In the still cold air of the snow-filled couloir, there came an utterly hair-raising musical sound—encompassing the

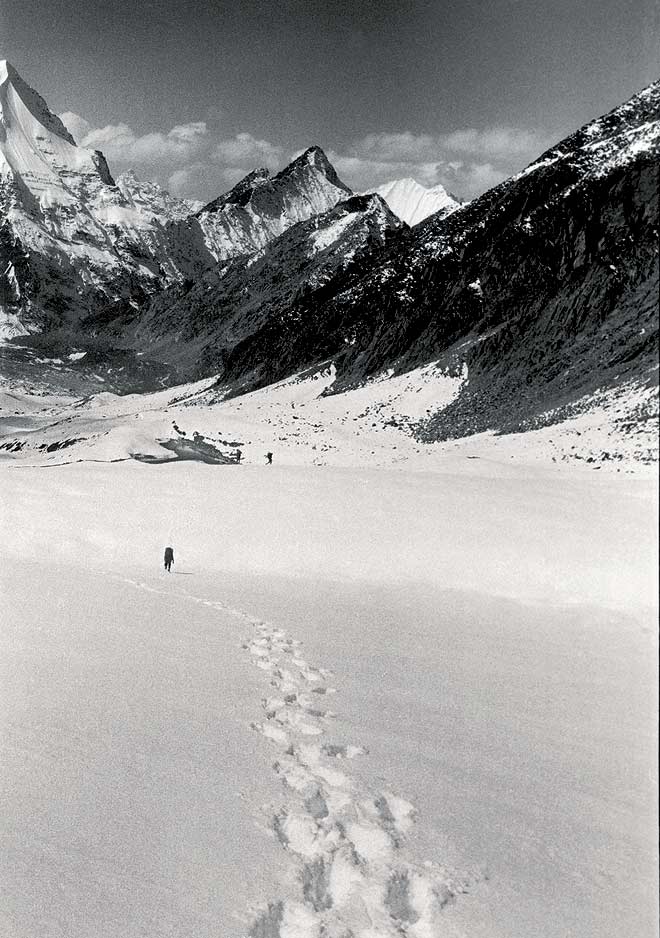

“Pick up your rucksacks and let’s go. Let’s cross this section as fast as possible,” said Alam, accomplished mountain guide and skier who was accompanying Arun, my climbing partner, and me on a climb of Hanuman Tibba. We followed him quickly with Bhagat, the HAP (high altitude porter), bringing up the rear. A massive avalanche had tumbled down the couloir perhaps a couple of days before our arrival and the knee-deep, soft snow made trudging up with heavy rucksacks difficult.

“Helmets should be worn when crossing the couloir. But none of the expedition reports that I glanced at said so,” I muttered, to no one in particular. To make the painful progress up the couloir bearable, I tried to divert my thoughts from the effort of placing each foot ahead of the other on an incline that grew steeper—to about 50 degrees—as we moved up. I recalled the help we had received from one of my climbing friends and mentors, Dorjee Lhatoo, who had been part of an expedition that had made the first winter ascent of Hanuman Tibba many years earlier. I shuddered at the thought of climbing it in winter.

It was also pleasant to think of how the expedition had come about. At 19,450 ft, Hanuman Tibba was none too challenging but I had decided it would do for a preparatory climb before an expedition to Kamet (25,447 ft) that I was launching later in the season. Besides, Hanuman Tibba (the last peak in the Dauladhar range as it joins the Pir Panjal range) soars above the popular “trekking peaks” (technically unchallenging peaks) that pepper the Pir Panjal rather strikingly above Manali and, eyeing it during an ascent of Shitidhar (17,252 ft) the previous year, I had promised myself I would return soon to attempt it.

Well, I was here now and so thirsty that I tore off my goggles and the scarf I had pinned from ear to ear to protect my lower face from sunburn. A row of six-inch icicles hung from an ice formation before me. “When icicles hang by the col…,” I thought, delighted to paraphrase Shakespeare, and bent underneath to lick the melting ice. As the icy drops went down my throat, Alam’s voice carried down, “Stupid girl, you’ll get a sore throat.”

In the late afternoon, as we neared the site of Camp I, the weather changed dramatically. In a few minutes, the heat and glare of sunshine reflecting off snow was replaced by a chill as clouds and swirling mists took over. Camp I was on a rocky platform to the left of the couloir just below its top. After adding a windproof jacket to ward off a chill as the sweat evaporated, we set about levelling the rocks and erecting tents. Then we melted snow and brewed tea. Meanwhile, the guide and porter ferried some food and gear to Tentu La (15,500 ft), the col (pass) at the couloir’s top, burying the stuff in the snow and weighting it down with rocks. Then, cradling mugs of tea and soup in our cold hands, we spent as much of the evening outside tents as possible, acclimatising to the low oxygen levels. At this height dusk took longer to arrive and we could look back down the couloir and the valley and retrace our route.

