The peregrine falcon is the fastest bird in the world. It can dive at speeds of over

At the Abu Dhabi Falcon Hospital, concerned men in white kanduras alight from SUVs, falcon on arm. The birds are almost thought of as family members in these parts, and they even get flown to Central Asian countries for hunting (provided they have a passport and visa). The hospital’s founder, Dr Margit Muller, explains the fuss about falcons: they are one of the few remaining links people here have with the old Bedouin way of life, in which falcons were invaluable for hunting scarce game in the desert.

Just fifty years ago, Abu Dhabi was little more than a fishing village by the Persian Gulf. Today it is the sprawling capital city of the UAE, amidst a cluster of islands connected by multi-lane motorways; it is a tirelessly landscaped green oasis in the desert; it is an urban spectacle of diverse, occasionally disjoint, contemporary architecture. The lubricant for this blindingly quick turning of the wheels of material progress is natural oil, a tenth of the planet’s known reserves of which lies beneath Abu Dhabi, and which has been put to work only in recent decades. Abu Dhabi is now a hub of commerce, with close to eighty percent of its residents being expats. So far, Abu Dhabi has lagged behind frenetic Dubai in the matter of tourism, but it is now rapidly catching up. To showcase this and spread the word, the Abu Dhabi Tourism and Culture Authority is hosting three journalists from India, which is how we happen to be here.

Wherever we look, this is a place of superlatives — Abu Dhabi obviously takes pleasure in having things that are the biggest, richest, longest, fastest. The Capital Gate building, thought of as the leaning tower of Abu Dhabi, holds the Guinness record for the farthest leaning building in the world. The hotel we’ve been put up in — the Emirates Palace — holds the Guinness records for the most expensive Christmas tree decoration ($11 million), the most expensive shot of cognac sold (40 ml for $2,226), and has applied for the honour of possessing the longest single-piece hand-woven carpet (very long, and hanging on a wall).

The 7-star Emirates Palace, completed in 2005, is now apparently only the second most expensive hotel ever built, but I have no trouble giving it the status of the most opulent place I have ever set foot in. Tons of marble, gold-plated fixtures, Swarovski chandeliers, patterned tiles, domes, intricately-worked carpets and miles of rich fabric are tastefully tossed off like they’re nothing. And this is kept up over sixty acres of centrally air-conditioned interiors. It takes a full ten minutes of walking into cavernous hallways under rotundas and along interminable corridors to reach my room from the hotel’s entrance (more when I lose my way), and I can’t help being reminded of an old video game called Prince of Persia that involved endless jogging along the corridors of a palace, except that the computer graphics of the 90s pale in front of this reality.

My room is reliably plush (it is surprising how quickly one can take luxury for granted) and has a balcony-view of the sea. The greatest joy of the room is the fact that everything in it works exactly as it is supposed to — a shower with an instantly responsive temperature knob, lights that dim or brighten at the touch of a button, towels, napkins and toiletries exactly where I tend to reach for them. Then, there’s a fiendishly proactive housekeeping service that pops in whenever I pop out and replaces anything I’ve as much as touched or moved. After realising this, I try to reposition things exactly as they were when I don’t want them replaced, but the stratagem never works. I begin to imagine someone with a PhD in housekeeping looking at my childishly re-folded towels, laughing indulgently and replacing them with freshly laundered ones. One day, I happen to leave tossed across the unmade bed a strip of Kannada newspaper inserted by the istriwalla while folding my shirt. When I return, the bowl of grapes that I’d sampled has been replaced by succulent golden plums, a small box of chocolate has appeared on the bedside table, and the strip of newspaper is exactly where I’d left it, but now on a perfectly made bed.

The hotel has a kilometre-long private beach, helipads, and a marina from which we take a speed boat ride. The sea happens to be a particularly good place to take in the contours of Abu Dhabi. We bump along beside the Corniche Road, the eight-kilometre-long waterfront area with buildings and monuments arrayed in the background, then to the fish market by which float dhows with bunches of grill nets near their tail.

