I arrived late at night in Tunisia and on the dark deserted roads, buildings stood only as

What I knew about Tunisia before I came, I could fit on the back of a postage stamp: the ancient civilisation of Carthage, the Romans, the Sahara and that Star Wars was filmed there. Oh, and the flights from London were cheap. It was difficult to find local flavour amongst the fresh fruit, cheese, cold meat, croissants, pancakes and cereal at breakfast.

I wondered if Carthage would also be beyond my grasp, willo’- the-wisps of only later Roman ruins, not enough to make the ancient city seem real. Up on Byrsa Hill, I looked out to where Carthage once stood and found little left except a channel from the sea that used to be the military and commercial port. I drove down to it and the small museum with its extraordinary model of the building that once stood there. Hidden in a circular shed were 220 boats, strictly against the treaties with Rome. For a moment I was in Carthage, with its own kind of forbidden weapons of destruction.

Antonine Baths, the best preserved of the Roman sites, was next to the current presidential palace. Armed guards stood in plastic kiosks to scan the ruins for any tourists inadvertently taking photographs of the palace. I thought they made it look like the set of Jesus Christ Superstar and kept expecting hippies to come running out of the ruins singing, ‘who are you, what have you sacrificed?’. This made the children’s sarcophagi lining the paths all the more shocking, sudden reminders of the Roman accusation that Carthaginians sacrificed children.

After the unremarkable modern buildings in Modern Tunis, Sidi Bou Said, a small artist’s colony on the outskirts of Tunis, was bursting with character. Latticed wooden shutters, in every shade of blue, reverberated out from whiter than white walls. Red bougainvillaea-framed doors studded with brass buttons, like join-the-dot pictures of Fatima’s hand. But Sidi Bou Said also had a certain falseness. It was now a catered-for tourist attraction with the main street full of shops selling stuffed camels and leather shoes. The vendors were aggressive, following me up the street brandishing goods.

I love vegetable and produce markets where people are too busy to notice me. In the souks of Tunis, the different trades stuck to areas with street names to match their profession. An old man pushed a wheelbarrow full of fresh mint between the barbers, tailors, perfumeries and jewellers, leaving behind a soft scent as traders bought his wares for their morning tea. Outside the shops, in tiny cages, brightly coloured birds sang of their misery. Inside, small windows in the ceilings of shops let only the occasional shaft of sun into the gloom, so that a spotlight landed on the fez makers brushing red felt with thistles, folding the hat between two boards and adding it to the stack that was their seat.

In the old part of Tunis, the Medina, I was pleased to gain a guide, as the labyrinth of narrow streets was an unforgiving maze to strangers. He wove ahead adeptly, avoiding the many stray cats, to an old house, now a museum. After the plain exteriors, Tunisians traditionally do not display their wealth on the outside, the interior felt like a riot. Yellow and green hand-painted flower tiles encircled the lower half of the sitting room and white intricate stucco rose to the ceiling where crystal chandeliers hung, their light glinting off gold mirrors.

I told my guide I hadn’t found much to see of Carthage. “Ah,” he said, “Carthage and the Romans they are in the Bardo Museum.” There were extraordinary pieces in the galleries, a giant head of Jupiter and his feet from a temple at Dougga. Bronzes from a sunken ship, housed in special glass cases to preserve them as they were found, looking like they were made yesterday. Strange dwarves danced, Eros flew and there was even a bed. A Roman bed. I had never seen Roman furniture before. Still, out of context they felt disjointed and didn’t conjure up the ancient civilisations. The mosaics came the closest with gentle shifts of colour and fine alterations of size; men hunted, fish gleamed, Cyclopes roared and Ulysses struggled against ropes holding him to the mast of his ship so he wouldn’t be tempted to join the harp-strumming sirens with their hidden talons.

For the rest of my trip, I had a driver, Moez, and a four-wheel drive. We headed out into countryside full of fruit trees, young vines, olive groves and barley. In roadside cafés the carcasses of bloodied sheep hung outside. A farmer trotted home on his donkey, his wife and children slowly trailing on foot behind. In fat nests, balanced precariously on top of electric poles, elegant storks with black-tipped wings fed their shrieking young and I started to get a sense of this country’s identity.

The Roman site of Dougga hugged the top of a hill and looked down onto a patchwork plain of wheat and poppies. Wild flowers covering the amphitheatre and temples were coated in white snails. Scraps of mosaic remained on the floors of villas. The ruins came back to life around me in small details. A niche in the lintel of a doorway for a hinge, clay pipes to circulate heat in the walls and a semi-circular conference toilet. In a large empty niche at the temple was where the statue of Jupiter at the Bardo had stood. I wished he were here, here he would command as he was meant to.

