It has almost become a game by now: How long in a new place before I hear

And then, as the gaze trips over an emptied lot holding the remains of a magnificently domestic ambition, I begin to see the light. The Vohrawad is coming down, bit by bit. People have been leaving for years. And the houses left behind have been coming down close on their heels. The street wall they once formed together as a sun-shield now has many holes through which the sun reaches down to the street. As the warmth of community life developing on shaded otlas and streets ebbs, the sun begins to scorch the emptier streets a bit more every summer.

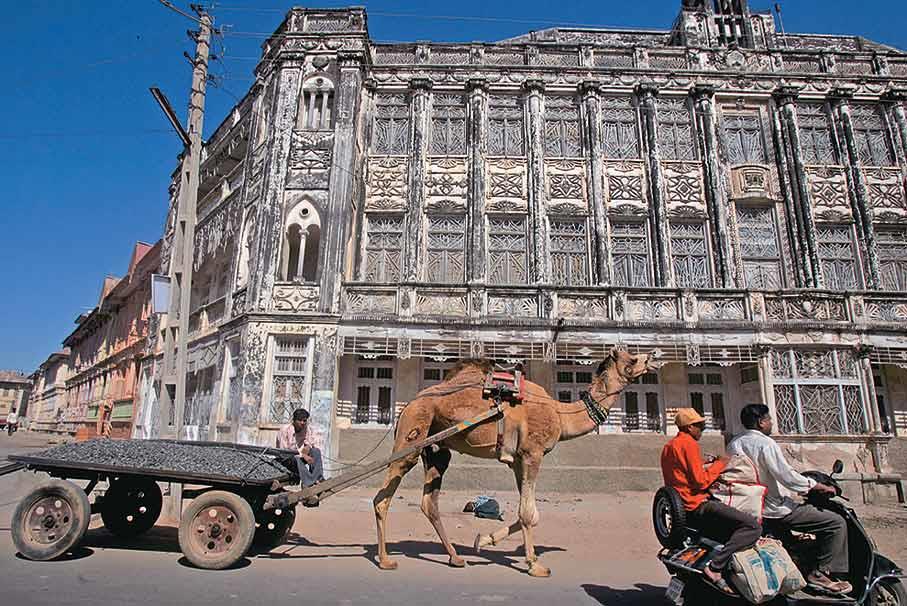

You can put both down to trading success, the petit-bourgeois magnificence of the Vohrawads of Kapadvanj and Sidhpur, as well as their ongoing and literal dilapidation in slow motion. The Bohras here are an old Shia Muslim trading community, with a distinctive social, economic and cultural history. They have spread across the state and the country over the centuries, in response to trading opportunities and, occasionally, threats of persecution.

These Vohrawads, like their older relation the pols of Gujarat, are modern-but-traditional gated enclaves organised around a main street which branches off into narrower side streets that either terminate in cul-de-sacs or, occasionally, loop back to rejoin at some other place. Houses share common walls, have a narrow street-side but are easily four times as deep going in. The compact footprint — necessary for security, quick pedestrian access, and insulation from the extremes of hot and cold weather — is compensated by piling up more than one storey above the ground floor. A very small ‘grilled’ shaft of open air, called the chowk, runs up through the central room of all the floors bringing in a controlled amount of sun (and when the gods so decree, rain), and provides visual connection across the different levels. Decorative wooden extensions of the upper storeys often project out from the building line, in the older vohrawads particularly, and together with similar projections on the other side of the street, help keep the sun out from the street floor. Even by day, then, the street is a cool, shaded space. No wonder the otlas, or extensions of the high plinths, are carefully designed to be lounging spaces, particularly once the sun weakens. All this is, of course, much like in any other old settlement in the hot and dry landscapes of the country. What makes the Vohrawads of Kapadvanj and Sidhpur special is the peculiar combination they reveal of an intimate formality, and exquisite craftsmanship in wood enlivened further by the subtle and uplifting play with colour. Fundamentally, however, the language of the Vohrawads is memorable for a different reason: it is an architectural patois of sorts, assimilating the sentiments, the values and the turns of phrase of different traditions to a language that has the strength we often (mistakenly) associate only with ‘purer’ traditions.

