waters. Every day brings more anxious pilgrims, clutching single carry-bags, the women with the ends of their saris firmly tucked into their mouth, and looking for a dharamshala to stay. Of these there are plenty, some of which specify caste affiliations, providing their patrons ‘full service’—lodging, food and ease of worship. When the waxing moon reaches its zenith on the night of Kartik Purnima, in a re-enactment of Brahma’s mythical yagna attended by all the gods of the pantheon, thousands of people from around the country jostle here for just that one, cathartic dip in the lake’s sacred waters.

It’s easy to see how the intensity of an exotic faith and the sheer physical splendour of a landscape can combine to such effect on a jaded, urban mind. But while many come here in search of the ineffable, others are here for more tangible reasons. I’ve been noticing a young man in a keffiyeh all day, wandering about town, his sharp eyes darting; his bulging arsenal of lenses on the ready to capture the colourful and the serendipitous. I finally corner him at one of the large dining tents for camel-herders, while he’s shoving his camera into the impressive moustache of a peanut vendor. His name is Vikram, and he’s from Mumbai.

“Are you here on an assignment?”

“No man, I’m here to shoot my portfolio.”

“Portfolio?”

“Yeah, man. Your portfolio is incomplete without Pushkar. Look around, man, isn’t it great?”

Yes it is, I agree, and he lopes off towards the makeshift tent city that sprouts up every year outside town. It houses the camels, horses and cows, as well as their grooms, minders and sellers. It’s carnival time for the local tribal people; busily chewing sugarcane, buying farm implements, hukkas and kitchen utensils while an army of photographers shadow their every move, shooting 15 frames a second. If you discount the camels and the holy city vibe, Pushkar is curiously like Santiniketan’s Poush Mela—essentially an annual local fair that politely ignores its well-heeled city patrons.

In another category are the ‘Pushkarites’—decidedly more urban than their nomadic brethren—who go about their day in the cheerful knowledge that it’s one long holiday. When the slanting sun paints everything gold late in the afternoon, they emerge in their finery to ride the ferris wheels, eat whatever junk they can get their hands on, visit the temples and the ghats and generally have a good time. However, to many jaded Pushkar hands, there aren’t any real ‘Pushkarites’, just nomads and tourists.

The serious business is transacted at the camel fair. The camel is to the Rajasthani nomad what the yak is to a Tibetan—a support system, a source of sustenance as well as a principal mode of transport. So buying a good camel makes everyone happy. Everywhere I stop for a cup of tea or a smoke, there’s invariably a gaggle of wiry, weather-beaten men in dusty white shirts and large colourful pagdis conspiratorially discussing camels. And in this regard, the notorious Rajasthani preference for all things male seems to fall through. “A female camel or a male, what difference does it make, really? I want a good camel,” admonishes a bidi-smoking elder to a harried flunkey, who rushes off to seal the deal.

But if camels constitute the bulk of the business, horses fetch the higher prices. Pushkar Mela is the place to buy and sell thoroughbreds, especially the Sindhi and Marwari varieties. The horse enclosures are usually peopled by minor Rajput potentates or their agents dressed sharply in riding breeches, jodhpurs and sporting royal crests on their stylish jeeps. A hub for race and polo horses, some desirable animals can fetch really high prices, going up to Rs 5 lakh. Mohar Singh of Kherla village was busy brushing the coat of his dashing brown horse, Badal. Is it true, I asked him, that a horse had sold the previous day for Rs 95 lakh? He hadn’t heard of such a thing, but he asked me to beware of the sellers of non-Marwari horses. They were spreading misinformation. What did Badal cost? He studied my face a full five seconds and said, “Rs 4 lakh.”

Later as I walked towards the car park, in the bright light of the waxing moon, I thrilled to the mystical charge of an almost-full moon in this oasis under eldritch stars, surrounded by hills over 200 million years old. Who knows, maybe on Kartik Purnima the Old Ones themselves might descend. Pushkar would probably take it in its stride.

cattle fair

festivals

India