“Take your shoes off,” my host and guide Eldoz gently suggested as we stepped up to

“This is my favourite place,” Eldoz continued. “Most tourists don’t know about it.” Though he was in charge of showing me around the Woodbriar Bungalows at Meghamalai’s tea estates, there was a childlike, friendly innocence about him. It clearly went beyond being hospitable as part of a job. He really meant it. Within the first few minutes, he had already begun to open up and share his secrets with his quiet and nonintrusive South Indian charm.

Maybe it was the water here. It was certainly doing good things for me so far, slowing me down enough to find endless delight in the fragrance and texture of fresh moss. I felt as if I had always been there, or I had just drifted in with the breeze.

Getting there, though, had involved more than simply transpiring. After two weeks of monsoon tripping through the jungles of Periyar in Kerala, by some situational twists, I had somehow found myself travelling solo to the colonial decadence of a tea estate bungalow, based on the recommendation of a friend who had once participated in a tiger census here.

“It’s a full-on colonial planter’s life out there,” he joked, “complete with a submissive old-worldly attendant who’ll bend over backwards and obey your every command, but it’s got a really odd charm to it.” We had a good laugh then but the ways of the world are funny, and three days later, I found myself seated at a dining table, overeating a sumptuous meal with a personal butler calling me ‘Saar,’ hovering about to serve me constantly, with only my whims on his mind. Inverted bowls were dutifully upturned for my benefit, one by one; dish after dish arrived, gently served, welcoming me on my arrival with more than I could possibly eat — chicken, avial (buttermilk-based vegetable curry), rice, chapatis and vegetables. Then, of course, there was the constant serving of tea.

My original plan in coming this way had been to visit the forests on the Tamil Nadu end of the Periyar Tiger Reserve and meet the rangers there, which I eventually got around to doing after my en route stop at the tea estate bungalow at Meghamalai, the only accommodation around. But like my friend, I too ended up staying at the bungalow longer than I expected, a luxury that is easily accepted after the kind of travel it takes to reach here.

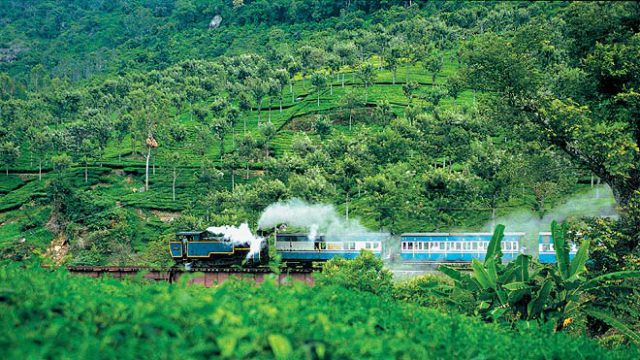

Though Meghamalai borders Periyar’s core forest, the only road route in from the hills on the Kerala side of things was to descend into the plains of Tamil Nadu and then move back uphill into Periyar through the tea estates. The first half of the journey through Tamil Nadu was a mesmerising and colourful riot of urban chaos animated by the glow of dawn, a big contrast from Periyar’s wild tranquility.

The bus rushed through a sequence of busy Tamil towns — an enchanting and fleeting reel of long shadows, beautiful dark Dravidian faces lit with gold and characteristically Tamil colours (bright saris and lungis, vivid billboards with funky fonts, early sippers of chai leaning over the morning papers in front of shuttered shops). A positive energy, overall. At Chinna-manoor town, I had to switch buses and the journey took on yet another dimension.

The first notable interlude was at a tiny roadside temple on the hill slope: the driver and conductor were among the first to get off and pray for luck. What followed explained this well — a gruelling four-hour ride up and through a long and punishing series of craters and whole ponds, swerving through impossible trenches and openings, with the views of the lowlands getting more and more distant.

My hopelessly battered yet totally determined red bus ploughed its way through the clouds and into the mist, rocking and rolling past forests and plantations, tolerating scrapings from dense bushes and pink lantanas, and repeated lashes from tree branches attempting to infiltrate through rattling windows on my long, rough road to a feudal paradise.

