“What is Art?” I ask myself as I watch bubbles erupt from one of Susanta Mandal’s

The Kochi-Biennale Foundation was set up in 2012 by artists Bose Krishnamachari and Riyas Komu primarily to host the biennale, but also to conserve and promote art in the country. The first biennale, held in 2012, was curated by Krishnamachari and Komu, and its focus was on the Muziris, the ancient urban seaport, which drew traders from all over the world as long back as the 1st century CE, but mysteriously disappeared under the sea in the 14th century. This year’s biennale, titled Whorled Explorations and curated by artist Jitish Kallat, aims to connect the past with the future, and the terrestrial with the celestial. It features 99 artists from 40 countries, and their artworks are displayed in seven venues across Fort Kochi and Ernakulam.

The previous day, when Jitish took us around the venues of the biennale, he said, “Artworks have their own energy fields and their own feelings and their own identities. Especially in a place like Aspinwall House [the main venue of the biennale], where there are 69 projects, there clearly had to be an unfolding of one experience into the other, because for me it is important that the biennale is seen through the afterimage of the previous work. In a way, it’s a stacking of these afterimages starting with Charles and Ray Eames’ Power of 10, which I hope will resound a few rooms down.”

Jitish’s plan seems to be working. Earlier that same day, I had been mesmerised by the very same film essay — it starts with a couple picnicking in Chicago and then it zooms out of them by the power of ten every ten seconds. Soon the Earth, the Solar System and the Milky Way are specks and you are transported to the very edge of the known universe. And then it starts zooming in by the power of ten every ten seconds. It reaches a point on the man’s hand and continues zooming in until you’ve seen an infinite universe within and outside you. Stunned into silence and hungover from that visual feast, I had walked into the next space where everything seemed to make sense — Aram Saroyan’s minimalist poetry suddenly seemed coherent — albeit for a few minutes.

I was back in Aspinwall today, determined to see what it was that so many could in some of the abstract art on display. But before I spent hours racking my brains, I just had to visit my favourites — Nayar, Rahal and Locke. Parvathi Nayar’s The Fluidity of Horizons includes a suite of drawings and a sound installation that draw inspiration from the Malabar coast’s history. I stare with wonder at the drawing of an oversized peppercorn looming over stormy waters, also watching the artist’s shy little daughter’s reflection in the painting. After a fleeting conversation with the little girl, I walk past a few exhibition spaces to see Hew Locke’s Sea Power, a room full of exhibits made entirely with black cord and beads. The imagery is fantastic — you see a coloniser (probably Vasco da Gama) and you see lines of black beads running down from the exhibits, perhaps suggesting decay, or like the author proposes, maybe it is just a reminder of the fact that our present is a consequence of the years of colonial rule that Vasco’s first journey brought with it to the subcontinent. I walk further on to The Laboratory — a large sea-facing room covered in white tiles from floor to ceiling with a sanitised, hospital-like air to it. Inside is Sahej Rahal’s Harbinger, a collection of structures and objects covered and made with clay and hay, which made you think of evolution, of birth and death, and of the past and the future. It comes together perfectly in that hospital-like atmosphere, which could both create and destroy. I leave Aspinwall slightly disappointed — unfortunately, Nikhil Chopra’s live performance La Perle Noire: Le Marais and Anish Kapoor’s Descension would not be in place (like some other exhibits at the biennale) until after I had left Kochi.

The next day, after spending an hour with the who’s who of the art scene at the BMW Art Talk and brunch, I visit Pepper House, a 5-minute walk from Aspinwall. The exhibition spaces here are set around a courtyard, at the centre of which is N.S. Harsha’s Matter. I grab a cooling sarsaparilla sherbet from the café, and walk towards the sea to take another look at Gigi Scaria’s Chronicles of the Shores Foretold, to see whether I could finally appreciate it. An ironwork frame holds a steel bell above a pit filled with water, and from the bell, through holes on its surface, sprouts water — a symbolic puncturing of time, according to Scaria. I cock my ears and move my head from side to side, trying to make sense of it. Then I leave.

A short drive from Pepper House takes me to David Hall, where I meet Suresh Jayaram, founder of the 1 Shanthi Road studio gallery in Bengaluru. Suresh tells me that David Hall is where Hortus Malabaricus, the botanical treatise on different species of medicinal plants, was written, and adds, “The Dutch came here and collaborated with the local people to get specimens of medicinal plants, which they illustrated for the encyclopedia.” Suresh gives me insights into the biennale and Kochi as the burgeoning art capital of the country and tells me of the financial worries that have wrought the biennale since its inception. Apparently, funding from the Kerala government has not been adequate and the organisers were still raising money to get some works of art in place. This definitely explained why the venues are not yet ready, even though it’s the day after the exhibition has opened to the public. And then I remembered what Tate director Chris Dercon had said at the art talk: “… after all, art is a work in progress.”

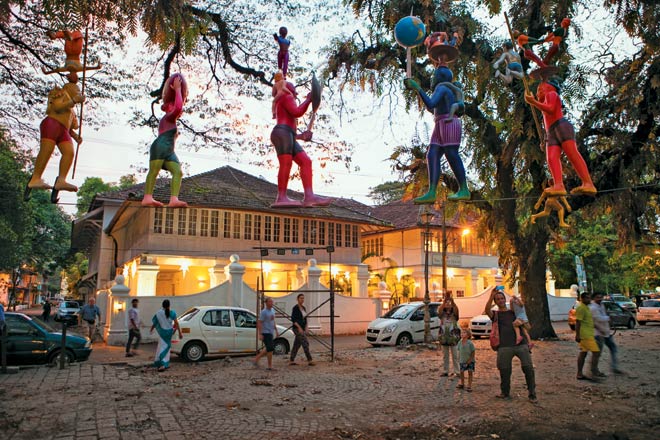

My mind is filled with more questions than I had started with. I walk down the streets surrounding Parade Ground towards the Vasco da Gama Square. Along the way, tiny stalls with quirky fridge magnets and wood and coir knick-knacks catch my attention. A random bystander greets me with a loud “Muziris Biennale!” and I respond with a smile. I walk on to the square to find colourful figurines, four or five feet high, being balanced on a tightrope. On a chair not too far away is the elderly Gulammohammed Sheikh watching his Balancing Act being put into place. I turn to him for an explanation, but all he has to say is, “Find your own. Isn’t art what you make of it?” My questions are answered.

The Kochi-Muziris Biennale opened on December 12, 2014 and will run for 108 days till March 29, 2015. Tickets (adults Rs 100, children Rs 50) are available at Aspinwall, Fort Kochi and Durbar Hall. The guidebooks available at the ticket counters are perhaps the best navigation tools for the biennale. To make donations and for more information, see kochimuzirisbiennale.org

Durbar Hall

Fort Kochi

Kochi-Muziris Biennale

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.