Relatively speaking, Kapadvanj is home to the minor tradition of Vohrawad building. Sidhpur is where the greater architectural drama is. But on the day I visit, it is Kapadvanj that is livelier. Maybe because it is a Sunday, and there are more kids around, some playing cricket outside the mosque near the gate. Or just that it is a smaller, more intimate neighbourhood, where even one or two people in the street bring it alive. There are two Vohrawads at Kapadvanj, actually, close to the main market area and entered through an arched twin-gate leading to the Nani (or smaller) Vohrawad on the left and the Moti (bigger) Vohrawad on the right. In the triangular space between them is the main mosque of the neighbourhood. But during my wandering it starts becoming clear very early on that it is not the delicately imperious clock-tower of the mosque that I have travelled more than a thousand kilometres to gawk at. Nor is it the intricacy of the wooden carving, the grace of decorative plaster, or the subtle polychrome of the façades all around me. It is all that, of course, but none of those things for their own sake.

How do I say this? It sometimes appears as if the pious term, ‘composite culture’, does not actually mean anything concrete to anyone any more. As a corrective, then, Sidhpur and Kapadvanj offer a quick glimpse into the odds-defying elegance, the liveliness, the poignancy (or precariousness), and the sheer fractiousness of composite culture. Just before I left Ahmedabad, a fellow architect had joked about Sidhpur, by way of priming me for a delicious surprise, saying ‘ekdum Haussmann’. I was mystified by the admittedly loose reference to the (in)famous Baron Haussmann — the man who cut grand geometric swathes through dense residential quarters of 19th-century Paris to fashion the urban image we have of it today: a military march of perfectly aligned building blocks, their scale, height and decorative styles closely synchronised but allowing for decorous variation. What could the grand iniquities of long-ago Paris have to do with a provincial town of 50,000 in a northern corner of Gujarat?

I got my answer as we drove through the town asking around for (what some texts called) the Bohrawad. It turned out that there was more than one, to begin with. The chaiwalla’s 13-year-old boy also brought my bookish terminology into alignment with ground reality with an exasperation obviously reserved for the slow-witted: “Aur suno, Bohrawad nahi, Vohrawad bolo”. And then, as we headed deeper into town towards the river (and hence deeper into history since Sidhpur was founded upon the banks of the Saraswati that is largely dry today), we passed quickly by a sudden bit of European townscape — a short military march of perfectly aligned building blocks, their scale, height and decorative styles closely synchronised but with the hint of polite variation revealed even in a quick glimpse. It was gone before I could stop the car to confirm that this was what had caused my friend to remember Haussmann. When we finally shed our wheels at Hassanpura, near the river, we had travelled back to the 13th century when the oldest Vohrawad in Sidhpur is supposed to have been founded. Next door, the legendary ruins of the Rudramahalya complex built in the 11th century by Siddhraj Jaisinh, the Solanki ruler, lay under the purely talismanic protection of an ASI notice.

Over the rest of the day I would wander through three different Vohrawads. Each was different. Hassanpura’s two main streets lurched ahead with the usual axial uncertainties of older settlements. The houses were much more modest with occasional flashes of ornamental brilliance cheering up the general spirit of neglect. By contrast, the one in Harariya, a gated community built further away from the river in the late 19th century, had straight streets, almost equal house-widths, and looked much better finished and maintained. In both, there were the ubiquitous rubble heaps that spoke of the vulnerability of this architecture to the occasional torrential cloudburst, and to the resulting rot that absentee owners usually did nothing about. But in both, older women spontaneously invited us in to show off the intricate carving of the woodwork and furniture. Perhaps there was something about both neighbourhoods that let these women feel secure enough to invite strangers whose cameras were their only visible bonafides. No such luck turned up at the last Vohrawad we wandered through at Najampura, an eerily empty array of streets connecting two busy market roads near the clocktower, and notably without the urban closure of gates. Najampura’s very European architectural decorum seemed to reflect its very approach to sociability. An occasional (and faint) smile, no conversation (except with a poor relative and caretaker living in the basement of a locked house), and no question of any invitation to enter. And yet, I kept walking up and down the street baffled and fascinated by these domestic monuments that modified a basically Hindu house-plan to cater to a Bohra lifestyle, and fused both to a colonial façade of European inspiration (that reflected the international exposure of the trading community as well as its close trade relations with the British). The composite whole — neither this nor that, but something else completely — successfully transformed the very ideas and images it had borrowed. European classicism, for one, has never looked so convincingly Gujarati. At a time when we pride ourselves too quickly on the ability to toggle identities and change selves on the run, here was some perspective: a fairly traditional minority community could borrow blithely from the competing traditions of its neighbours and rulers, to fashion a durable cultural identity for itself almost a hundred years ago. That this should now cause wonder, says a lot about the way we have come to be today.

