“Brad Pitt. Bill Clinton. And Bob Geldof, but a while

The northern circuit of its historical heritage includes medieval castles, rock-hewn churches, secretive monasteries and a narrative arc that spans the Old Testament traditions of Judaism and Christianity. The fact that all this is subsumed by images of the devastating drought of the 1980s is more a testimonial to the powers of mass media than any real measure of the country. Carry a coat, and prepare to be surprised — Ethiopia is nothing you expect.

Like Lalibela, for instance. The small mountain town lies at an elevation of 2,500m. One reason why we are standing under a tree, gasping for breath after a brisk walk up a steep slope. Lalibela is famed for its spectacular churches carved out of rock. Predictably, for a place of such surreal beauty, its origin lies in a dream. According to legend, King Lalibela, the twelfth-century ruler of the region, was directed in a vision to create the churches as a replica of Jerusalem. The result is a collection of eleven churches in two main clusters, said to represent the earthly and heavenly Jerusalem mentioned in the Bible. To protect them from damage, Unesco has erected giant white umbrellas over some, not quite spoiling the view but certainly making photography a challenge. Despite this, the churches are as epic a spectacle as intended.

Camouflaged from the outside world, the churches are easy to miss. To see them, you have to descend into the mountain. Walking down, the first, overwhelming impression is of bold harmony. Pillars carved out of the red rock stand framed against an azure sky. In the ancient verandas and leaning against the gnarled texture of the walls, monks sit flicking through books a few hundred years old, wearing white robes and wrapped in deep blue shawls. The perfect coordination and the fastidious detailing of beauty makes the whole thing seem like an elaborately choreographed set; the unreal location for a big budget period film. The fact that the monks are at ease with gawking tourists, and that the elaborately dressed priests happily pose for hundreds of cameras every day, adds to the feeling. But despite the touristiness, it is impossible to mistake the churches for anything other than what they are — places of living, enduring spiritual practice and tradition. Each time we enter a church, Taye kisses the pillars and bows his head before the priest. Services see priests beating drums and dancing rhythmically, we are told, while rows of worshippers stand and chant in unison in the ancient hollows of the mountains. Some of the services go on for hours, and Taye shows us the wooden crutches supplicants and priests use to stay upright. This is Christianity as it was practised centuries ago, stripped down to its ancient, pulsing heart.

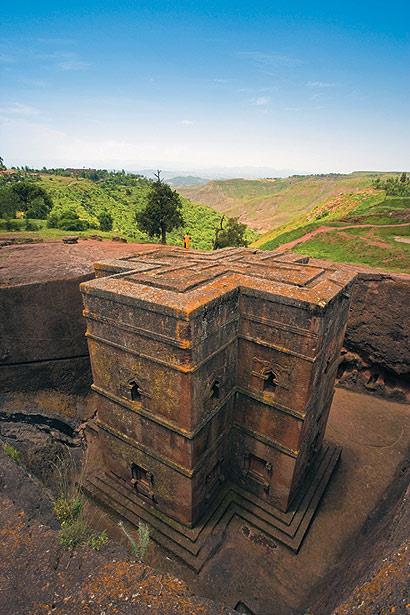

Narrow passages and sloping tunnels cut through the rock connect the churches. As we negotiate our way around, a blind priest comes through a narrow ellipse in the stone. He doesn’t miss a beat on the uneven floor, but counts off his rosary as he walks, following a map only he can see. We work our way through the two main clusters, but pretty soon one rock-hewn church begins to look much like the other. As a closing treat, Taye takes us to the church of St George, a monolith carved in splendid isolation in the shape of a deep, definite cross.

Having exhausted the churches and ourselves, we head back to our hotel through the streets of the town, which are redolent with earthier pleasures. The smell of brewing liquor fills the air and, in front of a house with blue window frames, a small hand written sign says ‘Hisss’. It turns out to be the local video parlour, screening the Mallika Sherawat thriller. Later in the evening, we pass the owners, two young boys. “How was the movie?” we ask, and they give eloquent shudders of enjoyment. “She was very scary,” they report. If Ms Sherawat were ever to visit Lalibela, they wouldn’t just wave and walk past.

