Sitting in the office of a publicity and information officer in Mysore, I was amazed by the

Dasara in Mysore is a heavily policed affair. It has to be, with the kinds of numbers involved, particularly in the grand finale on the 10th day of the celebrations. Lakhs of people assemble to watch the final day’s Vijayadashami procession, also called the Jambu Savari, along its 4.5km route, from the palace to the Banni Mantap grounds. A few thousands manage to get tickets to watch the procession inside the palace gates. The rest gather along the cordoned streets to catch a glimpse as the procession passes by. Many are even less lucky and have to content themselves with watching a live telecast of the procession on a giant LCD screen installed in a large field near the railway station. Having no intention of resigning myself to such compromises, I spent an entire day negotiating red tape until I found myself in the aforementioned lady’s office. “Come back later,” she said ending our discussion, “I’ll see what I can do.”

The Mysore Dasara festivities are spread out through several locations in the city. The palace ground serves as a massive open-air venue with the lit palace providing a stunning backdrop to performances by a string of venerable names from the world of Indian classical arts.

There is a moment worth witnessing every evening, when the sun sets and all 96,200 palace lights come on at once, greeted by a spontaneous gasp of awe from the assembled crowd. Even I was impressed, although I had thought myself immune to such standard-issue tourist postcard images. Less impressive was what followed—a two-hour wait for a bharatanatyam performance to begin, while politicians and bureaucrats took turns making longwinded speeches extolling the virtues of Mysore.

Those less culturally inclined had no reason to complain—just outside the palace an adventure sports company had arranged for bungee jumping. I have never fully appreciated the point of the sport, and so can only guess at how beautiful the illuminated palace must look when you’re upside down and hurtling towards the ground.

Also in the palace grounds was a vintage car display, featuring cars like the 1930 Delage D8 designed by the legendary Italian Guiseppe Figoni before he went into partnership with Ovidio Falaschi, the 1936 Mercedes 170V and the 1939 Ford V8 Van, once an ordinary postal van, now a precious relic. I watched a father posing his toddling son in front of the 1928 Lanchester. “Smile!” said the father. Too young to appreciate the fact that the car he was standing in front of was once owned by Motilal Nehru, the child proffered little more than a grimace before running into his father’s arms, in the process dropping and stepping on a pair of spectacles. The furious father reached over and dealt him a brutal slap across his face. The child stood, understandably stunned for several seconds before bursting into tears. “He just refuses to smile for the camera!” was the father’s weak defence to passersby who admonished him. I walked on, admiring the 1947 MG TC, the 1955 Jaguar XK 140 and several vintage motorbikes, among them the 1956 Triumph T100 and 1942 Norton 500 Military. These were the vehicles that would flag off the Jambu Savari on the final day. As I made my way out, I found the uncompromising father exactly where I had last seen him, in front of the Lanchester, except he was now attempting to graft a smile onto his hapless son’s face by pulling up the corners of the boy’s mouth.

On my first evening in Mysore I went to watch the Yuva Dasara festival being held at the Manasagangotri amphitheatre, featuring several exotic-sounding dances. Expecting something of a cultural show, I was disappointed, to say the least. The one dance I did sit through had four men, one of whom wore a waist-length wig and a white nightgown, and staggered around the stage with his arms outstretched. Another dancer pranced about threateningly with a plastic bag tied over his head, in which two holes had been cut out for his eyes. The remaining dancers flapped their arms and hopped about like epileptic chickens. The piece ended with the lot of them collapsing on stage in a collective death. I did not recognise the music to which this horrifying endeavour was choreographed, but suffice to say it was very eerie. The crowd seemed to differ with me however, greeting the corpses with thunderous appreciation as they took their curtain call.

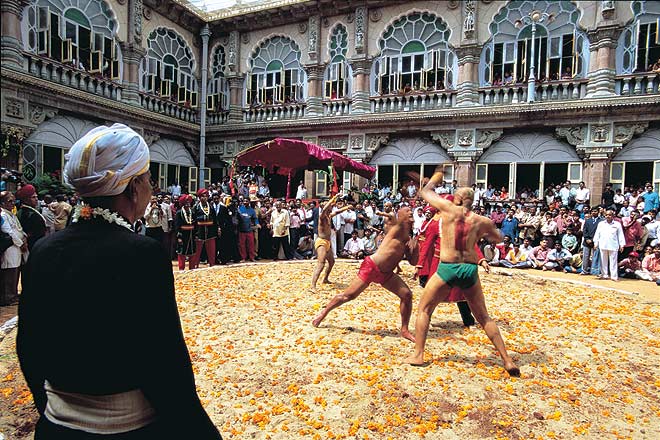

The next morning I wrangled an entry into the palace to watch the maharaja’s ayudha puja on the penultimate day of the festivities, a ceremony that is closed to the public. By the time I argued my way inside the palace gates, the puja was in full swing. The maharaja stood on a dais, decked in flowing mauve robes, with glittering necklaces coiled around his neck and an exquisite turban on his head. A marching band provided romping, if somewhat incongruous, accompaniment to the rites. Camels, caparisoned elephants, palanquins and luxury cars passed before the king; to each he made an offering of flowers before motioning that they be taken away. The band trumpeted on through ‘Serenade in the Night’ and ‘The Cariappa March’, before ending with a rousing rendition of the Mysore anthem.

After the puja I returned to the publicity and information department. To my surprise, the lady officer had my pass for the Jambu Savari waiting for me. Pleased with my success at paper shuffling, I used the rest of the day to explore some of Mysore’s watering holes, visit the theatre repertory Rangayana where a festival of plays was running, and sample some delicious Manipuri food at the food mela being held at the town hall. It was a pleasant, aimless day, and returning to the hotel I reminded myself that the final day was likely to be a little more hectic.

The next morning the streets of Mysore were swarming with people. Inside the palace gates, hordes of policemen had been deployed to make sure everything ran smoothly, even if it meant using physical force against errant members of the audience. One particularly lathi-happy policeman seemed to derive an inordinate amount of pleasure from grabbing and whacking random members of the audience. “It’s good to see a man enjoy his work as much as the police officer,” said a British journalist to me, inexplicably cheerful about the sadistic cop.

Around the palace, the eager crowd climbed up billboards, trees and telephone poles to see what was going on inside. Cannons boomed across the palace grounds, marking the beginning of the festivities. The vintage cars rolled out of the palace gates, greeted by a roaring, adoring public. The rest of the procession followed, the star of which was the elephant Balarama, carrying on its back the idol of the goddess Chamundi.

The range of cultural forms showcased in the procession was staggering—Dollu Kunita, giant Garudi puppets, Shaivite Veeragase dancers, Pata Kunita, Nandi Dwaja…. These were interspersed with tableaus, some celebrating the wonders of Mysore, others freezing moments from the epics, still others celebrating the diversity of religions. My favourite tableau was one warning against the evils of alcohol. A man took a swig of what looked like rum, and pointed menacingly at his wife. She protested feebly. The vehicle moved a few feet forward where the man took another swig of rum, and the woman protested feebly again. I marvelled at the stamina the two actors would need to live in this fleeting theatrical rut for the next three hours, as the glorious Jambu Savari wound its way through the streets of Mysore.

royal festival of Mysore

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.