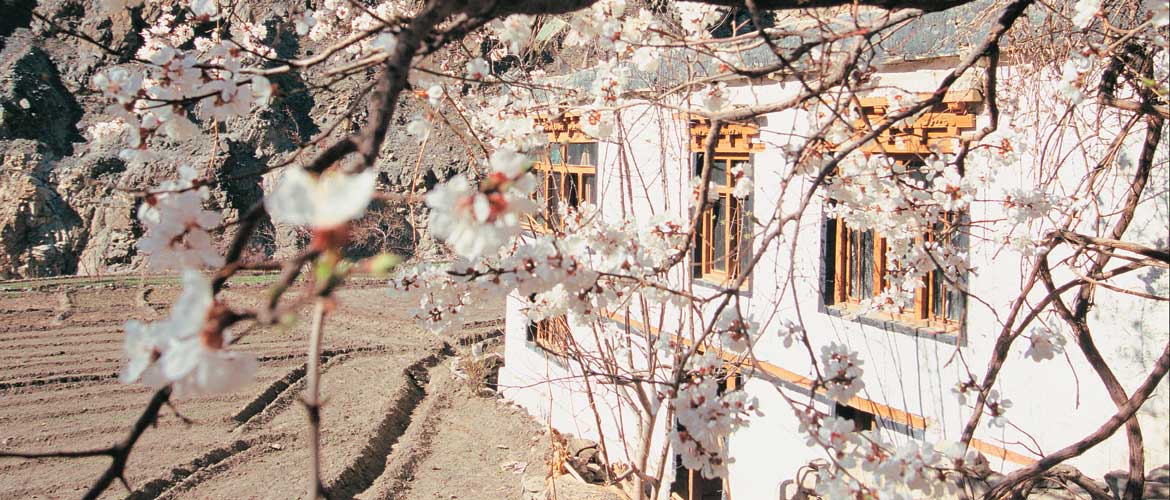

Winter is letting out the apricot trees. In little bursts. Brown bark merges with fine

Winter hasn’t gone entirely though. Getting out of the sleeping bag is an effort. The first light of the morning is peeping into our low-ceilinged room. My toes feel cold. Someone thrusts a small cup of pink, buttery gur-gur cha into my hands. It’s tepid, but the salty smoothness is warming. Clutching the tea in my hands, I bow through the door, into a dark corridor that lets out into a small dung- and straw-spattered courtyard.

Emerging from the confines of the house I feel I’ve walked into a cliff. Sheer walls rise along the edge of the narrow valley, and end in snow 2,000 feet above us. The valley can’t be more than 200 metres across at its widest. I’ve left the plains far behind, but the expectation of flat land still lingers in the mind’s eye.

It’s snowing in Garkhun today. A light powdery snow lifts off the ridges of the hills that surround us, and drifts gently on the breeze. Snowflakes the size of pin-heads melt the moment they settle on my bare arms. The snow comes in from my left, while the sun rises higher up the valley on my right. Ten minutes later there’s no sign of snow. As the image of snow fades, flowers of the apricot trees emerge. And then as the sun rises, the land seems to change dimension. The cliffs recede, revealing carefully terraced fields, surrounded by a crown of white and pink apricot trees.

Along comes Tashi, our host and surna (a shehnai-like instrument) player, who has just come back from a night of playing at a wedding and chhang-drinking. “How was the wedding?” I ask. He doesn’t look much worse for lack of sleep. His cowboy hat, though, is tilted at a slightly jaunty angle. That and the beautiful bunch of bright orange monthu tho flowers tacked onto the hat give him a rakish air. “Bahut achha,” he says, in a Ladakhi-accented Hindi, “aap aaj raat aa rahen hain?” And without waiting for an answer he disappears into the house. As I stand waiting for him to re-emerge, a few elderly ladies pass by. They’re wearing elaborate silver headdresses that support a deceptively real arrangement of plastic and monthu tho flowers. There are chains of jade and other colourful stones around their necks, and sheepskins to keep their backs warm. “Juley ji,” I say smiling. We exchange glances, trying to decide who’s more startled. “Juu-lley,” they lilt, and the lines on their weather-creased faces twitch into a smile.

Six sisters

We’re about 160 km from Leh. At Khaltse, 97 km from Leh, the road bifurcates, one branch heading south-east towards Kargil and onwards to Srinagar, the other branch following the Indus north-east as the river makes its way to Batalik. The Drogpas (‘hill people’), as they are derogatorily known, live in a group of six villages between Achinathang and Batalik. First on the road comes Hanu, once a Drogpa village, now more Ladakhi. Above Hanu lie Hanu Yogma and Hanu Gogma. Moving beyond Hanu you come to Biama, a quaint but dusty little village that abuts the road. Beyond Biama the valley becomes narrower, and if you weren’t looking out for villages you wouldn’t find them. Dah is just a signpost on the road, and a narrow path going uphill to your right — the village is a stiff 15-min uphill climb. Most don’t venture any further than this for till fairly recently the Army restricted access to these villages. To visit, you’ll still need to get a permit from the Deputy Commissioners of Leh and Kargil.