Our next stop is Bahar Dar, a charming little town with attractive waterfront vistas on the edge of Lake Tana, a vast sea-like expanse of water from where the Blue Nile begins its journey through Egypt. But like most tourists, we are not here for the city, but for the island monasteries on the lake. To get to the ferry station, we hop into an Indian-style autorickshaw, simply called a ‘Bajaj’ here. Our driver turns out to be a government servant moonlighting on the weekend, who spends the short drive describing a recent training programme he took at Coimbatore. Like most Ethiopians, he recalls being taught in school by Indian teachers. “I send my kids to Indian [administered] school,” he says with obvious pride. “In Ethiopia, if the school is Indian, it means it is good.”

Perhaps as payback, he helps us negotiate with the ferry owner, a reckless looking lad with a mop of windswept hair. Most tourists prefer to spend at least half a day island-hopping, but we are mainly interested in Ura Kidane Mihret, one of the more accessible monasteries on the Zege peninsula. The deal turns out to be less than a bargain, as we find ourselves pitching in a very choppy lake, in a boat with shattered windows and a leaky floor. As we slowly roll towards a perpetually distant peninsula on a very lonely lake, I notice water lapping at my feet. An hour later, we dock at Zege, our boat looking even shabbier next to the sleek tourist launches. Our tension dissolves in the calm of the island, however, where a rock-cut path leads to the monastery. The road is lined with small shops, selling cotton scarves, small replicas of the papyrus tankwa boats that have sailed these waters for centuries and wooden boxes with painted Ethiopian cherubs.

The church of Ura Kidane Mihret is a smallish, circular structure, with shallow steps leading into the dimly lit chamber. Stepping inside is like experiencing a visual electric shock — each inch of the wall is lit up with luminous frescoes, bright and brazen in their imagery. We spend a happy hour looking at bloody decapitations, graphic images of torture and gleeful demons chasing saintly figures who look pretty fed-up. It’s evening but the attendants wait courteously till we’ve gazed our fill. As they lock up, the ticket seller, a Mithun fan, treats us to his favourite moves from Disco Dancer. On the ride back, we pass small islands, and I can just see the spires of their isolated monasteries peeking out from behind dark green groves.

Our final stop in north Ethiopia is Gonder, Africa’s Camelot, three hours from Bahar Dar on a good road, and easily reached by shared minibuses that leave from the bus station. Or so we were told. After an hour of sharking passengers away from other buses, and being abandoned in turn, our driver is finally coaxed into leaving. On the road, he screeches to a halt for prospective passengers. At a large intersection he waits patiently while a passenger haggles over a chicken, which is finally trussed up and thrust into the back with us. We limp into Gonder by evening, exhausted and smelling of poultry, yet strangely elated at having ‘experienced’ Ethiopia.

Gonder is a popular base for hikers heading into the dramatic Simien mountains, though a good road has made day excursions possible. The city itself is worth a trip, too. Its main attraction is the Royal Enclosure, a cluster of castles built by the seventeenth-century ruler King Fasilidas. The beautifully wooded grounds are dotted with structures added by subsequent rulers. Fasilidas’s Palace, the oldest castle in the compound, is also the tallest. They say that on a clear day you can see Lake Tana from its watchtower. We wander around the complex, climbing stairs that end in gaping space, photograph the purple flowers scattered over the ruins and try to understand the complex mechanisms of the royal sauna (without success).

There are other sights, including Fasilidas’s bathing pool outside town and the church of Debre Berhan Selassie, with its 104 Ethiopian cherubs adorning the ceiling. But being fickle tourists, we opt to spend the day exploring the winding lanes of the Piazza instead. Falling in the shadow of the Royal Enclosure, this part of town was shaped by the brief Fascist invasion of 1936, and the mix of medieval African castles and Italian art deco gives it a quirky charm. It is also abundantly supplied with coffee bars, where espresso machines as old as Mussolini hiss out potent macchiato shots. Another relic of the Italian invasion is the easy availability of pasta, which makes a nice change from the Ethiopian staple of injera — a flat, gray bread eaten heaped with little mounds of vegetables, stews and meat. In the evening, we sit in an outdoor café overlooking the town’s busiest square and watch dusk fall over the city. The voice of Aster Aweke (‘Ethiopia’s Aretha Franklin’) on the radio soon mingles with the strains of traditional music and singing floating in from a club down the road.

North Africa’s historical circuit continues further to Axum, its spiritual heart and the resting place (according to Ethiopians) of the Ark of the Covenant. But we turn back, retracing our steps towards Addis. The cool climate and green vistas of its rolling streets, framed by the surrounding Entoto Hills, belie its scale, with a population of around four million, and growing. For visitors, it is a friendly, easy place to explore, on foot if you can take the sudden steep climbs it thrusts upon you. Bole Road is the most ‘buzzy’ part of Addis, with its trendy restaurants, coffee shops, well-stocked bookstores and shopping malls. But the faded colours and graceful façades of Italian-influenced architecture lining the Piazza make it the more picturesque neighbourhood.

