The road whips back and forth through the sand. Switch backing abruptly upwards and then sharply again

I discovered the mellow stones of the Haret Jdoudna after an afternoon spent hefting sacks of rice and distributing Id gifts among the Bedouins in something I could only call the valley of stones. Madaba, the small town not too far from Amman and close to the Valley of Moab, has recently unearthed a clutch of Byzantine mosaics on a Roman street. And the Haret Jdoudna restaurant (+962-5-3248650; haretjdoudna.com) has a wall made from old Roman stones with a gently cascading fountain in the courtyard. The place is built like a nineteenth-century Jordanian house with a ‘souk’ selling local handicrafts for charity and, among other intriguing wonders, food.

Sitting by those golden stones in the afternoon sun you break bread and dip it into an infinite variety of dishes. Pickled eggplant with walnuts and garlic, crispy bits of pita bread with a mélange of vegetables, starred with scarlet tomatoes, rosemary, mushrooms and, of course, hummus. Mezze in Jordan, as in all Levantine cuisine, is served before large-scale meals, though occasionally you will find it at breakfast with its creamy, cheesy incarnations. Crumbs dot the wooden table and time seems to disappear as you loll against the cushions, breaking bread. Weathered wooden cooking utensils dot the walls on the side over the earthenware pots. Glasses of mint steeped in sweet lemon juice pass from hand to hand.

The wind that blows is the drowsy wind from the Levant, from the road to Damascus, from the hills all around West Asia, with not a hint of strife in it. It gently stirs the spread of mezze, both warm and cold, while the conversation floats to Lawrence of Arabia and banquets of sheep heads, their eyes a delicacy. “Mansaf,” someone says wisely, referring to banquets held by sheikhs with a sheep’s head added to a pile of rice and pine nuts to show their wealth of herds. There was logic to it, sacrificing a sheep for every one hundred, though the ladies were doubtful about the eyeballs and insisted Lawrence had exaggerated.

Sheep dotted the ridges along the Desert Highway. From time to time modern caravanserais popped up to break the monotony of sand and potash plants. The serais were sheer eye candy, built around courtyards with green potted plants in the middle and striped sofas in cosy niches where people could sit back and sip mint tea in glasses — black tea, not the green Moroccan variety — or bargain for souvenirs. And for the fact that at 7 Jordanian dinars a glass (JOD 1=Rs 78), one could have said the tea was almost highway robbery!

The hills of Petra wore olive tree spikes, like strange rock-star headgear. Some of the trees had seen Roman sandals march past. Plunging past the Indiana Jones souvenir shop and dodging racing buggies, donkeys and horses, I entered the old city of Petra. Dust, Nabataean cobblestones and the famous treasury that opened out through the drama of the dark curving rock walls looked exactly like a film scene. An hour later, deeper into the stones and caves of the past and obstinately refusing donkey rides, it was time to recharge the batteries. For some time there had been an infiltration of restroom signs and souvenir shops with four walls instead of planks on the sand, selling stuffed Rajasthani camels. There was a coffee shop run by a New Zealand woman who had married a Bedouin and written a book about it, but the situation demanded more than coffee. The Basin at the Crowne Plaza Resort (+962-3-2156266) offers an atmospheric buffet lunch on the patio with a view of the sandstone rocks. The spread starts with mezze baba ghanoush and hummus and goes on to chicken, lamb and smoked fish followed by lavish desserts of the Continental kind, all for JOD 17 a throw. A waiter came to chat in between shifting dishes and said he was being sent to train in the Marriott Mumbai.

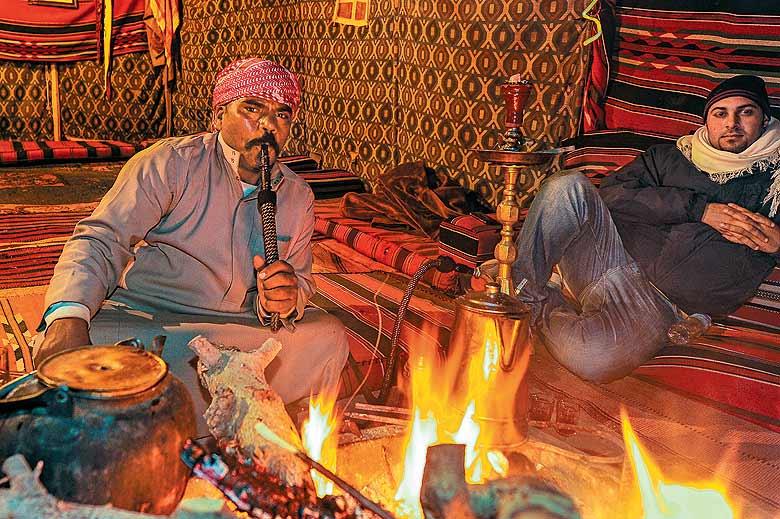

At the Petra Marriott hotel (+962-3-2156407, marriott.com), however, after a day of tramping up and down the Nabataean sands and Petra’s rosy stripes, it was refuge from the cold winds in a red-and-black Bedouin tent by the pool waiting for a traditional dinner that took two hours to cook, buried in a cage underground with a lid and coals on top. Not the mansaf of sheep, but chicken with crisp, crackling skin that gave way to smooth simplicity, and rice and potatoes underneath, enough to warm your hands and stomach with on a cold desert night. The hotel threw in Arab robes for those inclined to dress up or requiring extra warmth — a polyester blend though, not camel hair, obviously designed for modern times.

