By the time the plane emerges from the cloud we’re already low to the choppy grey sea.

Padang, in the middle of the left flank of the Indonesian island of Sumatra, is the capital of the Indonesian province of West Sumatra. Sumatra is almost entirely Muslim, and while Aceh in the northern tip of the island is home to a particularly fundamentalist Islam, which still demands that gamblers be flogged, the rest of the island practises a laid-back mix of Islam and ‘adat’, the old animist and pagan customs of Indonesia. Girls wear painted-on jeans, may or may not cover their hair, and may or may not wear a burqa. People drink. Women like to smoke just as much as the men, even if they tend to do it at home. This is a land full of Chinese, Indian, Bugis and indigenous peoples, and it accommodates everyone.

Driving out of Padang city we head to Bukittinggi, a town nestled in the island’s inland spine of forested mountains. West Sumatra has a look reminiscent of Jurassic Park — lush rainforest, thick buttery sunshine, humidity, epic cloudscapes, decadent flowers hanging heavily off branches. You get the sense that big old things rest and rustle here; apart from the tapirs, rhinos, deer, bears and tigers in these forests, you almost expect brontosauri. This is the unstable land that lies on the Ring of Fire, a land of volcanoes and earthquakes. This was the epicentre of the deadly 2004 earthquake and tsunami. There’s actually an earthquake and tsunami warning on currently, so it’s not a bad idea to be heading for the highlands.

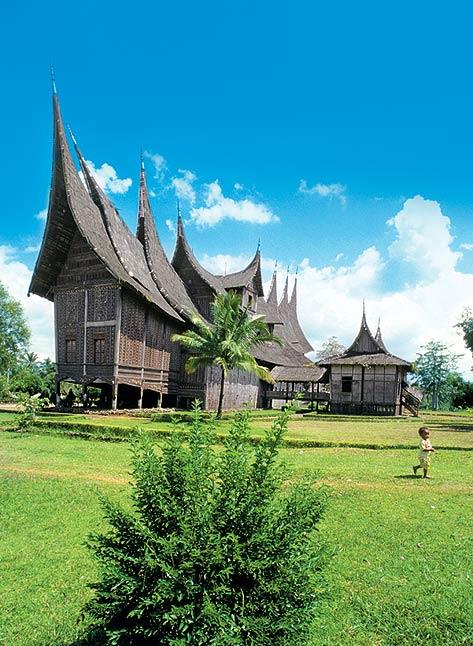

People here are traders, fishermen, farmers and government workers, and things run at a commensurate pace. It’s the home of the Minangkabau people, who have two excellent traits: they’re a matriarchal society in which the women own all the serious economic assets; and they revere their long-horned buffaloes so much that the architecture of their roofs mimics the distinctive peaks of the buffalo’s horns. One of the most impressive expressions of this architecture lies just before Bukittinggi: the Istano Basa Pagaruyung palace. It’s a huge, breathtaking roof with a traditional sago fibre thatch (the newer buildings have zinc roofs that don’t have to be replaced every twenty years), gorgeous painting and supporting poles that lean slightly outward like an endearing squint.

On the two-hour drive to Bukittinggi we stop at wayside shacks to eat passion fruit, fritters and cassava and tapioca crackers. Along the road flutters the occasional West Sumatra flag, whose yellow, red and black colours each signify a different region. We’ve just entered the rice-growing Solok area, where on a tall pedestal in a town plaza soars a sculpture of a five-foot-tall rooster, which turns out to be the town mascot.

Lake Singkarak is a pretty blue smudge at the foot of the Bukit Malalu and Bukit Barisan hills. We stop there to stare at it and nibble on ikan bilis, a fish snack, from the shoreside shacks. You can swim in the lake, but only up to twenty metres from shore on account of it being sacred. Water-sports? Nope. Entertainment? Nope. You just sit, and look, and let yourself relax. I like this. If you’re going to bother to come to a lake, you may as well look at the lake. They do, however, have a Tour de Singkarak cycling event around the lake, which is the second largest in Sumatra.

The road skirts the lake, as does the rail track that ferries a weekly load of coal up the island. Roadside stores sell enormous stuffed toys including Angry Birds. We pass into cinnamon territory, the major crop of the area, and then wide paddy fields and craggy hills. Lunch is at Pondok Flora restaurant, on stilts in a body of water thrashing with well-fed fish.

Ah: food. Padang food is endemic in all of Indonesia because it’s so damn good. It’s shack style, meaty, spicy, made in the morning and served all day, best washed down with Bintang beer or coconut water. Rendang is the famous beef dish, dryish and flavourful. But there’s so much else: chicken, eggs, gado-gado, cabbage and other vegetables, rice and delicious red sambal. If you don’t like your meals tepid then it’s not the thing for you, but I’m not fussy.

