Bas thodi si charhai hai, ji (there’s only a little bit of climbing). Each time a pahadi

We had just begun our hike in the upper reaches of the Ravi catchment in Chamba, Himachal Pradesh. Our plan was to pass through forests, fields and fruit orchards between six and eight thousand feet, stopping at forest resthouses for the night. It sounded delightful, yet when the first uphill climb hit, my main emotion was dismay. But we were now off the road and the only way out was to go on and up. So I huffed and puffed and got on with it. And tried to believe our guide Sunil Kumar when he said that the next day’s walk would be all “parallel-parallel” (since Sunil is a pahadi, of course it turned out to be anything but).

We had spent the night in the Deula resthouse, one of the many dotting Himachal’s forests. Several of these resthouses were built in the 1920s and 1930s when Chamba was a princely state. Apparently, ‘raja ke time pe’ forest officers were a more energetic lot, touring the remoter regions on foot and horseback and staying overnight to supervise timber felling and planting, settle villagers’ claims, and keep their subordinate staff on their toes. Since then, things have gone a bit downhill. Senior officers rarely visit the off-road Chamba resthouses and some of them look decidedly decrepit. Yet their shabbiness has its own charm. Placed on picturesque sites, with the snowy Dhauladhar and Pir Panjal ranges looming over vast valley panoramas, their bare boards and rustic fare seem completely in sync with their surroundings.

At Deula, dusk had brought a sharp fall in temperature. The electricity was temporarily out and the stars were brilliant. I duly checked out Cassiopeia and Perseus and took my shivering self to the fire in the cook-hut, helping the chowkidar string some beans for our supper, sipping hot smoky chai. The chai was soon followed by hearty dal, sabzi and hot rotis puffed up on the embers, simple and delicious. A whisky nightcap on the verandah and then blissfully to sleep under a thick quilt.

We left the resthouse early in the morning and climbed steeply up into a forest with gigantic trees of deodar and oak, horse-chestnut and spruce. Moss, fungi and ferns covered huge fallen logs; the air was moist and cool, filled with birdcalls, and fecund with things growing and decaying. As we rested on a rock, a sunbeam broke through the trees and shone on a scarlet minivet swaying on the top of a deodar. I quickly panned the binoculars and, sure enough, there was a party of these dazzling orange and yellow birds flying from tree to tree, moving down the valley. I have unsophisticated birding tastes — the brighter the better — and nothing beats minivets for sheer Technicolor splendour.

We met a shepherd in the forest, his woollen coat and trousers carefully darned and patched, gold rings gleaming in his ears. While his sheep and goats browsed through the under-storey, he strolled along, his hands busy spinning yarn on a small spindle. Later, we came across another flock of silky-haired goats and sheep sunning themselves beside a stream, waiting their turn to be shorn of their wool. The man with the shears would grab a sheep and, tucking its head firmly under his arm, start shaving its belly. The sheep seemed bemused but happy with the whole affair, even though the haircut left them looking bald and quite silly.

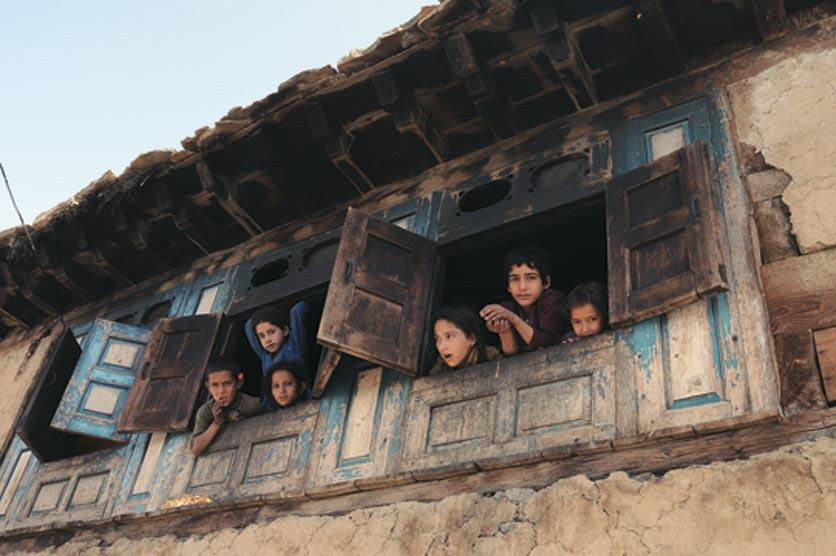

October is the season in Chamba for shearing wool and for stocking up firewood for the snowy winter months. In the fields, the maize crop was being brought in, the dry stalks and leaves saved for fodder. From a distance, each village blazed a brilliant golden orange as every flat roof was covered with drying corncobs. Every time we stopped at a village, a couple of freshly roasted bhuttas would arrive. Once we got small velvety peaches, juicy and green. Snacks like these were a bonus; spending the time of day with villagers chatting in the sun or warming ourselves by a kitchen fire was a gentle pleasure by itself, each conversation a glimpse into a world very different from ours.

The villages in these parts of Chamba are fairly well-to-do. Their livestock, fields, forest and fruit trees give them enough in cash and kind to live comfortably through the year. Many of the men we met had worked outside Himachal Pradesh, but were now content making a living at home. After the mandatory questions about marital status and number of children, the conversation would invariably turn to City Life versus Village Life, and the superiority of the latter. But in some ways, rural Himachal has the best of both worlds. Schools and health services work in the remotest villages. The roads are good. And everyone, including the shepherd, has a mobile phone.

