Full confession: I’m not a ‘mountains person’. Maybe it’s because I spent the better part

So what was I doing sitting in a car bound for alpine Binsar, perched at 8,000 feet in the Kumaon Himalaya? At the outset, just doing my job. Binsar is essentially a wildlife sanctuary and, in the heart of it, a new luxury property, Mary Budden Estate, had just begun to welcome its first guests. “Once you’re there, it’s beautiful,” I was repeatedly assured. But first, there was an 11-hour drive to endure.

We left Delhi before sunup, passing fields of mustard and open countryside sporadically obscured by a veil of fog that escorted us all the way to Kathgodam, before suddenly abandoning us under bright skies and sunshine. The hills had arrived. For anyone travelling right now, however, the climb to Binsar isn’t going to be simple. At Khairna, soon after you negotiate the bustle at Bhimtal, appears a road that falls precipitously down to a parched riverbed and continues its precarious haul for twenty-two kilometres. The rains had clearly been cruel this year. We pushed higher, past congested Almora, to a complete change of scenery as concrete gave way to a sprawling splash of green.

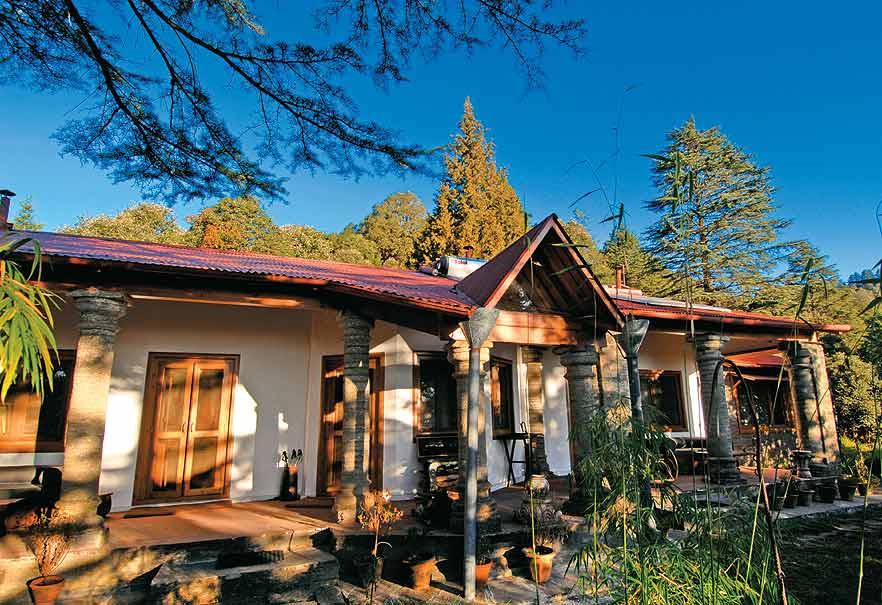

Mary Budden Estate is just how you might picture an English country cottage: a quaint stone-walled façade displaying a hint of flowering creeper, timber flooring within, cosy fireplaces and bukharis in every room, snug sofas, cheerful kilims, a brass bell to ring for the staff, fat white duvets to burrow into… Outside, oak-laden slopes and terraced lawns scattered with wicker furniture. They were right. It was beautiful and the journey instantly forgotten.

As with most places, there is history here too. The five-acre space was once the home of Mary Budden, an English missionary. A fragile, yellowing document that stands framed in the living room shows that Budden had acquired the place in 1899 from a General McGregor. Somewhere down the line it fell into the hands of one Mr Bhandari, who preserved it exactly the way Budden had left it, till he decided to sell it in 1990 to its current owners, Serena and Ashwani Chopra. For about nineteen years, it stayed a ramshackle house, serving as a getaway for the Chopras whenever they needed a break from Delhi, until Serena decided to renovate it as a luxury homestay.

Luxury, I suppose, means different things to different people, but for me it was in nailing the simple details. Like beautifully crisp linen and fresh towels. Bathrooms that actually make you want to spend time in them. Service that’s intuitive but never intrusive, thanks to Serena’s assiduous training. A steady supply of steaming masala chai, the perfect antidote to the freezing weather. And I haven’t even got to the food yet.

