Sioux obstinately climbed the wrong way, a tough, stubborn mustang that didn’t deign to notice my frantic

Our Native American guide Gabriel rode on ahead with Gael, my friend with whom I set out on this road trip through Arizona. So far, Gabriel has been taciturn. He’s bundled in a heavy blue jacket, a white hoody and a hat covering all but his eyes. His red riding pants are muddy and evidently well used. This ride into Chelly is a two-day excursion organised by the Totsonii Ranch. Back there, Shorty, the ranch hand, had asked gruffly: “Are you good riders?” Gael and I mumbled something about how long it had been since we’d both ridden. I had a vague memory of being around ten years old, sitting on a horse led by some ghorawallah in a park in Bombay. Then, ten years later, I’d ridden a mule once. That was the extent of my experience. But Gael and I had been assured that eight-year-olds could ride independently on this overnight excursion, so we figured we’d probably swing it.

Now, with Sioux huffing her way back up the trail, snorting when I pulled at her bit, I was no longer sure. Eventually I yelled for help. “Hey! She’s not listening to me!” Gabriel galloped up and thwacked Sioux with his little branch; right away, she responded, turning back down to the canyon.

Canyon de Chelly is a smaller and less well-known cousin to the nearby Grand Canyon and Monument Valley, and this relative anonymity made it even more exciting for me. Its history is fascinating, from being the home of the ancient, missing Anasazi (meaning ‘ancient enemy’ in the Navajo tongue) to having witnessed the attempted genocide of the Navajos by the US government in the nineteenth century. The canyon is completely within tribal lands, the Navajo Nation.

We reached Totsonii Ranch an early November morning. It seemed empty, nearly abandoned, the only signs of life a few horses inside a stockade. Then a short man in filthy jeans and matted, dreadlocked hair and beard appeared. We tried to talk to him but it seemed hard — I wasn’t sure when he had last spoken. Later we discovered that Shorty, as he was called, was fifty-something, a Vietnam vet from New Hampshire. Gabriel had found him under a bridge in Chinle, shivering. His sister had tried to put him in an institution or home of sorts, and so he had left, hitchhiking all the way across the country. “Me and Shorty, we get along,” Gabriel said, simply.

We walk our horses on a dry creek bed, moving at a gentle pace on the canyon floor, three men on three horses surrounded by high red sandstone walls, and green, orange and yellow trees. Nothing moves except the wind, rustling dry leaves, swaying branches. Cotton-wood trees are bursting golden, their leaves a burning yellow, so intense it feels unreal. We ride. Suddenly, a herd of horses, in gleaming brown and black coats, breaks out from a copse of trees and gallops ahead of us. “Whose horses are they?” I turn to ask Gabriel. “No one’s,” he says. “They’re wild.”

We go left past a soaring canyon wall and a tall pinnacle of rock appears, a finger of orange sandstone pointing to the sky, in the middle of a junction of canyons in the valley floor. The tower is Spider Rock, home of the Spider Woman, the creator of all things, who taught the Navajo how to weave — clothes, blankets, their turquoise and feather spider-web dreamcatchers and life itself. It’s also the star of the iconic scene in the 1969 western Mackenna’s Gold — its lengthening shadow pointed the way to the legendary canyon of gold.

It’s late autumn, nearly winter, and very, very cold. We stop for lunch and light a bonfire. Just walking around, looking for dry brushwood, feels good. My legs feel a bit bent by now. Soon, I could walk with a cowboy swagger, I think and smile. We make quick sandwiches of jerky, bread, mustard and lettuce. The cold is intense and the low autumn sun is sharp, bringing everything into relief. Gabriel points to a formation in the sandstone, an arch of rock. “Window Rock,” he says. Indeed, the arch reveals a window of blue sky in the rock.

We ride another two hours, or maybe three. The sun reaches the canyon floor for only a few hours in the day. Finally, we reach a field surrounded by a fence.

As soon as we take the saddles off the horses, they run off to the dry field and turn somersaults in the dust, scratching their backs. The three of us sit around the roaring fire, which is disproportionately big, high enough to be seen from miles away. It’s to frighten away the coyotes, the cougars and the skin-walkers, the Navajo shapeshifters, humans who take animal form.