Outside our hotel is a gigantic hoarding with the visage of Sheikh Zayed, considered the father of the UAE. He was the emir of Abu Dhabi and the moving force behind the formation of the UAE, of which he was president for over three decades. His photographs and portraits are ubiquitous in Abu Dhabi, and every other road, institution and monument seems to bear his name. But of all the things named after him, the grandest must be the Sheikh Zayed Mosque, envisaged by him and finished in 2007, three years after his death. He now lies buried here. The mosque is a sprawling, blinding-white marble complex of minarets and domes. Floral motifs are inlaid in the courtyard tiles and wind up walls and pillars in relief. The pillars are modelled after palm trees and end in swells of gold. In the main prayer hall dangles the most spectacular of the several crystal chandeliers in the mosque. Beneath it is what is supposed to be the world’s largest hand-knotted carpet (a little over 61,000 sq ft). The walls are covered with Koranic inscriptions and dense arabesques that swirl in and out of more defined geometries, vast cosmic doodles that humble and reassure.

The driver of our car is a fatherly man in his fifties from Pakistan, Saeed. “Tell me something,” he says, as we pull up outside the mosque. “Some people say this looks just like the Taj Mahal. Is it true?” He’s wanted to visit Agra for some time, but it’s unlikely that will happen any time soon. “There was some hope with Vajpayee-sahab and Nawaz Sharif, but things are looking difficult again.” Yes, we tell him, the Sheikh Zayed Mosque looks more or less like the Taj Mahal.

On Saadiyat Island, a short distance from Abu Dhabi city, there’s a massive development drive on to create a business, leisure, residential and, above all, cultural hub. The guide at the Manarat Al Saadiyat visitor centre shows us around some works of art at the UAE Pavilion, including, proudly, a wall of graffiti inside the gallery. It strikes me then that I’ve seen no graffiti at all on the streets — perhaps a benevolent and well-off monarchy houses no malcontents. Saadiyat aims to have, according to Abu Dhabi tourism, “the world’s largest single concentration of premier cultural assets.” In the next few years, a Louvre Abu Dhabi and a Guggenheim Abu Dhabi will come up here.

The food in Abu Dhabi is eclectic, as befits its large expat population. We eat in a variety of restaurants — Lebanese, Indian, from enormous buffets that contain all the world’s major cuisines. We sample traditional Emirati food at one of the Al Dhafra restaurants. The manager Abdel Rehman guides us around local preparations: a spiced chicken sludge called margouga; rice and oil eaten with a mince of shark called gesheed; fish curries; biryanis; Um Ali, a bread pudding in milk with nuts; khabissa, semolina flavoured with saffron and dried fruits.

Date palms are everywhere, some with nets below the fronds to catch the fruit. Dates are everywhere too, and in more varieties than I believed existed. They are consumed here as snack, appetizer, as sweetener with Arabic coffee, as dessert when coated with chocolate. The fresh fruit of the date palm, plucked before it dries into dates, is a revelation to me — a yellow, ber-like fruit, crisp and only pleasantly sweet.

“Everything is bigger and badder on Yas Island,” says the Canadian sales manager who is showing us around the Yas Links golf club, our first port of call on the island. I can’t help being a little sceptical, given that we haven’t seen anything so far that hasn’t been big. Then I go to the restroom and get lost in a maze of wood-panelled changing rooms and lockers. On the island is also the Yas Marina racing circuit, gearing up for the Formula One race in November. Not far away is a massive dune of twisted tubes — the Waterworld park, its theme referencing an earlier time when this area was known for its expert pearl divers. There’s something surreal about seeing so much water in the middle of the desert — pools, fountains, crashing cascades. I ask and am told it’s all desalinated seawater. Outside the water, it is so hot in the sun that people relax in air-conditioned tents between rides. Earlier this year, Yas Waterworld joined other water-parks in an attempt to break the record for the world’s largest swimming lesson. Which must count as pretty big and bad considering we’re in a desert.

