Agra must be one of the most scorned cities in India — it would seem that because

In short, there is much to see in Agra beyond the big four tourist sites and I spent many days during 2006 exploring it. I have found that the best way to get to know cities is simply to walk and walk, constructing a map as I go. Local guides can help you home in on the well-known buildings but there is nothing like serendipity for finding lesser-known places.

I would arrive by train from Delhi and even before I set off I would look for buildings — I was excited to glimpse the four white minarets of the gateway to Akbar’s Tomb and, closer to the railway line, the boundary wall of a handsome tomb, traditionally believed to be that of Jahangir’s mother. A little further on I spotted two very decayed tombs; now used to house buffaloes and fodder, but once surely the handsome tombs of courtiers grand enough to be buried in proximity to the great Emperor himself. But the real fun began when I set off from the station on foot. This was generally Raja ki Mandi station, where the Taj Express conveniently makes a stop.

My first foray took me to the Civil Lines, the area of the city outskirts that was first developed by the British. I enjoyed walking round this part of Agra, which is full of contrasts, revealing the different ways in which the city was Europeanised. For instance, the well-kept Roman Catholic cemetery evokes the pre-colonial period when the Europeans here were adventurers — mercenaries or traders — and sometimes saw themselves and their families as ‘Indian’, albeit with a European background, and built their tombs accordingly. By contrast, the court system evokes real colonialism par excellence; coming from a legal family in the UK I am always intrigued by glimpses of the court system in India and I enjoyed watching the bustle among the old Civil Court buildings opposite the cemetery.

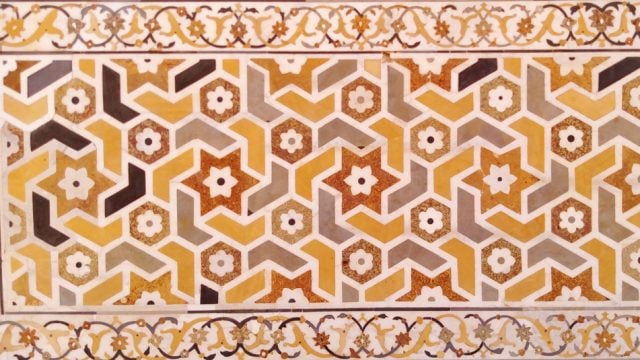

There are numerous reminders in Agra of how the Indian elite adapted themselves to the colonial lifestyle. For instance, southwest of the Civil Courts area there was once a grand tomb (built for Shah Jahan’s first wife, Kandahari Begum) surrounded by a high wall with corner turrets and pavilions. The tomb itself collapsed a long time ago and in its place the Maharaja of Bharatpur built himself a large house with a curious lozenge-shaped plan. Although I mourn the loss of fine bits of architecture I also enjoy the way that old buildings can be adapted for reuse, sometimes saving them from total destruction. This old enclosure wall would no doubt have vanished with the tomb if it had not become the garden wall of a rich man’s house. Another side of colonialism — education and the church — imprinted itself firmly in the large area now dominated by the fine Roman Catholic Cathedral. I was bewildered by the number of schools clustered here, especially as my visit coincided with the end of the school day, so there were children everywhere in their different uniforms. The school buildings are of various dates and are generally handsome, but the importance of the site is attested to by the charming (so-called) Akbar’s Church. Although history tells us that Shah Jahan had the original church torn down, a replacement was built in 1772, with a more recent extension following at the front. When I wandered up someone immediately went to fetch the keys and let me in to see the interior. Otherwise very European, it is unusual in having exotic late-Mughal panels fixed low on the nave walls.