Cedric, or CD, has driven down on a dirt track coming up on the dry wash on the opposite side of the canyon. He’s a young, jovial Navajo, a relative of the ranch owner. I can never be sure when he’s serious, because he says something with a straight face and, a second later, cracks up, his wide round face suffused with giggles. He’s made Navajo tacos. “Navaa-ho ta-coss!” exclaims Gabriel, grinning and chuckling for the first time all day.

Cedric’s been cooking inside the hut. He’s made Navajo frybread (similar to Indian puris), which we pile high with beans, raw onions and lettuce and salsa. Alcohol’s forbidden on the reservation, so we wash it all down with cans of Pepsi, sitting on logs next to the fire.

Gabriel chews his words like a piece of tobacco. “When Kit Carson, when he came around here, he rounded up everybody and sent them south. Sent them on the long march, everybody; 730 miles, you know? Seven hundred and thirty miles, he made them walk. So many died. He just left them on the side.”

Gabriel spoke about it as if it were something that had happened just a few years ago. But the Long Walk of the Navajo actually took place in 1864. In the chaos of the American Civil War, the Navajo rose up against the white man. Brutal violence was committed by both sides. Then Colonel Kit Carson of the US Army forced the Navajo out of their traditional homelands to an internment camp some 500km to the south. Many died during the eighteen-day forced march. Cedric adds, “You can hear their ghosts. In the Canyon del Muerto. They say you can hear voices; they’re searching for their families.”

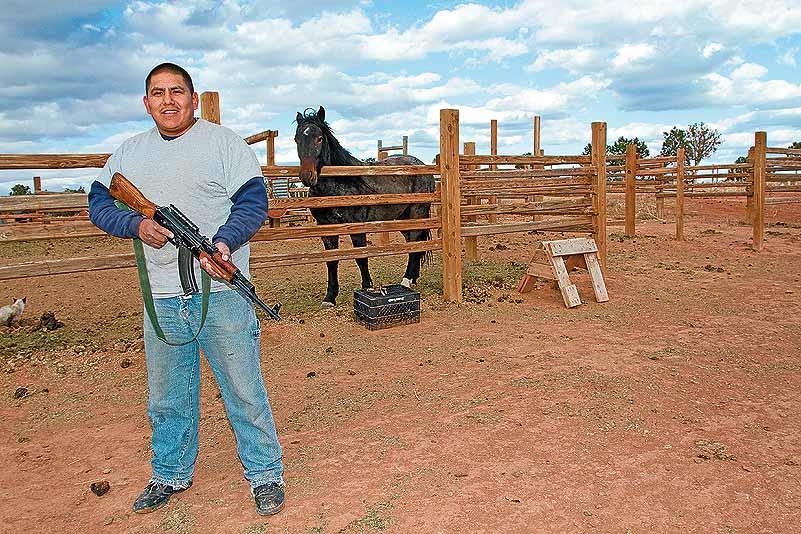

CD’s also well armed. When he realises Gael and I are into guns, he shows us what he’s packing — a civilian AK-47 (legally required to be single-shot and not fully auto) and a 9mm pistol. Why are you packing so much heat, we ask. “For the skinny-walkers,” he says, smiling. Again, I can’t be sure if he’s serious, but I smile back. Gael, a rational Frenchman, presses: What? What’s that? Cedric seems to get a little more serious. He first tries to navigate away from the subject. Then he tells us a story.

“We were night riding back from where you entered the canyon. There was a moon. Suddenly there was a coyote in front and the dog, he decided to chase the coyote. And right there, running out in front of us, the coyote split into two. The two coyotes then split into many more and they began to surround us on all sides. I started firing my AK at them. The dog, he got scared and came right next to us.

“After the sun set, everything turned pitch-dark. We see millions of stars above and, outside the fire, a blackness. We know that we are miles away from civilisation, from the world of men, from help, from computers and cellphones that don’t work here. Here, shapeshifters and ghosts could well be real. We are in ancient lands, we are in old America, of shamans and spirits, before the White Man came.

“And then we rode on, trying to reach here as fast as we could. The coyotes stayed just outside, never getting hit, never howling, nothing; they just disappeared.”