At Karak Castle, history remembers Reynald de Châtillon who obstinately held on to the strongest of the Crusader castles, flung his enemies down the iceberg steep walls and plundered spice-rich caravans at will. Karak, however, is also making a name for the Kir Heres Restaurant (+962-3-2355595) where your tastebuds can run into Roman extravagances such as ostrich steaks for JOD 7. Draped kilims set the atmosphere and make it look more expensive than it is. Don’t be worried. If you’re not experimental, try the chicken cooked local-style with herbs — but yes, you might find it difficult to go rock climbing in Karak Castle afterwards!

Where chicken is concerned, the R&B Shawerma in downtown Amman (Abu Bakr as-Siddiq St Downtown, 06-4645347) has the customary man shaving a tiered pyramid of meat and putting the flaky shards into a shawarma wrap. However, most Ammanites will tell you indignantly that a shawarma is not take-away food and that these shawarmas are unusual. They are available in three comfortable fist-filling sizes — six, ten and twelve inches — with your choice of fillings (Chinese, chicken and cheese) and fries on the side.

On a clear day, from the villa near the village of Wadi Seer, around twenty-four kilometres southwest of Amman, you can see as far as the West Bank looking out over the river. The house, sprawled generously over the hills, rises up from its own olive groves. Inside, was Syrian furniture inlaid with mother of pearl, painted walls and arches, Syrian costumes dating from the 1940s in glass niches on the walls. It was like being in a museum except that it belonged to Rosemary, an American married to a man from the Jordan valley and they had been living here since the 1960s.

The actual activity was not upstairs amongst the antiques and upholstery but in the long room below. There, beside the piano and by the windows looking out on to the terrace was the table — a sizeable slab of wood groaning under an assortment of baskets and wooden dishes that covered most of the Levant’s culinary delights. Sesame and tomato kifte, teardrop-shaped lamp kibbeh with peanuts at its heart, stifado, slow-cooked beef stew rich with garlic, tomatoes and cinnamon…the air was warm with the scent of nutmeg. Facing the table was a row of pitchers and coffee makers dispensing honey, syrups and drinks of choice. An olive press could be seen lying among the rocks that bordered the swimming pool. In between mezze I tried to find a way to see the West Bank or the river or both. Rosemary said the hills reminded her of Tennessee as she offered me sesame chikki made with honey and a pomelo salad punctuated with ruby pomegranate that had been grown on her own farm.

The weather was verging on winter and pomegranate season was in full swing — the road to Jerash, forty-eight kilometres north of Jordan, was dotted with sellers waiting for passing cars to stop and bargain. Two hours down the road and you would be knocking at the Syrian border. Here, the hills were green and had a look of Mediterranean landscapes about them, which was presumably why the Greeks and Romans had built in Jerash. At the Jerash Resthouse near Hadrian’s Arch (04-6351437), I discovered breadcrumb salad, moist with olive oil and lemon juice and bits of walnut at another all-you-can-eat buffet, which was a steal at JOD 5. The issue, I thought, was a chicken and egg one — had the Italians stolen the recipe for their own breadcrumb pasta? Or had it come to the Middle East with Hadrian and Antony and the rest? No one had any answers to my question so I buried it in bites of tangy white goat’s cheese shinklish and sips of more green mint and lemon sherbet.

Honeyed sweetness is another side of Jordan, a trail of candied delights that would have seduced Antony. The Zalatimo Brothers were famous for their confections, and stilettos and blue eye shadow trotted in and out of their fashionable La Mirabelle café (Al Umaweyyen St, East of Abdoun Mall, Amman; 06-5681018, zalatimosweets.com), obviously the place for ladies who lunch. What was served after the waiters decoded my stumbling mispronunciations was the murtabak, which had been created in 1860 when the Zalatimo Brothers set up shop. Layers of flaky pastry with goat’s cheese or pistachios and cream or walnuts folded inside (JOD 2.5 filled, JOD 3 with pistachios, JOD 1.5 plain), served with a honey and sugar-water syrup. Infinitely light, far from cloyingly sweet and to be savoured perhaps in between perfumed whiffs of a nargileh. Other Levantine delights are not so easy on the calorie conscience!

Then there was Crumz, calorific, high-profile and the cake shop of choice for expats planning birthday parties (Abdoun, Amman, 06-5920102). Continental was very definitely the flavour of modern Amman matching the white villas with trees shaped into cylinders of green. Cupcakes, tombstone cookies for Halloween, sheep cookies for Id and cupfuls of tiramisu with generous sprinklings of coffee. Not that Crumz was into elaborately shaped cakes — technology had brought Jordan graphic edible printing which cut down on the cake moulding effort and left room for brilliant icing colours. The individual pastries flared magenta, red and pistachio-green, as brilliant as the sequinned tunics, lipstick and nail polish of the habitués.

Miles away from Jordan, in a bus carrying passengers to another airport terminal, my eye was caught by large glossy white carrier bags with a familiar logo. One I’d seen dominating the Amman Duty Free. People were bringing Id treats to friends and relatives in other parts of the Middle East. The Zalatimo Brothers had had the last word.

hummus

Jordan

Jordanian cuisine