Even when we were on top of a ridge, far away from habitation, someone’s phone would suddenly start ringing. There’s nothing like a jazzy ring-tone to bring all fantasies of being in the middle of nowhere crashing down to earth. But there were moments on our hike when we were out of signal range and that has now become my benchmark for wilderness — the place beyond the reach of Reliance, Airtel and Vodafone. When we were high up in a forest of pure deodar, even the cellphones were silenced. The air was crisp, the forest floor clean of all except bracken. It was a complete contrast from the palpably living, breathing deciduous forest we’d passed below, yet beautiful in its own antiseptic way.

Descending from the deodars, we came to the tiny Saloh forest resthouse, with its nursery of deodar, walnut and robinia saplings. The resthouse commanded a spectacular view but had no water, furniture or kitchen, so we stayed in the village below. In the evening, we came back up to watch the sunset, sit around a crackling bonfire and listen to the chowkidar’s tale about the two leopards that ate three villagers the previous year. (They shot one and the other was trapped with a dog as bait.)

The next day was the killer walk to Chhatri, 16km of allegedly ‘parallel-parallel’. Far too much of it was a hot tramp along hillsides exposed to the sun. If it hadn’t been for the porter explaining the finer points of ganja-making as we passed plants twice as tall as ourselves, it would have been a dull walk, indeed. Just as I was getting a bit fed up, we dropped down into a bed of a beautiful Himalayan stream, the Baira. The water rushed by deliciously cold and it was a joy to take shoes off and paddle among the rocks. Then up again, zigzagging through forest and fields, stopping to watch a long-legged buzzard glide past on the thermals, banking and soaring with effortless grace.

By the time we reached Chhatri, the sky was overcast and a chill wind had sprung up. After walking for six hours, we were tired, hungry and cold. The chowkidar busied himself and soon we were tucking into rajma, lightly-cooked sarson ka saag and makki ki roti — the beans, mustard greens and corn all freshly harvested from the fields below. Believe me, everything they say about local seeds and organic farming is absolutely true: the food tasted fantastic. The chowkidar had kindled a couple of small logs in our fireplace and soon after I snuggled under the quilt, I fell fast asleep.

The next day, we dawdled in the sunshine, lazily listening to the liquid warble of bulbuls (three different kinds) flitting among the fig, wild pear and oak trees. Then it was time for the final leg of our hike, down, down to the Baira, following the stream to Kalhel. As we left the forest, we were suddenly surrounded by groves of wild olives. With the autumn sun on their silvery leaves, it was as if we had been transported to northern Italy. There were steep cliffs of ochre stone with waterfalls gushing down into the stream below. We passed an abandoned watermill and a cremation — flowing water performs so many functions. With a sinking heart, we read the signboards for yet more hydro-power projects. Soon, every tributary of the Ravi and Beas will be dammed many times over. Even the so-called ‘run of the river’ projects destroy rivers forever. I looked at the elegant little white-capped water redstart briskly wagging its tail, waiting to snap up an insect from the water, and drank in the perfection of the stream. It will be gone before too long.

The information

The walk

Deula Forest Resthouse to Saloh Forest Resthouse is a 9km hike through mixed deciduous forest. Though the Saloh Forest Resthouse is uninhabitable, a night’s stay and meals can be arranged in the village. From Saloh to Chhatri Forest Resthouse is a 16km walk through villages and open scrub, crossing two streams. From Chhatri to Kalhel Forest Resthouse is a 9km walk through fields and village forests, and the last 4km are on the road.

Other forest resthouse walks

The Himachal Pradesh forest department is promoting a few other forest resthouse circuits. The Rohru circuit in the Shimla Forest Circle takes you to the resthouses at Kashdhar, Larot, Dodra, Kawar, Jiskoon and Jakha. There’s a lot of birding to be done on the trek, and you can also go river rafting in the Pabbar. The Nogli-Taklech-Daranghati circuit in the Rampur Forest Circle includes the resthouses at Nogli, Taklech and Gopalpur. The Bilaspur eco-circuit in the Bilaspur Forest Circle goes from the resthouse at Naina Devi to Bandhla to Bahadurpur and finally to Gwalthai. Most of these involve easy to moderately difficult treks. For more, see www.hpforest.nic.in.

Contact

Staying in a forest resthouse requires a permit issued by the Divisional Forest Officer in Chamba (01899-222239). For tourists, the charges are Rs 200-400 per room per day. Breakfast, lunch and dinner for three people costs about Rs 150-250. Mani Mahesh Tours charges Rs 500 a day for a guide, and Rs 300 for a porter. It is also possible to hire a local as a guide-cum-porter at the resthouses.

Kalatop

We had to drive a long way from our forest trail to visit the pride of Chamba’s Forest Resthouses. Ten kilometres above Dalhousie sits the Kalatop Forest Resthouse, surrounded by deodar forests in the Kalatop Wildlife Sanctuary, reputedly home to the Himalayan Black Bear. Built in 1925 and maintained in tip-top condition, the Kalatop Forest Resthouse is the perfect hilltop bungalow, with green lawns and flowerbeds looking out at views of the Dhauladhar range. From the forest resthouse, one can hike up to a designated look-out point; however, the view to be obtained is a bit of a let-down, consisting mainly of an enormous satellite dish, reportedly Asia’s second biggest radar. Kalatop is 86km by road from Pathankot.

Chhatri

Dhauladhar range

Forest Resthouses