The colonial areas of Agra were built in the interstices of existing urban areas, which had been contained within a city wall built in the 1720s. As well as the area that can be identified as the original ‘old city’ there were numerous ‘suburbs’, often old market areas, and these are very easy to identify with their narrow streets and traditional buildings. My favourite ‘suburb’ is Lohamandi, near Raja ki Mandi station. It is a quiet residential area, divided by the railway line in one direction and an intensely busy bazaar street in the other. On my first exploration I came away with the impression of narrow streets lined with a mixture of pleasant houses, none of them particularly old but many built with great craftsmanship; the old parts of Agra are replete with exquisitely carved doorways, often overhung by balconies prettily screened in stone, wood or metal. Later I found my way down the principal streets to two of the old city gates which, together with the line of the 1720s wall, still mark a clear distinction between the high density but self-respecting older urban area and the rather chaotic mixture of colonial roads and informal settlements outside it. A rewarding find in the middle of Lohamandi was the Mangleshwar temple, a serene enclosure full of small shrines and, nearby, a large and handsome (dry) tank with curious ornate gateways, one of which has a charming doggerel inscription, part of which goes:

At Agra his place of learning

Good means of subsistence earning

Viz English Arabic Urdoo

Persian Sanskrit Hindoo too

The tank is not far from Agra College, a famous local ‘place of learning’, and one of several colonial educational establishments strung out along MG Road. This is not the most attractive road to walk on, but I enjoyed visiting the campuses of both Agra College and St John’s College (north on MG Rd), St John’s for its grand Indo-Saracenic architecture and Agra College for its rather more welcoming Gothic. Here a friendly member of staff pointed out to me the oldest building, at the back of the site. South of Agra College one can find another old suburban area, Nai ki Mandi, along the rather forbiddingly straight and narrow Ghalibpura Road. My main object here was to locate the famous sinking mosque of Shah Alauddin Mujzub (part of a dargah that also goes by other names). From the attractive centre of Nai ki Mandi I encircled the area in one direction, wending my way through a network of residential lanes, in one of which I found what must have been an outlying dargah building, now stranded outside the enclosure. Failing to find the dargah itself I went back and approached from the other side until I came to a gateway through which I could see activity and the telltale sight of vendors selling trinkets to dargah visitors. The mosque is indeed as intriguing as all the accounts avow: only the very tops of the columns show above the ground so that people have to stoop beneath the entrance arches, and yet the surrounding buildings stand proud on the surface.

In my explorations of Agra my biggest challenge was getting to know the old city area. Unlike other cities Mughal Agra did not have solid walls, although it probably had a ditch and gateways that defined the perimeter of the city. In my wanderings I covered the whole of this area plus some of the areas where the city spilled out beyond the original ‘gates’, which happened most obviously along the riverfront, where beautiful gardens once lined the river for kilometres. I found great contrasts, for instance, between the heaving main streets — Kinari Bazaar, Rawat Pada and Kashmiri Bazaar — and the tranquil residential lanes off them. Then there were contrasts between neighbourhoods such as that between the area near the Jama Masjid, where narrow lanes wind in and out of the steep gullies that were created in the easily eroded soil of Agra, and the flatter areas near the river where old gardens survived into the 19th century and were then redeveloped in a more spacious way. I was intrigued by some of the very fine houses that had clearly been built inside one such garden, now known as Suraj Bhan Phatak, that were so beautiful and yet so neglected, some even looking abandoned. A particularly exciting ‘discovery’ was the decaying façade of a huge building built opposite and in alignment with the most extravagant of the non-imperial city mosques, Motamid Khan Masjid — could this have been the main entrance to a haveli belonging to Motamid Khan, the interior now reduced to a single street with no other access? Or might it have been his garden? There is ample scope in this city for detailed research.