My first morning here, I’m up bright and early, the fatigue of city life having evaporated miraculously into the pure mountain air. I’m famished; another side-effect of this glorious weather. I choose a sunny spot, ring my bell and sit back in anticipation of a homey juice-cornflakes-toast-egg spread, so characteristic of mountain lodges. Instead, a stack of fluffy pancakes accompanied by organic honey and maple syrup, herb-seasoned baked beans, juicy pork sausages, homemade breads and jams and a choice of fresh juices present themselves before me. There was talk of going on a walk through the forest after breakfast but by the time I’m done eating, I can’t move. Besides, winter sunshine is delicious and basking in it is among the best things to do here.

I laze, stirring occasionally to the low din of activity in a far corner, where a new cottage is being erected under Serena’s watchful eye. For the next two days, this is the only sound I’ll hear. The primary lure of this place is undeniably the seclusion and the views: a vista of undulating green hanging in a brilliant blue sky and, in the distance, the glittering snow peaks of the greater Himalayan massif. Entertainment is of your own making: read (or write) a novel, explore the wilds, play board games, chat, sleep.

It’s time to eat again. We follow the sun down a lengthy flight of stone steps to the garden below that sits along the rim of a dappled valley and are joined by Prashant, a gregarious local, who’s bursting with tales of the history and wildlife of Binsar. He’s also a close friend of Ashwani and Serena. The table is inviting with rajma-chawal-bhindi, supplemented by superb Kumaoni vadas and an equally addictive local raita and, as we dig in, we’re fed with stories of a time when leopards would come knocking on the main door of the house. Now, Prashant assures me, they usually stop at the boundary wall.

In the evening, I allow myself to be coaxed by Serena into a short walk down to one of her favourite spots, an expansive meadow marked by a sixteenth-century temple and also pastureland favoured by the neighbouring village cows. Within minutes, there’s a barking deer in sight, then a family of wild boar in our track. “This is the time when leopards set out to hunt,” Prashant informs me. Great! My imagination, heightened by the fading light, begins to run loose as I visualise a hungry feline lurking around every bend. “Darogey toh marogey,” says Prashant matter-of-factly. I break into a half trot till I hit the main road. To the right, misty snow-caps, blushing pink-orange beneath a vibrant sunset, offer a glimpse before vanishing behind a curtain of oak.

Back home, a crackling fire, some wine and a feast of fresh pea soup with garlic bread, roast chicken, baked vegetables, sesame-tossed beans and homemade pizzas awaits, followed by some old-fashioned chocolate cake for dessert. To me, food this excellent in a place this far-flung is perhaps the biggest luxury. Sated, I waddle to bed and collapse into a deep, deep slumber, all thoughts of the leopard buried into oblivion.

Rising at the crack of dawn the next morning isn’t easy, but rise I must as I’ve promised Serena I’ll join her on a longer, apparently prettier, walk through the Binsar forest. I step outside and, in the awakening sun, everything is a gentle gold. We’ve barely headed out of the gate, when we see them — fresh leopard pugmarks, in varying sizes. Filled with nervous excitement, we track them for about a kilometre till they disappear. I’m not sure whether I’m disappointed or relieved.

We’re threading our way to Zero Point, a popular vantage for impressive views of the Himalaya, including the Panchachuli peaks. It’s quiet, very quiet and the crunching of leaves underfoot fills the air. Everywhere I turn, there’s scenery waiting to be photographed: sun-flecked trees, a pair of langurs dangling in mid-air, crests and valleys. In the background, the familiar call of the barking deer. Deeper and deeper into the wilderness we hike, rewarded by fresh sightings of deer and wild boar along the way. Forty minutes later, we’re at Zero Point, in effect a clearing along the mountain edge with a granite machan. We mount it and there it is — a panorama of peaks draped in white. I turn to my photographer colleague, Sanjoy; he looks like he has his money shot. We revive ourselves with more hot cups of tea, cookies and some cheese, before we direct our steps towards home.

I didn’t think that two days would be too little for Binsar. Yet, surprisingly, I’m not ready to leave. Whether I’m prepared to swap the warm shores for the hills is another matter. But I’d swap nerve-wracking Delhi for the easy life here. Any time.

Himalayas

Kumaon

Mary Budden Estate