The information

Getting there: Sidhpur is on the Ahmedabad-Delhi highway and train line. Kapadvanj makes do with a narrow gauge connection. But both places are well connected to Ahmedabad (which is also the nearest airport) by private and state transport buses (Kapadvanj is 70km east of Ahmedabad and Sidhpur approximately 130km north).

Where to stay: Both Sidhpur and Kapadvanj are easy day trips from Ahmedabad. But if you want to stay close to Sidhpur you could try Hotel Siddharth on the highway. This is a low-end hotel run by a staff from South Kanara. The food is competent and the tea was a relief. There aren’t too many other accommodation options so ensure that you don’t get a highway-side room here or the roar of the trucks won’t let you sleep. For food in both towns, there are thalis available, but do try the delicious range of chana dal savouries (served with a special sweet-sour sauce), like gota and fafda (widely available in street-side eateries).

What to see: Kapadvanj and Sidhpur are small towns in Gujarat with long histories connected to Rajput, Sultanate, Mughal and Maratha rule. The Dawoodi Bohra houses and Vohrawads these two towns are known for were mainly built over the last 150 years, except for the oldest Sidhpur Vohrawad (near the river in the Hassanpura locality) which apparently dates from the 13th century. Both were substantially developed in the 11th century by the Solanki king Siddharaj Jaisinh, who also lent his name to Sidhpur. Both also have impressive monuments largely built during his rule. Kapadvanj has the Battris kothri-ni-vav, a stepwell of significant size now turned into an unapproachable dump yard. There is also an equally old and graceful tank of the same inspiration as that at Modhera (which along with Patan is not too far away) with exquisitely crafted stone pavilions and a lonely, towering torana. Sidhpur also has the Bindu Sarovar, apparently the only place in the country where a Hindu matru-shraddha can be performed. The visitor may also be struck by the ease with which aesthetic values and strategies run across the noticeably distinct Bohra and Hindu architecture. For instance, at Sidhpur, the colour strategies used in the Bohra façades are very similar to those used in the Bawaji nu Math (an ashram on the other side of the Saraswati) and both also show a strong colonial influence.

The built heritage of these towns is disappearing fast in the face of governmental and community apathy. Till only a couple of decades ago, apparently, the tank at Kapadvanj was a favoured leisure spot (a cool hangout by the water in summer, literally) for all communities. Its exquisite peripheral stone structures have all disappeared into the ever-hungry maw of the international market for antiques that operates through Jodhpur and Jaipur. This same market encourages owners of dilapidated or difficult-to-maintain houses of the Vohrawads to dismantle them and sell valuable decorative components.

Literature: Sidhpur’s Vohrawads are the subject of two studies by architects: Madhavi Desai’s Traditional Architecture: House Form of Bohras in Gujarat (Galgotia, 2002) and Zoyab A. Kadi’s Sidhpur and its Dawoodi Bohra Houses (Minerva Press, 2000). Kadi, an architect from Sidhpur but based in Chennai, is actively involved in conservation initiatives for Sidhpur and can be reached at [email protected].

Sidhpur

Vohrawad

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.