KoWhen my favourite bookshop in Bangalore shut down, it took with it a chunk of

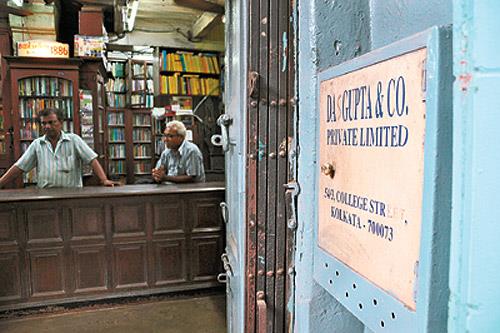

Shacks lined the streets and they looked mundane — the books looked cheap and new — not what I had in mind. As the sun threatened to melt me, I ducked behind them, and lo! There were some old-looking bookstores with high ceiling fans that barely made a dent in the thick humid air. A bored store attendant in one of them waved me away: “Dasgupta’s, oldest.” OK. I walked through the light blue painted wooden doors two stores down, and up to the counter.

Is this the oldest bookstore in Calcutta? “Yes,” beamed an elderly man. “Come, come, and sit down.” A-ha. ‘Booksellers since 1886’ proclaimed an incandescent sign above a bookcase. I spied an ancient iron spiral staircase in one corner and longed to go up and seek the treasures it hid. But for now, I sat down opposite the owner, sixty-year-old Mr. Aurobinda Dasgupta.

In 1886, with just fifty books and in a shop slightly off from where they are currently, Girish Chandra Das Gupta from the prosperous village of Kaliagram (district Jessore, now in Bangladesh) came to Calcutta to doggedly pursue his dream of owning a business here. Those were heady days. Stalwarts like Saratchandra Chattopadhyay, Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar were regular visitors and friends of Girish. “This was the place to be — College Street — this bookshop, and next-door at the India Coffee House. Many revolutionary plots were hatched here, many movements launched.” The family business has seen two world wars, the partition and riots of 1947, and the Naxalbari movement.

I drifted around. This shop, this man, both reminded me of Bangalore’s lost Premier Bookshop and Mr Shanbag. “Do you have this book, sir?” Yes, yes, Shanbag would smile, walk to a label-less pile, rummage and find the book. Hand-write a bill with a small discount. And that was not all. He would remember I’d bought the last time and recommend a book I might like. He was Amazon.com in the flesh!

In Bombay, in the backstreets of Girgaum, you find little hole-in-the-wall shops with such people. Booksellers all their lives, they know their books. First edition of a Premchand? No problem. There’s Strand Bookstore in the Fort area of Bombay, too, another favourite hangout, but not old like Dasgupta’s. Bangalore still has Gangaram’s and Blossom on either side of Church Street, and Select which is off Brigade Road, all places where one can spend hours rummaging and can get good recommendations from the owners. The very old Motilal Banarsidass in Delhi is a bookstore several generations have hung out at, specialising in books on Indology. And speaking of old books, if you are ever in the Mori Gate area of Old Delhi, do find JM Jaina and Sons. The bookstore is not as varied as Dasgupta’sor Strand, it specialises in books on law. But, standing in the same place since 1928, it has a gem few others can boast of: one of the last remaining, original copies of the Constitution of India, calligraphed by Nandalal Bose. Apart from its historical value, it certainly is also a beautiful work of art!

Shaking myself from these meandering thoughts, I asked Dasgupta for old books—handwritten notes, manuscripts from revolutionary days, maybe? He shook his head. In 2004 the whole shop was gutted. “We lost everything, all the books, all the manuscripts.” And they were not insured. Yet, in a few years, Aurobinda Dasgupta rebuilt his great-grandfather’s dream. You can find almost 80,000 books today, sourced carefully and thoughtfully. This moved me immensely, for that kind of dedication is pure devotion.

That old spiral staircase took us up one floor. There were shelves everywhere, lofts with ladders, scattered books, an old typewriter, a small retreat room, a meeting place on the terrace, a stamp stand that probably predates independence and a historic publishing room all came together to make history here. And it had the comfort of an old soul.

We had reached a balcony now, three floors up, and Dasgupta pointed across College Street to an unfinished building. “Book Mall, with many floors of bookshops. It has squeaky-clean floors and air-conditioning. We also have a place there, in addition to this one,” he says.

Then he hastily adds, “But I will still sit here.”

book worms

College Street

Kolkata