The modern metropolis is self-consciously bustling, self-consciously anonymous; its denizens are far

How unexpected, then, that I should find myself at 7am on my second morning in Korea in a dizzying embrace with a K-pop beauty, all crimson lipstick and auburn hair, her breath made sweet and sour by beer and cigarettes. All around us, thousands of strangers were hugging, slapping each other on the back, raising a toast. It was a scene repeating itself across the city. Office towers were empty, shop tills unmanned. I was near Gwanghwamun plaza, watching a huge screen, as traffic slowed while drivers craned their necks to sneak a look. South Korea had scored against Russia in its opening match at the Football World Cup. The Koreans’ goal had injected a tedious game with comedy, the ball from a speculative shot floating through the Russian goalkeeper’s hands like a spectre through a wall.

There were 20,000 Koreans in red shirts in the square, flags painted on their faces, and the girls were wearing devil’s horns on their heads. They had gathered in the square by dawn for the early morning kickoff; when there weren’t rock bands and K-pop dancers, the fans were singing ‘Oh pilseung Korea’, a chant made popular during the 2002 World Cup, which South Korea co-hosted with arch rivals Japan. Over in Gangnam — a ritzy part of town full of skyscrapers, restaurants, clothes shops, and plastic surgeons’ offices — Korean superstar Psy performed ‘Gangnam Style’ as a pre-match treat, for the first time in the eponymous district his ridiculous dance moves had made famous worldwide.

Ordinarily, when Korea’s ‘Red Devils’ (hence the horns so many girls were sporting) play, tens of thousands of fans watch on big screens set up at Seoul Plaza, a patch of green outside City Hall, the new building a glinting glass canopy hovering over the old one, now converted into a library. Reopened in 2004 as a public space, the Seoul Plaza is also the site of public protests. Between December and February, it serves as an open-air ice rink. It is at the heart of Seoul’s public life and as such served as the locus for public grief over the Sewol disaster in April, in which 300 people, mostly schoolchildren, were killed as a ferry from Incheon to the holiday island Jeju capsized.

Korea remains damaged by the deaths, the government nervous about ongoing demands for a parliamentary inquiry and accusations of negligence and cover-ups. Seoul Plaza, festooned in yellow, had become the site of an altar for the dead. In the days leading up to the game, Korean media debated the seemliness of World Cup street parties just two months after Sewol. By kickoff though, Koreans turned out to support their team and, in a difficult national moment, to seek solace in each others’ company. There haven’t been too many difficult moments over the last three decades or so of South Korean history.

Seoul, the ‘Miracle on the Han River’, emerged from the detritus of the Korean War to transform itself into an industrialised hub, an advanced economy controlled by chaebols, essentially family-owned multinational conglomerates, and their government backers and collaborators. The city is a tribute to big business, a dense collection of gleaming high-rises, of bold-face luxury brands. Seoul has thousands of years of history, but it is not a historical city in the way of European cities, where ruins are carefully, pedantically preserved. The vast, famous palaces, destroyed by the imperialist Japanese, are mostly 20th-century reconstructions and there is a theme park quality to them, history as dress-up.

What is real in Seoul, and most palpably influential, is not the Joseon dynasty that ruled the country from the 14th to 19th-century, but capitalism and commercial pop culture. A friend whose father was a visiting professor in Seoul told me her parents were hugely impressed by Seoul’s ‘modernity’. By this, she explained, her parents didn’t only mean the obvious economic development of Seoul into one of the premier global cities, but the cosmopolitan contemporariness of the students, “young, forward-thinking, ambitious people not bogged down by tradition.” There is a smoothness, a slickness about Seoul, about its technology, about the fashionably dressed young men and women on its streets and about Korean fashion and pop culture.

Hallyu, the Korean Wave, is a phenomenon not just in Southeast Asia but also in the west, north Africa and elsewhere. Last year, a K-pop artist sold out venues in Argentina, Brazil, Chile, and Peru; Delhi’s Tibetan colony does a roaring trade in DVDs of Korean drama, while kids from Chennai and Bengaluru leave scores of comments underneath K-pop videos on YouTube. Many young Indians sang Korean songs while participating in a K-Pop Idol–style contest organised last year by the Korean cultural centre in Delhi. It was won by a handsome teenager from Dimapur in Nagaland. Clearly, K-Pop is a popular alternative in the northeast to ubiquitous Bollywood.