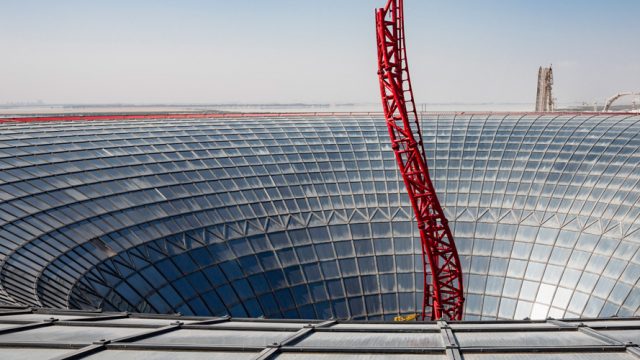

Ferrari World, on Yas Island, is the world’s largest indoor theme park. Even in Abu Dhabi, where powerful cars roar past all the time, it’s breathtaking to see so many sleek and brutal Ferraris from over the years. The place is filled with immersive rides: one takes you across Italy on the trail of a Ferrari; others spin and swivel you around in their seats to convey the effect of high-speed driving. But the centrepiece here is where the long choral shriek emanates from at regular intervals — the Formula Rossa, the fastest roller coaster in the world, reaching 240 kilometres per hour. The ride only lasts a little less than a minute, an insane hurtling that’s over so quickly there isn’t even time to be properly scared. It ends, and you get off glowing and bewildered, knowing that was fun but wondering where you were and what just happened.

The information

Getting There

Etihad, Air India and Jet Airways fly direct to Abu Dhabi from Delhi (Rs 26,000 onwards). Abu Dhabi can easily be combined with a trip to Dubai, 150km away, and Dubai return tickets are often much cheaper.

Tourist visas to visit the UAE can be obtained through the airline the tourist is flying, the hotel in which the tourist has reservations, or a local sponsor.

Getting Around

Abu Dhabi has a round-the-clock bus service and taxis are easily available ($0.5 per km).

When to go

Abu Dhabi is at its most pleasant in the winter months (Nov–Apr).

Where to stay

The 7-star Emirates Palace Hotel is a landmark in Abu Dhabi (West Conriche Road; kempinski.com). The Viceroy at Yas Island is a stylish contemporary 5-star and overlooks the Formula One circuit (viceroyhotelsandresorts.com). The Crowne Plaza at Yas Island is a very well-appointed 4-star hotel (ihg.com).

What to do

The Abu Dhabi Falcon Hospital provides a unique insight into the culture of the region. Guided tours available (falconhospital.com). The Sheikh Zayed Grand Mosque has free guided tours (szgmc.ae). Heritage Village is a recreation of an oasis village (near Marina Mall, Breakwater; admission free). Walk along the Corniche or bike (hire one from Fun Ride Sports for $4 per hour; funridesports.com) or call an EZ Taxi ($4 per journey; call +971 56 145 4242).

For an overview of Abu Dhabi’s sights, take a Big Bus Tour (bigbustours.com). At Yas Island visit Ferrari World ($55 per adult; ferrariworldabudhabi.com), Yas Waterworld ($60 per adult; yaswaterworld.com), and the Yas Marina circuit ($33; yasmarinacircuit.com). Marina Mall is a landmark (Breakwater; marinamall.ae) and The Galleria is a newly-opened mall (Sowwah Square, Maryah Island; thegalleria.ae). Check out a souk at Central Market (centralmarket.ae).

Where to eat

For a taste of home, Angar is the excellent Indian restaurant at the Viceroy (Yas Island; +971 2656 0600). Lebanese Flower (three branches: Tourist Club, Khalidiya and Defence Road; lebaneseflowerrestaurant.com) is a chain serving satisfying Lebanese food in huge portions. Traditional Emirati food can be found at Al Arish restaurant (Mina Port; aldhafra.net).

The Abu Dhabi Tourism and Culture Authority (visitabudhabi.ae) is a valuable resource for planning a trip there.

Emirates Palace

Ferrari World

Saadiyat Island