After lunch we head to the Harau Valley. Like so many other places in Indonesia, it has a story. They say Harau used to be ocean — the rocks here are different from other Sumatran rock. A Hindu princess who set sail across that ocean promised her fiancé that she would return and marry him, else be turned to rock. Her ship was wrecked in the Harau kingdom during the voyage; rescued by the locals, with no way to return, she and her entourage settled in this new place and she married a local man. One day, her little son’s toys fell into the ocean and she jumped in to save them. Remembering her promise, she prayed to the gods to fulfil her promise, and there she still is, a rock that resembles a woman with long dark hair.

The eleven-kilometre Harau canyon is for walkers, trekkers, rock-climbers and paragliders. It’s a beautiful composition of red, purple, green and ochre rock faces hung with creepers and orchids, lush with cocoa and peanut trees and much else. After a look-see we head off into yet another buttery sunset, though soon a light drizzle turns into a candid downpour, with cars half a wheel deep in water. It’s hard to find beer, much less a cold beer, in small town Sumatra, so we make do with a few warm cans on the bus, and finally arrive at The Hills hotel in Bukittinggi in a cool, velvety darkness hung with stars.

Bukittinggi was the capital of Sumatra for a year in 1948; the first Prime Minister, Bung Hatta, was from here. It’s a small, peaceful town that goes quiet at ten, excepting the odd bar in Chinatown and the neon-lit roadside snack stalls that always seem to have custom. After a traditional Minangkabau dance demonstration — full of sartorial finery and flash, some breathtaking ‘silat’ dancing in which the dance is inspired by animal combat and a really breathtaking dance in which delicate Sumatran women with rose petal feet stamp barefoot on broken crockery — we wander down to one of the open pubs and have ourselves a Bintang or two. Sitting on the breeze-cooled veranda by candlelight (the lights fail at some point), with a beer sweating gently on the table, listening to the kids sing karaoke inside, I conclude that this is all just about perfect.

By daylight, we plunge fifty metres down into the earth to explore the tunnels that were built by the Japanese before they lost WWII. The smell of cool, slightly damp earth and concrete and cloak-and-dagger history puts me in mind of Neal Stephenson’s Cryptonomicon as we wander through 1,400 metres of barracks, dining spaces, jails, ammunition stores and spyholes. It’s a stiff hike back up the 140 stairs; we catch our breath looking out over the beautiful canyon.

Nearby is Fort de Kock, a lookout on the crest of a hill built by the Dutch during the colonial occupation, surrounded by trees and next to the Bukittinggi zoo. It’s a somewhat depressing little zoo; the Sumatran tiger has retired to his tiny concrete cave, the gibbons are swinging morosely from steel bar to steel bar, the orangutans are reaching between the bars for chips and orange juice offered by rule-flouting visitors, and a few pretty birds walk in circles around very small cages.

The Dutch-built clocktower — a squattish, art deco structure — is the major landmark in Bukittinggi. This is where friends and young lovers meet for a smoke or a canoodle, where appointments are honoured and free time is whiled away. Around it sprawls a labyrinthine market filled with batik, fake watches, jewellery, spices and knickknacks of all descriptions.

After another lip-smacking lunch of rendang, deng deng (beef cooked with green chillies), cabbage, chicken and coconut water, we pile into the bus under growling black clouds. On the ride to Lake Maninjau, rain pelts the lush greenery spattered with brilliant bougainvillea. We make a brief stop at the Panorama Sungai Landau spice shop to buy cinnamon and cloves, and to smoke a cigarette in a sit-out overlooking a green valley filled with birdsong and the gentle clack of wooden wind chimes.

Like almost everywhere, Lake Maninjau has a story and, like most, it’s a love story. It’s about a time when Lake Maninjau was an active volcano called Mt Tinjau. In a self-defence competition among villages in the area, a boy named Kukuban fights a boy named Giran. Kukuban’s sister Siti Rasani and Giran fall in love, and when Kukuban unexpectedly loses to Giran, he and his eight brothers decide to teach Giran a lesson by breaking up the romance. They catch the lovers meeting in a hut in the forest; Rasani has lost a lot of blood from leech bites, and her brothers accuse Giran of besmirching her honour. The lovers are blindfolded, paraded in the village and taken to the active crater of Mt Tinjau. They pray to the gods: if they’re guilty, they should die horribly when they jump into the crater. But if not, the mountain should melt into a lake and Rasani’s nine brothers should be turned into fish in that sulphurous lake. As the lovers jump, the mountain explodes and collapses into a caldera, and the brothers meet their finny fate. The villages around Maninjau lake are all named after characters in this legend, and it is said that the fish in the lake are the descendants of the nine brothers.

