“Everything can change in an hour,” I think, as our car

Monsoon clouds obscuring the snow-capped peaks clear sporadically in brief teasers. Jorepokhriis at an altitude of around 7,000ft. The temperature dips gently at first, as does my alertness; it has been a long and sleepless journey, and I am now so languid, my eyelids begin to drop and the mind trips out, surfacing intermittently to soak in the cloud-soaked, shape-shifting landscape, with its alpine forests, terrace farms, tea gardens and green valleys.

The route traverses the mostly open Nepal border at points and reenters India several times; ‘countries’ begin to seem like little more than words on a map. At some points, the road itself forms an open border; cross it, and you are in a different country. By the time we reach the Jorepokhri Tourist Lodge, visibility is down to 10ft or so, and it is raining incessantly. There is a vague plan to go birding. Shishir, my guide and new travel companion works with Help Tourism, an NGO and ecotourism operator in the region. “So we set off at 5am, tomorrow?” he confirms.

The rain looks like it’s here to stay. I am not a morning person, and am out birding for the first time, still finding the word itself bizarre in itself. After this, I go home and tell people that I ‘birded’ last week? It had a rather odd ring to it.

“Sure,” I reply, wondering what I have gotten myself into.

As expected, the morning turned out wet, but we got to see some fidgety warblers, whistling thrushes, babblers and a few tits and a lot of khalij pheasants. Shishir seems to be good at bird impersonations, whistling at them in a bid to lure them into conversation. This he manages with some success whenever the impersonation comes out right. However, when they come out noticeably strained or windy, the bird, suspecting an impostor, stops responding till he gets it right again.

The weather, combined with my lack of birding equipment, ensured that I didn’t spot too many birds, but I learnt that the harder it is to spot a bird, the more meditative the experience becomes, because it forces the birder to thwart all distractions and point the arrow of attention at the sounds and movements of a fleeting bird. I was rationalising my failure at birding into high-altitude Zen.

After digesting my dose of profundity, it was time to explore Sakhyapokhari, a small town with good mountain views. Sakhya is a great place to shop for goods smuggled in from across the nearby Nepali border, and like in Nepal, bargaining is the norm — and it comes in an enjoyable blend of playfulness and bonhomie. There are almost no tourists in Sakhya, which by itself makes it an enjoyably authentic experience.

The following morning, we left for Lava, the gateway village to the Neora Valley National Park, and stopped en route at Tinchule, a ‘model village’ where Help Tourism and the World Wildlife Fund have an ecotourism project, and visited a huge citrus fruit orchard in the nearby Baramangwa area.

The rain and cloud cover lend Neora Valley’s mixed forest and its giant towering trees a more exotic character, making each moment different from the last. However, the monsoon makes trekking in these parts difficult by populating the walk with bloodsucking leeches.

My guide also took me to Kolakham, a charming little village of Nepali Rais who have embraced a faith that forbids the consumption of alcohol, garlic or meat. The villagers here are extremely friendly. Birds and animals here have gotten used to the idea that humans are harmless, so they are relatively unafraid of birdwatchers and wildlife photographers. Kolakham is on the fringes of the national park, and offers great views of the mountains. It seems like a great place to belong to, if you don’t mind the lack of electricity and the 12km walk to the closest school if you’re a child.

Lava, the once idyllic village that is used to access the Neora Valley, is now overcrowded, even in off-season, with concrete hotel buildings dominating its spread. But if you venture out under the cold cover of twilit fog and light drizzle, Lava still radiates some of its old cluttered charm.

A three-hour drive from Lava took me down to Gorumara National Park, close to the Himalayan foothills. This was a return to the hot, humid plains. It felt strange to be sweating again, losing my daily access to momos, seeing signboards in Bengali and not having passersby pan grins at me.

After checking in at the new ecotourism resort in the park run by the forest authorities, painted in an atrocious pistachio green, I began to plan the day. The banner above a black plastic tank on a tower read ‘Gorumara Eco Village’. The tank was leaking profusely.