I am keen to see Lucy, once the oldest known hominid skeleton, a replica of whose 3.5 million-year-old skull is on display at the National Museum. She got her name from the Beatles song that was playing when she was discovered, but her Ethiopian name is far more apt — Dinquinesh, meaning ‘thou art wonderful’. Sadly, the museum is closed for an international conference, and we can’t get in. Instead, we head for the very grand Holy Trinity Cathedral, where the emperor Haile Selassie was reburied with his wife in 2000, twenty-five years after his death. Outside the church, school girls in blue uniforms kneel on the flagstones, lips moving in fervent prayer.

After a sun-kissed lunch in the graceful Taitu Hotel, the oldest hostelry in Addis, we visit Mercato, the fabled hub of Ethiopian commerce and the largest open-air market in the country. The claim that you can find anything you need (or don’t) here is no idle boast — there are entire areas given over to electronics, handicrafts, spices, coffee and Ethiopia’s favourite legal narcotic: chat leaves. Despite its ‘watch your back’ reputation in the guidebooks, Mercato turns out to be fairly tame for people with experience of chaotic Indian bazaars. We enjoy the narrow gullies and colourful banter of the shopkeepers, at least until they promptly abandon us on sighting Caucasian customers. On our way back, we stock up on powdered coffee at Tomoca’s, and sip their macchiatos, brewed in their gleaming machines and served hot in tiny cups lined up on the ’50s-style counters.

That evening, our taxi driver-cum-guide takes us for dinner to the Dashen Restaurant near the Sheraton hotel. The small stone bungalow is charming, the food is excellent and there is live music. A gorgeous girl in a white dress shimmies to Amharic pop, followed by a young man in a leather jacket who mouths mournful love songs. Finally, a short, stout singer takes the floor and starts belting out a ‘twist’. Within seconds, the two middle-aged couples on the next table abandon their dinner and join him, as does the group of twenty-somethings lingering over their drinks. Soon the entire room is on its feet, snapping their fingers and boogying with their shoulders. As the beat fills the small room, they beckon us to join the fun, and we do, dancing with the rest of them, ‘twisting’ like you can only in Ethiopia.

The information

Getting there

Ethiopian Airlines (ethiopianairlines.com) flies daily from Mumbai (for Rs 32,000 return) and five times a week from Delhi (Rs 34,000) to Addis Ababa. Emirates (emirates.com) also provides connections via Dubai.

Getting around

The best way to get around north Ethiopia, especially if you’re short on time, is by air. Ethiopian Airlines flies daily between Addis Ababa and Lalibela (from $370 return), Bahar Dar ($304) and Gonder ($336). Tip: if you hold Ethiopian Airlines tickets for the international sector, you can get a nearly 50 per cent discount on domestic flight.

Taxis ply in Addis and can be hired for the day (90-120 birr per hour; 1 birr=Rs2.6). A cheaper option are the shared minibuses that run on major routes. In the north, most hotels provide transfers from the airport (around 50 birr), sometimes included in the tariff. In Gonder and Bahar Dar, auto-rickshaws ply for a modest price (10-40 birr), lower if you share. Hotels and guides also help with booking cars for day trips and tours (from $100 per day).

Where to stay

ADDIS ABABA We stayed at the Addis Regency Hotel (from $65, addisregencyhotel.com), which has a pleasant location, excellent staff and good food. There are upmarket options like the Sheraton (from $570; sheratonaddis.com) and Hilton (from $290; hilton.com). The oldest hotel in town, the Itegue Taitu Hotel (from $25, taituhotel.com) has a timber-flanked façade, cool whitewashed walls and friendly service.

LALIBELA The building boom has increased the quality and quantity of hotels in Lalibela. We stayed at the Seven Olives Hotel (from $30; www.sevenoliveshotels.com), one of the older hotels in town, located a two minute walk from the churches. The rooms are basic, but lie in pleasant, wooded grounds. Among the newly constructed hotels, the Mountain View Hotel (from $45, mountainsviewhotel.com) is located on a dramatic cliff edge, and has the best views in town.