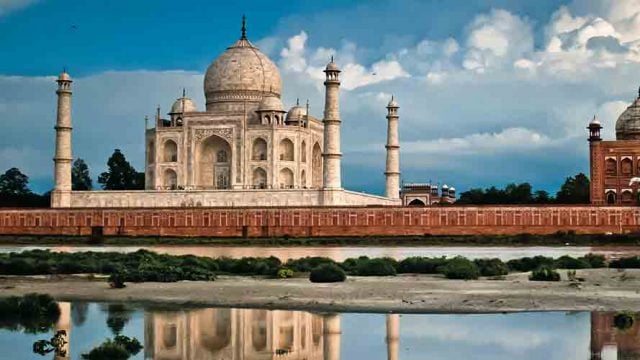

As a contrast to the intricate complexity of the urban areas it was enjoyable to cross the river and explore the remains of the Mughal gardens. There are more relics than people are generally aware of. Solitary corner turrets, ruined pavilions and tombs can be glimpsed from across the river but exploring on foot brings surprises. I followed the riverbank all the way from the grand Battis Khamba north of Ram Bagh to near the tomb of Itmad-ud-Daula and a particular delight was wandering in the remains of the garden once owned by Mumtaz Mahal before it was passed to her daughter Jahanara. Only one double-storey turret and some crumbling brickwork remain from the riverfront buildings but behind them one can wander among the luxuriant greenery of the garden plots, now horticultural nurseries but still divided by the original raised pathways, which are now used to channel irrigation water pumped from the river.

I hope this account will inspire people to strike out and find many of the little-known gems of this under-rated city, of which only a few are mentioned here. I cannot pretend that ugliness and squalor are absent, but I found it well worth ignoring these and other inconveniences for the interest of knowing Agra better.

The information

Getting there

BY ROAD Agra is 205km/3hr by road from Delhi. BY RAIL The Bhopal Shatabdi (leaves Delhi 6.15am, arrives 8.15am; Rs 370 on CC) only stops at Agra Cant. — good for visiting the Taj Mahal but less so for the rest of the city. The Taj Express (leaves 7.10am, arrives 9.50am; Rs 262 on CC) takes longer but stops at Raja ki Mandi, closer to Akbar’s Tomb, the old city and the riverside gardens.

Where to stay

At the very top end is the Amar Vilas (0562-2231515, www.amarvilas.com) — rooms from about Rs 30,000! Also five-star but more affordable is the ITC Mughal (from Rs 12,000; 2331701, www.itcwelcomgroup.in), which has a luscious new spa that’s perfect for between-monument-seeing breaks. There’s also the Taj View Hotel (from Rs 3,000; 2232400, www.tajhotels. com), the Trident (from Rs 3,500; 2331818; www.tridenthotels.com) and Jaypee Palace (from Rs 8,000; 2330800, www.jaypeehotels.com). Budget options include Hotel Sheela (Rs 400-800; 2333074; www.hotelsheela agra.com) and the Tourist Rest House on Kutcheri Road (Rs 300-850; 2363961).

The monuments

> The Civil Lines area lies between Raja ki Mandi and NH2 — the Roman Catholic cemetery is near the flyover where NH2 crosses the main MG-Dayal Bagh Road. Kandahari Bagh is on Raja Balwant Singh Road. Akbar’s Church and the Roman Catholic Cathedral are east of the hideous Sanjay Place. Lohamandi, St John’s College, Agra College and Nai ki Mandi are all accessible from MG Road. Take the narrow road between the Labchand Market buildings for Lohamandi. The two colleges are conspicuous from the road.

For the Dargah of Shah Alauddin Mujzub take the road that goes east at a noticeable bend in MG Rd. A lane running north from this road, about a hundred yards from the junction, ends at the gate of the Dargah.

> The old city can be approached from the Raja ki Mandi area or by taking the busy road under the railway line near the Delhi Gate of the Red Fort. Bear right and then cross a busy road to the back of the Jama Masjid. An attractive lane opposite the northwest tower of the mosque is a possible starting point for an exploration of the old streets. The road/rail bridge that connects the old city to the other side of the river starts not far from Suraj Bhan Phatak, off Sekhsaria Road, which runs between Belangunj and the river. Motamid Khan’s Mosque is just off Kashmiri Bazaar.

> The ruined Mughal gardens are all found north of the tomb of Itmad-ud-Daula. Jahanara’s garden lies just to the north of the tomb known as Chini ka Rauza and can be approached from the lane that leads to the tomb or alternatively from Aligarh Road, down a dirt road that leads to a small settlement in the garden.

Agra beyond Taj Mahal

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.