The chairs and tables were flimsy plastic, to go with the linoleum flooring and polyester curtains. These guys needed some help with the décor. But what they lack in finesse, they make up for with location and good intentions. The resort employs the poor Udia and Udaas adivasis from the adjoining villages, and also sells their agricultural produce, meat and crafts to tourists, thereby generating income for them.

After a satisfying lunch of fish harvested from the nearby pond, an Udia guide took us on a tour of his quiet village. Houses here are built on wooden stilts, and so escape the ire of rampaging elephants. A fisherman was sorting his catch of fish, snails and crabs, while women were drying chillies and grains. Children raced around on oversized bicycles, obviously shared with grownups, trying to enter every photograph.

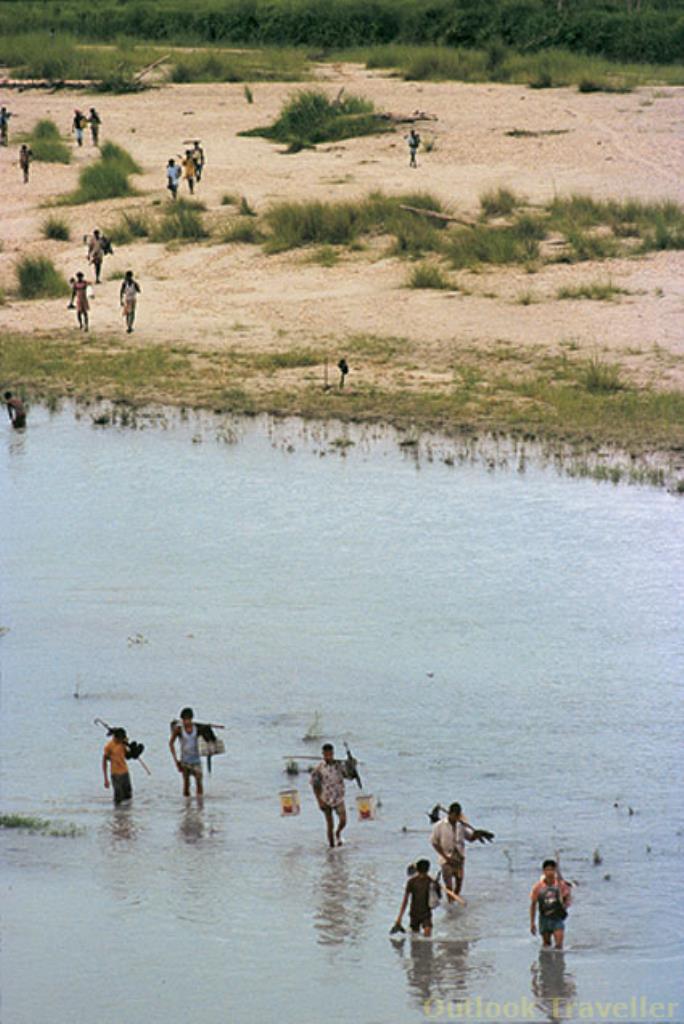

An evening trip to the watchtower overlooking the grasslands and floodplains followed. We didn’t get to see any one-horned rhinos or gaur (Indian wild bison). I was disappointed, because Gorumara is supposed to have sizeable populations of these large herbivores. But what did transpire about 1,500m away, surprised even the Range Officer when I told him about it later: a file of some 10 elephants and their calves began to cross the river, stopping to drink, play and spray themselves with water, and then moved on. Bigger tuskers seemed to play coordinator, stopping to check if any herd members had been left behind. Then, another set of 10 appeared, and then another 28 or so… Range Officer Bimal Debnath explained that migrating elephants normally travel in herds of 10, but sometimes when food is abundant, several herds can travel together to socialise and facilitate genetic exchange. Many elephants remember acquaintances from other herds and stay in touch over distances.

The night presented another surprise in the form of a light show by hundreds — possibly thousands — of fireflies hovering close to the ground. The resort turns down artificial lights at night to let the glitter bugs take centre stage.