Green hills sprinkled with poppies slowly dissipated and were replaced by scrubland stretching into the endless distance. Then even the scrub was gone and it was desert, flat uneventful sand, no dunes, no nothing. Finally a dark green patch of palm trees appeared. We had arrived at the oasis and the town of Tozeur. Outside my hotel were large rocks eroded into strange shapes and dusted pink by the setting sun.

The next morning I attached myself to a group of French tourists and their guide on a route around the Medina. He walked quickly, ignoring several beautiful houses to rush to the house they used to film The English Patient. After a quick explanation he moved on to a door with three knockers, explaining, while continuing to walk, that each made a different sound so the householder knew who was arriving. And on again he scurried and so I let them go. I took a caleche, an impressive name for the sorry horse and cart that bumbled into the heart of the oasis, and was disappointed, as only someone who has seen too many films could be, to find no Omar Sharifs watering their thirsty horses in the shade.

We left in the early morning. Men wheeled portable petrol pumps out onto the pavements and then sat on deckchairs waiting for trade. On and out of the bustle, onto the silence of Chott el Jerid. It was hard to see the solid plain of salt as a lake, until I saw the two channels dug down on either side of the road, an impossible aquamarine, a surreal pink and white.

Beyond Chott el Jerid there was only scrub, until, at Douz, it turned into the fine sand of the Sahara. The afternoon wore on and towns became villages as we wound up arid mountains. Occasionally there were dammed valleys that managed to water a single palm, a fig tree and sometimes a small crop of barley. Higher up the landscape was eroded into desolate crevasses like the surface of the moon.

It was not until I was about to fall into a troglodyte house that I found the deep holes that were homes in the village of Matmata. The central courtyard dug down into the earth with the different rooms, caves of cool, around the edge, safe from the elements and any invaders. As I was beginning to get this new side to Tunisia I wandered into the Hotel Sidi. It still had the props from the bar scene in Star Wars strapped to the dug out walls. Images of just what Matmata had been like before the modern concrete houses, the tourists and the film directors arrived began to blur in my mind.

The next morning was grey and unseen winds slapped and shoved me. A guide led me up crumbling paths to the village of Chenini, which clings in terraces to a mountaintop. I climbed up beyond the cemetery with three stones piled on top of each other for the men, two for the women and one for a child. Past the modern dwellings where most of the villagers now lived, up and up to the old abandoned houses carved into the rock. Berber women, their layers of shawls only held at the shoulder by the brooch their betrothed gave them, scrambled up the slippery path laughing as I crawled upwards hearing the wind scream in my ears. “There are only old men and young boys left here,” my guide said, pointing to a winding path disappearing out to the horizon. “Now that is the way they all go, to the cities, along the old camel trail.”

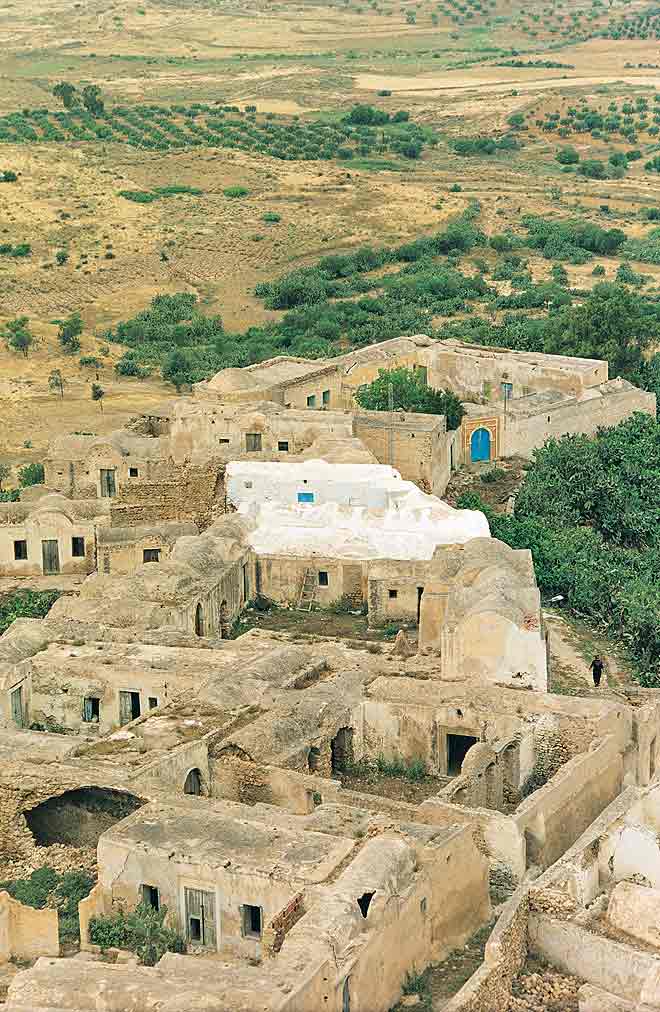

I stayed in Tataouine, a place I had thought only existed in the ‘War of the Stars’ as Moez called Lucas’s film in French. Nearby was a ksour, a fort-like storage house, where the surrounding villages used to store their wealth and supplies. Long barrel rooms with small arched doorways all faced into the centre, one place to defend together when the invaders came. Large earthenware jars sat behind sun-bleached palm doors, as though waiting for owners who had fled. Storm troopers at their door.