Skin-walkers, as CD explains, are men who take animal form. They use a coyote, wolf or bear skin. Then, through witchcraft, they can become the animal. They walk at night, or run incredible distances. Both Gabriel and CD tell us of various encounters they’ve had. That night, Gabriel has another. At around three in the morning, I hear something moving outside the tent. I hear him get up and walk around, making a lot of noise. I hear him put more wood in the fire, stamp his feet, shuffle around. In the morning, he tells us he had heard something heavy, breathing hard, moving impatiently, staying just outside the firelight.

We ride again the next day. On the canyon walls, we see ruins, tucked into niches high up. Toeholds have been cut into the near-vertical soft rock. Nearly a thousand years ago, the Anasazi farmed on the canyon floor and built their homes up in the rock, and painted signs there too. Then they ‘disappeared’, or so the legend goes. And the Navajo came.

I had joked earlier with Gabriel about how we were both Indians, just from different places. So he asks me, without a trace of malice or irony, “Do you speak your tribe language?”

The information

Getting there

Canyon de Chelly — one of USA’s designated National Monuments — is situated entirely within the Navajo Nation, a semi-autonomous Native American territory, in Arizona. The best way to access the canyon is through the airports in Phoenix and Tucson in Arizona. Both have international airports serviced by major carriers, including Continental, American Airlines, Air India and British Airways (from Rs 56,000 for a round-trip economy class ticket ex Delhi or Mumbai).

It’s best to hire a car from your hotel to the canyon. From Phoenix, it’s a five-hour drive and from Tucson, a six-and-a-half-hour drive. Your hotel could also arrange the tour with an authorised Navajo guide to show you around the canyon.

Getting around

Hotels in either city may provide free shuttle services to and from the airport. Cabs are also easily available. Note that a gratuity (ranging from 10 to 20 per cent) is widely expected in taxis, at restaurants and bars. But the best way to get around is usually hiring a car for your entire stay. Check car rental companies Enterprise (enterprise.com) or Hertz (hertz.com), both located within the airport. Public transport in the US is usable only inside some major cities.

Where to stay

The Thunderbird Lodge (from $75; tbirdlodge.com), on the canyon’s periphery, is closest. It is actually a drive-in motel, with clean, neat rooms and a cafeteria serving local cuisine. The property was built on the original nineteenth-century trading lodge of the area; a bit of history the nearby chain hotels can’t claim.

The View Hotel (from $220; monumentvalleyview.com) is the only hotel within the Monument Valley national park; owned and run by Navajos. Plan early, as the hotel can be booked out months in advance. Each room has a jaw-dropping view of the Mittens, the fantastic sandstone towers in the valley.

The White Stallion Ranch (from $180, including meals and activities; wsranch.com) is a horse-riding resort experience that feels like the other end of the scale from the Totsonii Ranch that we visited. This is a real dude ranch, with fantastic barbecues, large bungalows and nearly individualised rides through the Saguaro desert.

What to see & do

Canyon De Chelly: Our ride into the canyon was organised with Totsonii Ranch, which is the best known of the several in the area. Tariff: day trip to the canyon from $60 per person plus $60 for the guide; totsoniiranch.com.

Monument Valley: The much-filmed and photographed mesas and buttes here are part of the Colorado Plateau. It is close to the Navajo Nation reservation. Entry: $5 per person, additional $10 per person if you want to camp there.

Montezuma’s Castle: The best-preserved ruin in the National Monument is the so-called Montezuma’s Castle, a multi-storey housing complex built into a cliff wall by the Sinagua Indians around 700 AD. Entry: $5, no charge for children under 16.

Saguaro National Park: This park on the edge of the modern city of Tucson takes its name from the Giant Saguaro cacti and houses several rare trees and plants. Entry: $10 for privately owned vehicles, $5 for people on foot or bikes.

Resources

The National Park Centre’s website (nps.gov) is a useful resource for information on the Canyon de Chelly and other parks. Call the Visitor Centre (+1-928-6745507) in Chinle for further details.

Canyon de Chelly trail

cowboys

Mackennaâ??s Gold