Food is the balm for a weary body. Or at least that’s how I rationalised being overfed the second time that day, at dinner. Again, the same routine: inverted containers upturned, curries served slowly and earnestly. Chicken in mint gravy, some chutneys and, as a pleasant surprise, the best dosas ever. Fluffy yet crispy, flavourful but not over-fermented, and served only fresh off the pan, one by one. Moreover, it seemed like I was constantly being served some snack or the other and of course, tea on checked tablecloth. I was in Southie colonial-kitsch heaven.

The temperature dipped suddenly that night, but for the following two days, we had uncharacteristically clear weather for this time of the year, with a charming combination of blue skies and monsoon cloud-fluff. And so it was on our excursion the following morning to Vattapara, an open slope where the tea plantations end and Periyar’s protected forest begins at the Kerala border. Periyar’s elephants, gaurs, deer species and big cats routinely wander through this area, since they are an extension of the same continuous corridor forming Periyar’s core area, known for its rich and well-maintained biodiversity. Nature doesn’t recognise state borders.

Shallow, disconnected streams peppered with islands of fluorescent moss, tiny shrubs, grass and lichens pulsated animatedly with the relentlessness of thousands of cleverly camouflaged adolescent tadpoles (with both tails and legs on). They were rushing downstream in urgent unison, using gravity, endurance, luck and all the survival instincts they could conjure on their journey to adulthood, the only purpose of which was to continue the journey further. It was a manifestation of the raw, abundant energy of life itself, constantly morphing and moving, eternal and far beyond the constraints of mortality.

We made our way through the wet, glossy slope, into a small thicket under a green canopy, where the morning light scratched through translucent treetops, lighting the leaves and creating fascinating spots on the mossy tree trunks. It was enough to just be there in silence and do nothing, detouring occasionally to spy on the private lives of caterpillars and butterflies atop purple flowers waving in the breeze against the mountain backdrop. From the hill opposite ours, a big gaur was checking me out, his black body hidden by the darkness of the jungle behind him, only his huge horns and snout lit by the rising sun.

A late brunch led to more excess. It was looking like a good idea to avoid the inevitably soporific lunch and snack sequences, so I could be alert enough to actually see something outside my bungalow. I visited the Venniar tea factory, a large, automated plant smelling strongly of tea, where Ashir, the friendly factory manager, took me on a step-by-step walkthrough tour of all the processes that lead to my cup of chai. The highlight was a sip-and-spit style tea tasting primer, in which Ashir showed me how to discern the finer nuances of chai flavours, one by one. Basically, you need to sip in small amounts, making suction-like noises, roll the liquid around your tongue, check for aspects such as liquor or ‘furnace burn’ effect, and look really confident as you proclaim your findings. I also learnt that the cool climate and unique high-elevation jungle terroir were among the reasons why the chai grown here had such a superlative flavour, compared to the same tea varieties grown in lower altitudes.

Then we were off to Maharaja Methu, a green and windy viewpoint overlooking the Tamil plains on one side and Periyar’s dam and forests on another. A week previously, when I was sailing past the dam, I first saw Meghamalai, then covered in a shroud of raincloud true to its name, which means ‘cloud-mountain’ in Tamil. I now had a bird’s-eye view of the entire route I had taken to get here on my long journey and this time, it was Periyar that was covered in rain. My understanding of the landscape seemed much more tangible now, as it was with things in general. On my hill were dilapidated remains of an old wall, an old and unrecognisable temple to Lord Murugan, and a much newer idol with a lingam spectacularly perched near the cliff, where locals from the plains come to pray during the Pongal festival. At a police wireless station, a few local lungi-ed boys were hanging out, evidently enthused at the sight of a visitor. “Come, take a picture here… and here…”

In contrast to the freakishly blue skies directly above me, fluffy grey pillars of rain were pouring all over the foggy paddy fields in the Tamil plains, from dense yet luminous rainclouds that were most likely to delight farmers, and they were moving very slowly towards our hill. This place was quite a treat — here before me were the visual and theatrical performances of the ‘marya-megham’ as the monsoon clouds are locally known, with the conveniences of clear weather, all in a single panorama. In addition, karvy flowers, or kurinji poo as they are locally known, were blooming, an event that occurs only once every dozen years or so. I was clearly a lucky sort.