From the lovely hilltop campus of the Nuansa Maninjau Resort, we drive down the hill to the lake, via Kelok 44, or 44 bends, that were built by Dutch engineers and Sumatran slave labour (there should have been 45 bends, but they forgot one). Snaking through cinnamon and clove trees, and other vehicles negotiating the narrow road coming the other way, it has a gorgeous view of the lake — when it isn’t hidden behind smudgy grey clouds, as it is now; but in the half hour that it takes to reach the shore, sunlight silvers the skin of the water once more. We sit on a wooden veranda at Maransy Beach, sipping coffee and beer, with a breeze playing gently on the surface of the water. Fishermen’s nets lie in ranks by the shore. A fair number of fish float by us belly-up, done in by one of the many tiny underwater eruptions that regularly occur from the active caldera.

We chat, and watch broad pillars of sunlight soaring from the middle of the lake. Life is gooooood.

In the evening there’s a nice little karaoke bar in the hotel, unfortunately for the other hotel guests; after dinner, as a misty drizzle puts everything in soft focus, we belt out a couple of hours’ worth of tuneless songs before hitting the sack.

On the way back to Padang the next day we stop in at Bandai Sikek village, on the slopes of Mount Merapi. It’s a community of weavers and woodcarvers who supply the region with ikat, songkets and beautifully worked doors, lintels and decorative wooden items. It’s also the only Minangkabau village left where these traditional skills are still the mainstay. But there are other villages known for other crafts: Koto Gadang is a village of silversmiths, Sunghi Puar a village of ironsmiths.

Our last stop is at the museum of Minangkabau culture, in a spectacular Minangkabau building. We browse old photographs of old houses and leaders, books and mockups. Even better, we get to dress up in the heavily jewelled silk of Minangkabau wedding finery to have our pictures taken on an elaborate wedding throne — a touristy but irresistible event that makes us feel like a million dollars for five minutes.

Back in Padang, we top off our very rural visit with a short visit to a super-cool nightclub called the Tee Box. Flashing lasers, a mix of pop covers and Indonesian numbers, the vocalists in outfits that put you in mind of Lady Gaga.

As I fall asleep on the last night I think to myself, the times in West Sumatra, they are a-changing, if slowly. This is a place to relish before it turns into a McDestination — a place to treasure for its natural beauty, its anachronistic feel and its unique culture.

The information

Getting there

There are no direct flights to Indonesia from India. A Delhi-Padang return flight (via KL and Jakarta) costs about Rs 63,000.

Visa

Indians are eligible for a 30-day visa-on-arrival ($25).

Currency

The Indonesian rupiah is about Rp 9,455 to the US$, or Rp 166 to the Indian rupee. Don’t get upset if a songket costs Rp 2 million — it takes four months to weave, and works out to roughly Rs 12,000.

Where to stay

In Bukittinggi, The Hills (from Rp 850,000; thehillshotel.com) is a large, comfortable, yet extremely charming 4-star hotel with conference facilities, great food and friendly staff. The Lembah Echo guesthouse (Rp 90,000–450,000 for a room, Rp 90,000–1,400,000 for a cottage; echohomestay.blogspot.com) is a beautifully located collection of 9 cottages on a rise at the mouth of the Harau Canyon. In Maninjau, the Nuansa Maninjau Resort (from Rp 520,000; nuansamaninjau.com) is a lovely hilltop resort with an enormous pool, comfy rooms and tasty meals.

What to see & do

Padang: Padang has a few respectable malls, one of which is cheek by jowl with the spiffy 5-star Best Western Basko Hotel. You can also explore the surfing on Purus or Bangus beaches ($50 for an hour).

Bukittinggi: The price for a guide into the Japanese tunnels is Rp 10,000, but you can bargain if you have a group. Entry to Fort de Koch and the zoo is Rp 5,000. To watch a traditional Minangkabau dance demonstration, check out the Puti Limo Jurai Group every Thursday at 8.30pm (putilimojuraigroup.blogspot.com), a five-minute walk from The Hills. At the museum for Minangkabau culture, you can hire eye-popping traditional wedding costume for Rp 35,000 and have yourself photographed.

Tip

West Sumatra is not a developed tourist destination, though they are on their way. That means that many things are rough around the edges, first among them restrooms. On the many long drives involved in getting from place to place, you are unlikely to find a better loo than the one you’re looking at in horror, so don’t put off until later what you’re loath to do just now.

Harau Valley

Padang

travelling in western Sumatra

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.