Garkhun, which lies about 4 km beyond, is indicated by a teashop. Darchiks is further down, on the left bank of the river; and a little further down, a half hour walk from the road, lies Gurgurdho, beyond Batalik at the border of Ladakh and Baltistan — a boundary that was fixed after the defeat of Jamyang Namgyal, the ruler of Ladakh, at the hands of Ali Mir, the ruler of Skardu, in the 17th century.

The Drogpa population is small — the population of all the villages put together would be under 5,000. But what they lack in numbers they more than make up for in colour and myth. The Drogpas, men and women, wear brilliant monthu tho flowers on their heads. The women weave their hair into long braids (six for unmarried women and eight for married), and wear elaborate head-dresses of silver that support entire floral arrangements. With that elaborate head gear, the Drogpas never really did have much chance of blending into traditional Ladakhi society.

The Drogpa ways

Legends about their private and social lives attest to their outsider (and curio) status — “The Drogpas don’t have the usual inhibitions about showing affection in public,” read one brochure rather solemnly, before going on to state that “men and women can be seen kissing in the open.” Others talk about them as a pure Aryan race, a legend that some of the Drogpas themselves are happy to play along with. “We’re pure Aryans,” Tashi had informed me in all earnest, “We came with Alexander from Rome.” I stared at him incredulously, scanning his face for signs of those much touted ‘high-cheekbones and blue eyes’. Another gentleman I met in Garkhun casually informed me that he remembered his grandmother worshipping Saraswati.

The reality, though, is a little different, and it’s easy to speculate about the origins of some of the myths surrounding the Drogpas. Their society was polyandrous till a generation ago. But apart from the primary wife, the younger brothers if they so desired could acquire additional wives too. Sounds a little lax, and might translate in the popular imagination into free love, but in reality served to keep precious land holdings from being whittled down. As for being Aryan, that found its inspiration in 19th century ethnographers who thought they’d landed at the end of the world, and needed to have something to tell the folks back home. They couldn’t have gone all that way to find a placid and slightly unwashed group of people with unexceptional noses! And somewhere down the line, Drogpas, shunned by the Buddhists of Leh for holding on to their animist deities, and looked down on by the Muslims of Kargil and Drass, figured that it made a lot more sense to be Aryan.

Not that Tashi seemed to be particularly concerned with all this idle academic speculation. He was fast asleep by the time I finished my breakfast of rice and moong daal. It’s eight by the time we get out of the house. Black-billed magpies flit from apricot tree to apricot tree, flying over the winding pebble-strewn paths that meander through the village, the blue of their feathers catching the light. The fields are empty — barley and turnip have been sown. Groups of men and women sit in the sun, by the apricot trees. Kids play hopscotch on the roofs of the houses. Women squatted by the water channel that winds through the village, dunking their dirty wailing kids in the frigid water. I found my own spot beneath the apricot trees and then sank into a stupor. It must have been all the chhang from yesterday afternoon’s wedding celebrations — memories of which were getting blurred and dreamy in the piercing heat of the sun.

Two glasses were the limit, I’d told myself. And it had started well enough. By the time we’d arrived at the house of the bridegroom Yountan Gyatso, an Army soldier posted in Siachen, the celebrations had started. A group of Drogpas were sitting in a cleared terrace field in front of the house and a slow dance was in progress. Six men moved in a closed circle in the centre of the clearing — their right hands raised, holding an imaginary flower. The older ones wore the ekta, the traditional maroon tunic made of sheep’s wool, while the younger wore Kal Klein jackets bought off the sidewalks of Leh’s bazaar. The musicians sat in one corner of the clearing — two of them played the surna and three played drums of different sizes. As I took my place amongst a group of young men sitting near the musicians, I was handed my first glass of cold barley chhang.

Magic of chulli and chhang

It was certainly of the very best vintage. The men were singing a song that rose and fell with every turn of the circle, and occasionally the people sitting around would join in for particular phrases, and so the song would drift around. So, how many songs were there in all, I asked Padma Tsering, the old surna player. “If we were to sing all the songs we know, we’d go on for 18 days and nights. There’s a song for every occasion.” When does the party end? “When the chhang runs out,” he said as someone refilled my cup. And refilled it, and refilled it. Later that evening, as I walked through the village I ran into Padma again, as he clambered up a hillside. He seemed a little lost. But seeing me he staggered across. “Budda ho gaya,” he said grimacing, staggering and clutching his knees, “Aap mere se kaal aake miliye, aaj chhang zada pi liya hai.”

After two hours the chhang-induced hangover begins to wear off. I wander back into the village. Going past the Sharingmo Lhamo Guest House (named after the lato, or the village deity) where we are staying, I bump into the nambardar (village headman) and a few other men, who are walking towards the gompa. There’s a large prayer wheel and a chorten outside the gompa, and as we circumambulate the two, the nambardar tells me that the lama is away. Moving on, I spot the Rigopa house, one of the oldest in the village, with windows the size of postcards, and three chortens representing Jameyon, Chador and Chandazig (all Boddhisatvas) outside one of the windows. A fair young girl peers at me as I pass by. “Can I come in?” I ask. “No.” I’m a little taken aback, given that most people we’ve come across have invited us to their houses. “Bahut puraana hai hamara ghaar, kala hai,” explains the girl shyly. It is very black — the wood and straw roof of the kitchen (which in most houses is also where everyone sleeps) is coated with soot from the hearth. A little baby swaddled in layers of blankets peeps out from a crib fashioned from a wicker basket. A plate of chulli (dried apricots) and giri (apricot) seeds is set before me as I peer at some ancient stone containers kept on the wooden shelves.

