Every time I walk along the Chowringhee, northward from Park Street, past the metro, the air begins

The Indian Museum, Kolkata, is one of the earliest museums in the world. It owes its origin to the Asiatic Society of Bengal, where the collections first began to be acquired in 1814. Nathaniel Wallich, a Danish botanist, is credited with being the founder-curator of the museum. The museum was completed and opened for public display in 1875. Covering a frontage of 312 feet, it was designed by W. L. Granville, who also planned the GPO and the High Court in Calcutta. Its establishment is closely linked to the upsurge of early modernist movements like the Brahmo Samaj and the setting up of pioneering educational centres.

Spread along three floors, the museum houses the Archaeological, Art, Anthropological, Geological, Industrial and Zoological sections. Entering it from the main gate, and having deposited my bag outside, I am greeted by the half-giant figures of yakshas, placed like dwarpaals (doorkeepers). Any visitor will casually meander among these and more figures only to reach a map of the ground floor. A large quadrangle surrounding an open turfed space is placed centrally, around which are arranged the various sections on three floors. All along the outer colonnade skirting the quadrangle are sculptures, lintels and intricate pilasters. It often happens that, as the afternoon light merges into dusk, these figures change moods. You might have looked at a lion-faced gargoyle many times before, but only at that precise moment of fading winter light, you discover a jarring new perspective.

Walking along the second floor, in the east verandah, hallucinating thus in conversation with the sculptured ghosts of the Sunga dynasty (2nd century BC), the Buddhas, and the protean avatars of Vishnu, I was first startled and then comforted by a familiar face. You will find here, inset in the wall, the portrait bust of John Anderson, the first superintendent of the museum (1865-86), peeping out at you, in black stone.

A walk through the Archaeological Section of the Medieval Age, on the ground floor, leaves me with strange archetypal memories of an artist’s fantasies. Arranged in 20 bays are sculptures of different Indian schools, from the beginning of the Christian era to AD 1200, and some from Java and Cambodia. Keeping in mind the Buddhas in various postures along the outer colonnade, the headless Buddha from the Vengi School, in this section, reminds me of a Roman toga—the slim, transparent outline of his attire merging with the stone austerity of his figure.

As I enter the Egyptian Gallery on the second floor, a guide triumphantly announces to his customers, the centrally placed mummy, 4,000 years old encumbered in a glass case in a death aroma of camphor and other chemicals to aid its own preservation. Yet, what leaves me hung over, after a stroll through the Meteorites, Rocks and Maps section on the ground floor, is a casket filtering through cobwebs, made in Kaimur sandstone. This section also displays the Charnockite series of rocks, which were first recognised and described in India, named after Job Charnock, whose tomb at St John’s Church is made of the eponymous stone.

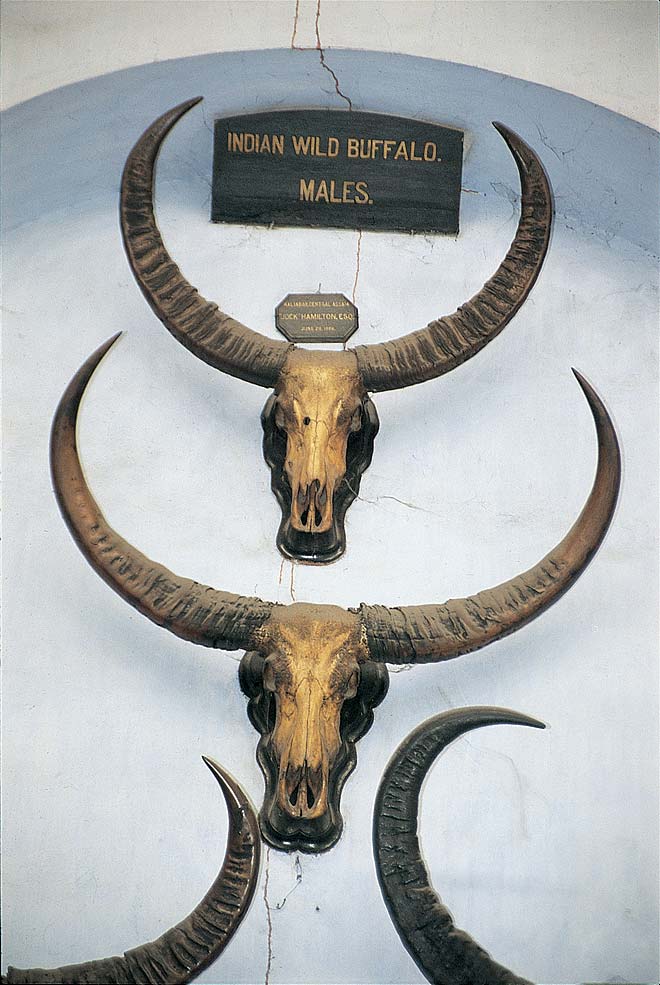

Entering the Zoological gallery, despite the dioramas displaying various species of animals and birds, and the overhung skeleton of a whale, I am mystified by the gaze of the heads of ibex, wild goat, oryx, gazelles and spotted deer, their horns steering into the ceiling space, their skulls disfigured by time.

The Indian Museum has been a centre for cultural dissemination. In 1978, it began mass education programmes with school and college students, organising memorial lectures and short courses in museology. If the muse of history haunts you, you may end up visiting the museum again. As I leave the museum, the evening light cuts the heads of the hawkers selling clothes, coins and trinkets. Just a gate, and you are back into the stream of the present.

places to visit in Kolkata

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.