I fell asleep on the last ride upcountry to my flight home and when I awoke was surrounded again by miles of olive groves, lemon trees and in the distance the smell and sound of the sea. Moez made me promise to tell my friends, “There is sun, sea, Romans, desert, hidden homes, War of the Stars. Tell them to come to Tunisia, no problem.”

The information

Where to stay: Tunisia receives about five million visitors a year and offers nearly 200,000 beds across 700 hotels. The range, inevitably, is broad. Style-conscious tourists, blessed with deep pockets, usually make a beeline for the Villa Didon in Carthage, 15km north of the capital Tunis. The bright, dazzling white building, revamped by the French architect Philippe Boisselier, is surrounded by ancient ruins, and overlooks the Bay of Tunis. The boutique hotel’s focus on design extends to the Philippe Starck chairs, the low-slung designer sofas in the bar and the red-glass lift (www.villadidon.com). Cheap hotels abound in the capital’s old city area. Try the fancy sounding Grand Hotel de France ([email protected]). All the big chain hotels tend to be clustered in special tourist zones. For a comprehensive list see www.tourismtunisia. com, the official website of the Tunisian National Tourism office.

Where & what to eat: There is, of course, as wide a range of places to eat in Tunisia as there are places to stay. At the Villa Didon, you can eat everything from hamburgers to Italian, Thai and Indian food at Alain Ducasse’s Spoon (Ducasse is the only chef in history to hold six Michelin stars at one time). For an authentic Tunisian meal, try Dar el Jeld in Tunis, arguably the country’s most famous restaurant. Located in a traditional Medina courtyard house, the restaurant has 86 covers and specialities include fish couscous, spinach lamb, olive beef stew and a large variety of pastries (see www.dareljeld.tourism.tn). Tunisian food is famous for its reliance on harissa, a chilli paste used to add zest to stews and sauces mopped up with either the ubiquitous baguette or tabouna, a flat Berber bread. Tunisians also use plenty of olives and tomatoes in their cooking. Seafood is an integral part of most Tunisian meals: Try the rouget, red mullet, either grilled or fried. Couscous is the national dish and Tunisians have hundreds of different ways in which to prepare it. Tunisian snacks include briq, a fried, thin pastry envelope stuffed with egg and other fillings.

What to see: Tunisia has a history of invasions at least as turbulent as our own. It is a country of picturesque ruins. At 164,000 sq km it’s not particularly large, though the landscape ranges from green and hilly in the north to desert in the south, with its famous troglodyte pit homes that served as the set for Star Wars. And there is an enormous amount to see:

— Start in Tunis, where the mazy, atmospheric medina, with its Grand Mosqueé, its souks, arches, coffee shops and Carthaginian columns, is a UNESCO World Heritage site. Tunis also contains the Bardo Museum, a restored 13th-century palace that houses the world’s finest collection of Roman mosaics.

—Close to Tunis, about 15km northeast, is Carthage, site of Punic and Roman ruins, and now, oddly enough, an upscale Tunis suburb.

— Only a little further away is the storybook village of Sidi Bou Said, all cobbled streets and pretty whitewashed buildings.

—In northern Tunisia are the beautifully preserved Roman cities of Dougga and Bulla Regia. There’s also the Jebel Ichkeul National Park, terrific for birding and one of only two UNESCO wetland world heritage sites in the world.

—In central Tunisia, the walled holy city of Kairouan should be on your itinerary, as should the enormous colosseum at Al-Jem, only slightly smaller, though better preserved, than the one in Rome. Sun-worshippers should head straight for the white sand, beach resorts and tennis courts of Hammamet, the Tunisian St Tropez.

—In the south is the palm-fringed vacation island of Djebra and the strangeness of the troglodyte homes in Matmata and the ghorfas of Ksar Ouled Soultane which George Lucas’s film has turned into a tourist locus.

—Make sure to visit a Tunisian hammam, or bath, as well. You can shop for handicrafts, carpets, and objets d’art in any of the dozens of souks you will come across, but if you’re not prepared to browse, scout and negotiate visit the many official, price-controlled Artisanat shops for gifts and keepsakes.

things to see and do in Tunisia

Tunisia

Tunisia tourism

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.