It’s easy to mock K-pop as overproduced pabulum — the rigorous, choreographed dance moves and smooth-voiced, smooth-faced, smooth-limbed young men and women who serve as stars. But the popularity of the genre tells us something about the desires and lifestyles we’ve been sold — lifestyles so gently and catchily lampooned in ‘Gangnam Style’. It’s, again as with so much in Seoul, a theme park version of the good life, available for a price at malls everywhere. Unsurprisingly, Seoul is replete with shopping malls, including Asia’s largest underground mall, the COEX, or the Lotte Department Store in Myeong-dong, an area devoted to the acquisition of branded clothing; designer-imprinted bags hanging from wrists like fruit from heavily laden trees.

Fashion in Seoul is extraordinary, not connected to the embrace of any particular lifestyle, with no meaning beyond the clothes themselves. So a punk dressed in vintage Vivienne Westwood bondage isn’t necessarily connecting himself to Johnny Rotten, the Sex Pistols and the music of the period, or the bands’ rudimentary anti-establishment politics, but to a certain look and the look alone. Watching young people in Seoul, in Gangnam, or in hipper Hongdae, can sometimes feel like a trip through the history of British and American pop culture and fashion robbed entirely of context. It’s that theme park thing again. Which is not to say there is no creativity — pastiche in Seoul is a highly developed, sophisticated art. The darker, nastier edge, of course, is the city’s obsession with plastic surgery — the desire for rounder eyes and straighter noses and ‘Western features’ that makes the use of ‘Fair and Lovely’ in India seem like a benign, eccentric fad.

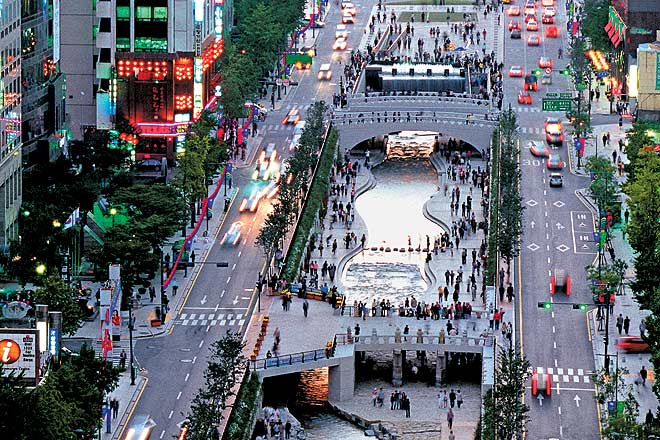

But perhaps this enthusiasm for plastic surgery, for connecting a brighter personal future with reconstruction makes sense in a city that itself is a continuous exercise in reconstruction. The memories of relatively recent poverty, authoritarianism, war and humiliating colonial subjugation are banished beneath the glitter of note-perfect globalised modernity. Perhaps this is mere pop psychology and idle speculation. The fact is Seoul has effected a remarkable transformation, not just a cosmetic one. Now the city is undergoing further change from an ambitious, gritty, industrialised hub into a frequently charming, pleasant, global middle class haven. Typical of the change is the conversion of an ugly flyover, with the kind of traffic snarl Delhi residents will recognise, into an urban park with a resuscitated stream running for miles through its centre and shiny, happy Korean couples and families strolling along the walkways, dipping their toes in the water, eating ice cream on a summer’s day.

On the walls in Cheonggyecheon, you will find photographic reminders of its unprepossessing past — cars pressed bumper to bumper along the tarmac, the fumes, the oil, the baleful frustration — and marvel at the efficiency of urban planning that turns an eyesore into an oasis in a couple of years. And then there is Seoul’s subway system — the most extensive in the world with a parallel, underground city of cafés, shops, markets, restaurants, and free wi-fi. As with so much in Seoul, the subway is a model of efficiency, planning, and technological advancement, a glimpse for the foreign visitor of the future.

Indeed, for the foreign tourist, particularly Indian, the realisation that you’re in a city on a different level of planning and execution is evident when you arrive at the airport in the suburban city of Incheon, an hour or so away from Seoul and part of the wider Capital Area. In September, this city is hosting the Asian Games. Its international airport has been voted the world’s best airport in various polls for nigh on a decade.