The following morning, we went on an elephant safari through the core jungle. An elephant can go where vehicles and humans can’t; but my juvenile pachyderm, cute as he was, could never keep still when I needed to shoot pictures. None-theless, along with the mahouts, he managed to show us a big, brown buffy fish owl till it was chased away by a little long-tailed drongo; some sort of huge gliding stork and a gaur 100m away. When we circled him and went around for a closer look, we found a whole herd of around 10, surrounded by egrets. Having found what we wanted, we moved on once the herd disappeared into a thicket.

Suddenly, a huge lone bull galloped out from the foliage, snorting, bellowing and ready to attack the motley ensemble of animals that we were. He was apparently the leader of the herd, calling our bluff.

This was not looking good.

Armed with massive horns, he was more aggressive and probably even stronger than our young elephant. The gaur was perfectly justified; we were, after all circling his herd like an ambush predator. Our mahouts were quick to respond. They backed off, making grunting noises to dissuade him from launching a preemptive strike. We were safe again.

On reaching the riverside, we found fresh footprints of one-horned rhinos. We had just missed them. This time I didn’t complain.

The information

Characterised by high peaks, alpine forests, abundant biodiversity and quaint villages, the Darjeeling Hills are historically, culturally and ethnically closer to Nepal, Sikkim and Bhutan. But British colonial annexations and treaties during the Raj brought this part of the Eastern Himalayas into the state of West Bengal, in which it continues to exist as a somewhat autonomous region.

Getting here

Bagdogra is the main airport for the entire region of the Dooars.

By air Indian and Jet Airways fly from Delhi to Bagdogra; fares begin from around Rs 5,800 for one-way economy class. There are also flights from Kolkata; one-way fares begin from Rs 3,300 on Indian. Siliguri, 12km east of Bagdogra, is the gateway town, from where buses, jeeps and taxis head to the hill area. It takes approximately three hours to travel by road from Bagdogra to towns like Darjeeling and Kalimpong.

By rail New Jalpaiguri is the railway station that’s closest to other towns in the region. BY ROAD State-run and private buses also go to Siliguri from Kolkata and Patna. For Gorumara National Park, the nearest railway station is Madarihat (7km). Other accessible rail stations are Siliguri, New Jalpaiguri, Alipurduar and Cooch Behar from where one can hire a jeep/car to Lataguri, the gateway to the park (about 75km from Siliguri).

Getting around

The Jorepokhri Salamander Reserve is approximately 17km from Darjeeling town and 1km from Sakhyapokhri. Jeeps and buses regularly ply between Darjeeling and Sakhyapokhri. Tinchule village and Badamangwa are approximately 33km from Darjeeling and offer home stays and ecotourism packages. Neora Valley National Park is accessed from Lava, 34km from Kalimpong town. Buses, taxis and share jeeps are available. A 12km drive/trek down Neora Valley leads to Kolakham village. Public transport is not available for this stretch.

The organisation

Help Tourism is a major ecotourism operator that focuses on community benefits and conservation through its projects. The outfit organises wildlife trips in North Bengal (as well as in the Northeast). They will draw up an itinerary for you — a birding-focused one, if you like — and they can arrange for your accommodation at the Jorepokhri Tourist Lodge, at homestays in Baramangwa, Tinchule and Kolakham (approx. Rs 600 per day), in Lava and at the Gorumara Eco Village in the Gorumara National Park. An alternative for the last is to stay at the Gorumara Forest Rest House. To do this independently, you will have to contact the District Forest Officer at 03561-224907.

What to do & see

The six-day Sandakphu trek begins at Mane Bhanjyang, near Darjeeling, via the Singalila National Park to Sandakphu. There are stunning views of Kanchendzonga, Makalu and Everest.

Go on day treks in the Neora valley.

Visit orange orchards and organic farms at Badamangwa.

Raft on the Teesta River.

Visit the Buddhist monasteries at Darjeeling, Ghoom, Lava and Tinchule.

Take a tea garden tour in Darjeeling and Gorumara.

Shop near the Indo-Nepal border at Sakhyapokhari.

Dooars

Kalimpong

Neora Valley National Park

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.