We had set off four days earlier from our picturesque transit camp amid firs, deodars and pines at Solang Nullah, about 18 km above Manali. It is possible to stay in a hotel in Solang but we chose to camp. Here, on day one of the expedition, our provisions, tents, ropes and other gear had been loaded on mules. It was the end of May and the trek to the night halt at Dhundi (about 9,000 ft) had been hot. The 9-km walk had taken us across Phindri Nullah bridge and on to the Dhundi meadow from where we caught our first glimpse of Hanuman Tibba. The next day’s trek took us 6 km uphill to a large cave at Bakar Thach (10,800 ft). En route we crossed the Beas river via a massive snow bridge. To the left lay the rocky Seven Sisters massif and from the cave we enjoyed a magnificent view of one of the peaks—the 15,000-ft Priyadarshini, named after Indira Gandhi who had climbed it while on a visit with her father in 1958.

Day three had seen us establishing base camp in the Beas Kund area (the source of the Beas) on a grassy field beside a stream, laying out our stock of fresh vegetables in the sun to get rid of decay-inducing moisture. We were now at 11,500 ft and kept ingesting water, tea and soup through the day to help our bodies make more blood to acclimatise to the lower oxygen content of the air. The next day, we had our last meal of eggs (painstakingly transported by hand from Solang to base camp by Bhagat) before setting off to tackle Tentu La.

The wind at Camp I died down after nightfall and we slept well. We had been joined on the rocky ledge by a couple of Germans and their guide, Tika Ram. The Germans’ arrival was fortuitous, as the next morning proved. We wound up Camp I and climbed to the col only to find our cache of food had been broken into and some biscuits, noodles and chocolates were missing. Alam, cursing to high heaven, said he had spied pugmarks in the snow. “The blasted thief is a cunning snow leopard,” he said. More likely a famished fox, I thought. Once the dump was uncovered, choughs (yellow-beaked mountain crows) must have flocked to share in the booty. The Germans’ food helped tide over the situation—especially as bad weather struck the very next day, hindering progress by a day.

From the col to the site of Camp II was an easy and breathtakingly beautiful walk passing dimpled snow dunes bordering a snowfield as smooth as cream. Above the glacier, the south face of Hanuman Tibba soared into a deep blue sky. The camp was beside a greenish-blue mountain lake and we no longer had to melt snow for water. However, the next day, these vistas were swallowed up in a whiteout. Clouds, mist and a drizzle of snowflakes kept us confined to our tents except when we visited one another with cups of instant chicken soup which seemed more delicious than ever.

To our relief, the morning dawned clear and sunny. Quickly, we ate, packed and set off for Camp III. The route traversed more of the gigantic glacier before swinging left to the base of Hanuman Tibba. This was our summit camp at 16,800 ft and, once the tents were erected and the inevitable soup was on its way, I walked to a slope above my tent and looked up at the peak. Suddenly, I had a good feeling.

It was clear, cold and crusty as we left camp at 2.30am on June 2. Hundreds of pinpoints of light shimmered in the inky blackness overhead. The snow crunched underfoot. The wind was light and the air crisp. We’d downed tea and instant noodles before leaving and there were glucose biscuits, chocolates, juice, dry fruit and a coconut for puja on the summit in the three light backpacks between us.

We crossed the snowfield between the camp and the base of Hanuman Tibba’s southeast ridge, then sat down to wait for daybreak. The rest of the route was along the ridge right up to the summit and involved both snow and ice climbing. As it grew light, we set off again and Alam and Tika Ram shared the task of breaking trail—paving the way for the party by plunging through the soft upper layer of snow. I led for a while and set a pace that left the Germans exclaiming that they were not habituated to Himalayan climbing. At the foot of the summit slope, the gradient sharpened to a little over 45 degrees and we donned crampons and roped up. The sun was blazing by now and the trail became slightly slushy as we tramped along in one another’s footsteps.

And then, just past 9am, we were on the summit—a hump marked by a small rocky patch. Above it, a bank of wind-deposited snow sheared up into the sky. All around, the striated snow-cones of the Pir Panjal and Dauladhar mountains dropped away. We shook hands and posed grandly for photographs, holding up the Indian flag tied to an ice axe. After the puja, as everyone chomped on coconut and raisins, I chose a small flake of dark grey stone to carry back as my souvenir from the summit of Hanuman Tibba.

Dhauladhar range

Hanuman Tibba

Manali