The security guards look perplexed and doubtful. They aren’t accustomed to having camera-toting visitors in hats and

The walk befittingly begins at the disused lighthouse, the oldest structure in the complex, a fluted Doric column built in 1838. An elegantly soaring sentinel in stone, originally lit with oil and wick, it encases a spiral staircase (which can’t be seen) and stands on a laterite foundation that marks the mean sea level. It’s 135ft tall, but was eventually abandoned because, well, it wasn’t tall enough. We looked up on what was a terribly hot day, but tall trees loomed everywhere, and leaves rustled in the uplifting sea breeze as we strolled by to the majestic main building.

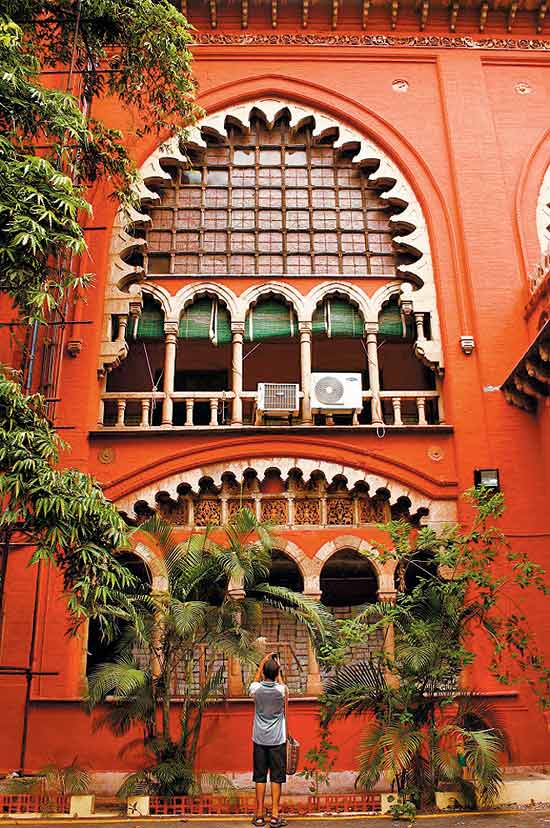

The next two hours spilled over with charming vignettes: the eccentric yet secular amalgam of Moorish, Islamic, Hindu and European styles that come together in the stunning façade; the ‘passive solar’ construction which cools the main complex naturally and gives it depth with the play of light and shade; how Namperumal Chetty was the contractor of choice for many of the city’s colonial landmarks; the High Court’s ceremonial traditions that were meant to awe and subdue witnesses; furniture with jaali work that’s also seen at the Humayun’s Tomb; the trapdoor that brought prisoners up for sentencing; the non-standardised interiors of the courts, some shorn of embellishment, others ornate (nobody knows why); the library and museum (the latter is open to the public on all working days); statues and paintings with epic stories behind them; honourable judges, fearless barristers, progressive thinkers, and cases that set radical precedents. Fali Nariman once described this as the finest court in India, and I would like to think he wasn’t referring to the frescoes and lintels alone. Oh, my racing pen just couldn’t keep up with all of it.

Senior advocate M.L. Rajah and architect Tara Murali, who led the walk by turns, contributed immensely to its value. Their combined understanding of their subject came from two different perspectives – Murali’s eye for visual detail and deeply felt concern for the threats faced by the city’s heritage architecture, and Rajah’s thoughtful erudition and fascinating stories on legal luminaries who strode like colossi down these corridors. Together, they brought the stately edifice to poignant, witty and inspiring life.

The Madras High Court Heritage Walk is co-organised by the Madras High Court Heritage Committee and Intach’s Chennai chapter on the second Sunday of every month; there is no charge; +91-9841013617

heritage walk

Madras

Madras High Court

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.