BAHAR DAR We stayed at the Hotel Papyrus (from $30, papyrushotel.net.et), a little away from the lakeside views, but with a nicer ambience and a pool. Among the newbies, Summerland Hotel (from $35; enjoybahardar.com) enjoys the best reputation, while the Tana Hotel (from $65; www.ghionhotel.com.et), a government run property has the pick of the lakeside locations. For a more budget option on the lakeside views, head to Ghion Hotel, a government property now gone private, where cottages on the lakeside go for $15-20 a night.

GONDER We stayed at the Hotel Atse Bekaffa (from $25), which has a prime location and great service, but has seen better days. Just down the road, the Quara Hotel has clean rooms though in a noisier location for a slightly higher price ($35-40; www.quarahotelgonder.com). The government-run Goha Hotel (from $60, ghionhotel.com.et) on the hilltop has a spectacular view of town.

What to see & do

In each of the cities, a good way to kill a few hours is a traditional coffee ceremony. Most restaurants, hotels and even the airports provide the elaborate service, with women in traditional clothes brewing the coffee from beans which they roast as you watch.

ADDIS ABABA Visit the National Museum to see the replica of Lucy, our oldest known ancestor, followed by a trip to the Holy Trinity Cathedral, where Haile Selassie was reburied with his wife. There is also the modern but scenic church of Kidus Istafanos, near Meskel Square, which throngs with worshippers on Sundays. The Imperial Palace looks imposing, but resist the temptation to take out your camera; photography is strictly forbidden. For shopping, head to Mercato, the country’s large maze like market, or Shiromeda for traditional costumes. Explore the cafes and juice bars of the Piazza, at charming corner shops like La Parisienne, or sip lattes with trendy young things at Bole Road at Kaldi’s. For coffee powder, try Tomoca’s on Wavel Road near the Piazza .

Habesha Restaurant on Bole Road has excellent local food, in a pleasant outdoor area. There is music and traditional dances in the evening. Sangham Restaurant also on Bole Road is a favourite for Indian food. Itegue Taitu Hotel in the Piazza has friendly staff and a varied menu. The charming Daschen Restaurant near Sheraton Hotel has good food in a not too noisy musical ambience.

LALIBELA Spend the day at the rock-hewn churches (350 birr admission, valid for three days) followed by shopping in town for handicrafts and wooden replicas of the Lalibela cross. If the eleven churches in Lalibela are not enough for you, drive out to the surrounding countryside for more as a day trip. Or just sit at the pleasant restaurant in Seven Olives and enjoy the view.

For lunch, we tried the simple but attractive Blue Nile restaurant for some good local food. The Seven Olives Hotel has the best location as well as a varied menu for dinner, which you can eat sitting outdoors on stone tables, lit by twinkling lamps. Reservations required.

BAHAR DAR Spend the day monastery hopping on Lake Tana’s islands, or just take a cruise on the romantic source of the Blue Nile. Boat hire for half a day is around 600-800 birr, all prices are negotiable. At Uda Kirane Medret, (and most other monasteries) the tickets cost 50 birr each, and give admission to the museum as well.

For the more adventurous, an expedition to the Blue Nile Falls is in order. Minivans and local buses run from the bus station, and take between 30 minutes to an hour on a very dusty road. But be prepared to be underwhelmed — the falls have been sadly shrunk by a hydro electric project that diverts most of the water.

Bahar Dar is dotted with small, cosy cafés, where you can enjoy fresh pastries and fruit juice. Walk down the main street along the waterfront, browsing the second hand bookstalls on the pavement, or get your shoes shampooed by the roadside like the locals do. The Central Café opposite Papyrus Hotel gave a great breakfast, while the fried fish at Ghion Hotel comes battered with breadcrumbs. Tana Hotel has a multi-cuisine option restaurant, but most people will do a basic pasta with tomato sauce just fine.

GONDER Start with the Royal Enclosure (100 birr admission), exploring the ruins of Africa’s medieval castles. The ticket to the Royal Enclosure also gives entry to Fasilidas’s bath, a short drive outside town, and is only valid for the day, so plan your time around this fact. The Church of Debre Berhan Selassie is a fifteen-minute walk from the Royal Enclosure, and is famous for its 104 smiling cherubs decorating the ceiling.

Walk around the Piazza, soaking in the Italian atmosphere and drinking macchiato in art-deco cafés with which Gonder is abundantly supplied. The Quara restaurant has options between Ethiopian food and pasta.

Africa

Bahar Dar

Ethiopia