Incheon is a microcosm of Seoul — it’s a city with every imaginable upscale urban convenience, chiefly shops and restaurants but also a golf course, free cultural performances, tours for transit passengers of various durations up to about five hours, even a museum. This is the sort of airport in which you might come across lithe, bendy breakdancers spinning on their heads on a Tuesday afternoon, while on Thursday a small crowd of people will have gathered around a startlingly accomplished string quartet playing Ravel.

The airport serves as an introduction to the authorised version of Seoul — sexy but safe, free but within carefully proscribed limits, open and friendly to foreigners but among the most homogenous major cities in the world. Essentially, Seoul is a sanitised vision of seamless prosperity, of free wi-fi, green urban renewal, Zaha Hadid-designed shopping malls and convention centres. It’s intriguing that young people in Seoul appear to view their own history and cultural traditions with the polite bemusement of outsiders, learning to conduct a tea ceremony or sing love-lorn Arirang with wide-eyed enthusiasm but detachment. Their real lives are so unencumbered by the past that among the most popular, if fast diminishing, places to drink in Seoul are the makeshift tents, pojangmacha, constructed with orange tarpaulin and transparent plastic that hark back to rougher economic climes in the 1950s. You know you’re rich when even working-class drinking habits are the subject of theme park nostalgia.

Life in Seoul — fuelled by ambition, industriousness, devotion to partying and reckless credit card debt — is a capitalist dream. Economic progress of an unparallelled speed has made Seoul as complex and interesting a city as any in the world and for the Indian tourist, it is both eye-opening and quite profoundly instructive.

The information

Getting there

Multiple carriers run regular hopping flights from New Delhi and Mumbai to Seoul (round-trip for approximately RS.55,000).

Where to stay

Seoul has many first-rate business hotels. The Shilla (From $300, shilla.net) is an old warhorse, with spectacular swimming pools, spa, and duty-free shopping. Then there are the hip, boutique hotels like the Rakkojae (from KRW 250,000; rkj.co.kr), an elegantly restored traditional hanok (wooden house). To save money, you can hire a bed at a Korean spa for less than $10 in a room full of other bodies made catatonic by the heat of the sauna. Guesthouses can be found in popular tourist areas like Hongdae for less than $50.

Where to eat

Korean food is fantastic, full of spice and flavour, much of it to be found in the several small plates that accompany ever meal. Vegetarians will struggle unless they enjoy tofu; Korean meals revolve around seafood and barbecued beef and pork. North of the Han river, the food is resolutely traditional, all pig’s feet and fried innards. Korean street food is plentiful and widely available.

Galbi is barbecued communal meals, where the meat cooks on your table and everyone shares. Byeokje Galbi is recommended for the carefully selected quality of its meat, its beef from organically fed Korean cows. Then there is Hanjeongsik, a meat or fish preparation that comes with dozens of small plates of savoury pancakes made of fermented octopus and other food that has been grilled, steamed, blanched or served raw. Noryangjin Fisheries Wholesale Market in Dongjak-gu on the river, is a hugely popular tourist attraction where you can buy fresh fish from the vendors and then have it cooked for you.

What to see & do

Sites of historical interest in Seoul include the five Joseon palaces such as Gyeongbokgung or Changdeokgung, and the six remaining gates of the Eight Gates of Seoul, which are built into the fortress wall protecting the Joseon capital. Originally constructed around 1396, the gates, the palaces and much of historical value have been destroyed and what visitors see are perfect reproductions. Bukchon village with its picturesque hanok, is a good example. The neighbourhood also contains bijou galleries, cafes and restaurants. The Blue House, where the Korean head of state lives, is on the site of the royal garden of the Joseon dynasty’s erstwhile palace. Behind the Blue House looms the peak of Bugaksan. There are popular hiking trails up Bugaksan that run alongside the remnants of the old fortress wall.

Seoul has traditional street markets, crowded with cheap goods, as well as exclusive department stores and designer boutiques. Namdaemun, located next to the Great South Gate is the city’s oldest and largest wholesale market. Dongdaemun, designated a special tourism zone, contains both traditional markets and shopping centres. For Korean chic, check out Hongdae and Garosu-gil. Gangnam is best known for its art galleries, design bookshops and hip designer boutiques. You could also check out department stores like Lotte and Shinsegae in downtown Seoul. Yongsan Electronics Market, with its 5,000 shops, is the place to go for bargains on cutting edge technology. Seoul has many museums, including one dedicated to kimchi.

K-pop

Seoul

South Korea

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.