Back to the bungalow, and it was saapadu time once again. An overdose of biryani, plus chicken curry plus Kerala parothas and custard, with a fingerbowl and napkin presented at the end so that I didn’t have to get up and wash my hands in the washbasin nearby. My bedroom, like every other in the bungalow, had a 24-hour ‘butler button’, though it isn’t actually called that. All I needed to do was push it and he would appear.

My guilt was by now beginning to really eat at my otherwise anti-colonial and somewhat Leftist leanings, and climaxed rather comically when once, at around 2am, I hit the butler button by mistake while searching for the light switch in the dark. “Yes, saar?” he appeared instantly like a genie, obviously dragged out of his sleep, looking tortured, but ready to serve, no questions asked. My heart shrank in embarrassment. But yes, he was a really sweet chap. No wonder pioneering Brits braved all the perils of the jungles to set up plantations here. In addition to a paradise of wealth and comforts as incentive, there was also the rare privilege of loyal, dedicated and loving workers, ever-ready to do anything for you.

As I left Meghamalai’s tea estate the following morning, mixed emotionsflooded my mind. Being a nature lover, I could see that these tea estates should be logically included in the reserve forests as a buffer zone, since the animals from the Periyar sanctuary move through these areas and are affected by pesticide use, extension of plantation areas, and the usual consequences of monoculture and man-animal conflicts. There have been long-pending proposals for declaring some of the areas near Periyar’s core zone as a Meghamalai Wildlife Sanctuary to control poaching, create a buffer zone for forest and wildlife conservation, and reduce the use of pesticides and chemical fertilizers. If we don’t protect them now, we will lose the last of our natural wealth for the sake of a few routine business interests.

On the other hand, I had experienced the planter’s way of life, which, like that of a hunter, is controversial but surprisingly far closer to an understanding of nature than that of the urban intellectual, who does all the real damage through his blind economic choices but judges others for their role. After all, we’re the ones who buy the tea, which is why high-altitude forests have to be cleared to produce it. I finally gave up on resolving this cerebrally and decided to live in the moment. And the moment is wonderful, as it always is, when one is aware of nature and not just analysing it.

My thoughts were admittedly situational, since I was about to move to Periyar’s nearby forest station, to meet the hard-working rangers who live without electricity, and brave all sorts of discomforts in the line of duty, quite happily and loving nature. I would learn a lot from them too, but that’s a story for another day. For the moment, I was happy just being where I was, soaking in all the diverse emotions in a hot cup of chai, and enjoying Eldoz’s company.

The information

Getting There

Madurai is the nearest airport (130km). It’s also the nearest railway major station; Dindigul and Kodai Road are other options. A few direct buses (check timings; note that they may vary by up to an hour) ply from Chinnamanoor (43km), the town nearest to Meghamalai, and which is in turn linked with Madurai, Palani, Dindigul, Trichy, Kumily, and Bangalore, Coimbatore and Chennai, with more regular bus services. Access roads up to Meghamalai are hopelessly rough. Don’t attempt them in a delicate vehicle. Only consider bringing an SUV or 4WD.

Where To Stay

The Briar Tea Bungalows(from Rs 5,250; 94422-02001/ 94426- 34125; teabungalows.com) are colonial tea estate bungalows situated in scenic plantations at Valparai, Munnar and Meghamalai. The last is admittedly the hardest to reach but its remoteness makes a visit here even more rewarding. A stay at the Meghamalai tea bungalow is a high-end experience full of old-worldly charm and pampering service. The low-end options in the area are cheaper but far less charming. Try the Panchayat Guest House (04554- 232389/232225), the Forest Bungalow (98421-14647), or the Traveller’s Bungalow (94878- 50508) at Manalar Lake.

What To See & Do

The High Wavys in Tamil Nadu form part of the Varushanad range of hills in the Western Ghats around Madurai, sharing a border with the Periyar Tiger Reserve, known for its wildlife. Meghamalai (at 1,500 metres) was among the last high-elevation areas to be cleared for tea plantation, but it still has some surviving stretches of pristine evergreen forest. Though Meghamalai isn’t on the typical tourist radar, the tea bungalows make for a relaxed getaway, with excellent hospitality and the possibility of wildlife sightings.

Meghamalai

Munnar

Tamil Nadu