Tashi must be back by now. He is. And is holding the surna in one hand, ready to take off for the wedding ceremony at the girl’s house. Before we get there, we stop at the changra (village square), where a surreal dance unfolds. A line of women wearing their sheepskin cloaks makes its way to the centre and in the narrow glow of a solar-powered lamp repeats the dance of the previous afternoon. One slow step, one turn, one phrase at a time. And then we make our way into the house, which is packed to the last corner, with men, bawling babies, women chatting excitedly. The air is thick with smoke and the smell of chhang. I settle down in one corner and get talking to a quiet old man who is downing his drinks at an alarming speed. “We’ve come from Gilgit, that’s what our songs are about.” “Gilgi-t, that’s where Dulo, Melo and Galo came from,” he says, referring to a famous Drogpa migration story. “Gilgi-t.” It rolls off the tongue, and then echoes in the mouth. “Gilgi-t,” he says dreamily.

I’m getting claustrophobic in the little room, so I wolf down the pappa (boiled barley balls) and make my way to the roof. The night is freezing, and above me there are a thousand stars. On either side of me tower the silhouettes of mountains. A shooting star streaks across the sky. Lonely dim lights from stray houses flicker in the distance. And in the pale light of the waxing moon the apricot flowers look like mosaics of ghostly snowflakes. At night, the roar of the Indus is even louder.

The Drogpas might be shunned by other Ladakhis. There might only be 4,000 or so of them. They might depend on the Army for a livelihood. Their villages might be divided between Kargil and Leh districts and subject to different regulations. And Gilgit might be far away. Very far away. But below me the dance continues and the chhang never runs out.

WHERE TO STAY AND EAT

The Drogpa villages of Dah, Garkhun and Darchiks all offer stay, in family-run guest houses, tourist bungalows or PWD rest houses. In Dah, The Skybapa Guest House (Tel: 01982-228527; Mobile: 09419815534) is located in one corner of the village, and is surrounded by fields and apricot trees. The 6 rooms are basic. They charge ₹400 per day, per bed, and have three to four beds to a room. The Sharingmo Lamo Guest House, the only other place to stay in Dah, is higher up and offers lovely views of the village. They charge ₹200 per day per bed. There is no way of contacting Sharingmo (there are no telephones in any of these villages), but they can be booked through operators in Leh. The food at both guest houses is very basic, depending on what is locally available.

At Garkhun, you can stay at the recently opened Tayupa Guest House, arranged by your Leh operator. Rooms can also be booked at the Kargil Development Authority’s (KDA; Tel: 01985-232216, 232222) newly constructed Tourist Bungalow. Tariffs are around ₹200-250, for board only.

Darchiks has a PWD Guest House and a new Tourist Bungalow, both of which can be booked through the KDA. The KDA is setting up more tourist bungalows in some of the villages.

At Hanu, there are no stay options but you can try and ingratiate yourself with one of the villagers — they’re extremely warm and hospitable. Even if you get a place for the night, make sure you carry your own sleeping bags and some canned food with you. The villages are solar powered, but carry a torch and some candles. The few shops near the villages are poorly stocked.

Drogpa Village Walks

With Biama and Dah as bases, the Dah- Hanu region offers some idyllic village walks. No big gompas, no lakes. Just close encounters with the Drogpas, their homes, gurgling streams, apricots, barley, monthu tho flowers and gallons of chhang.

Day 1: Biama-Sanid-Lastience-Biama: Having arrived the day before at Biama and rested overnight at the Aryan Valley Camp (Tel: 01982-228543, Mob: 09419178890; Tariff: ₹4,900 all inclusive), head out to Sanid early next morning. The oldest Drogpa settlement Sanid has homes speckled on either side of a stream. Lastience is perched above Biama and affords an even better view. Be prepared for a steep climb though. Walk back to Biama before sundown.

Day 2: Biama-Baldez-Dah-Garkhun-Dah: The valley tapers beyond Biama, and Dah is just a few kilometres drive down the road. You could stop en route and cross a creaky bridge to Baldez, isolated on the right bank of the Indus. Dah sprawls along a verdant balcony in the gorge with another overhanging terrace of fields above it. Book into the Skybapa Guest House. Make the village of Garkhun your next stop. Spend the night at Dah.

Hanu village could also be the base for walks to Hanu Yogma and Hanu Gogma.

Bono-nah Festival

A legend of the Drogpa tribe has it that, long ago, gods and humans lived together in harmony until a young man seduced a goddess. The angry gods cast the tribe out, so they made their home in the remote Ladakhi village of Dah. For centuries, the Drogpas lived communally in a fort here, though they have now broken away and live in villages.

To see the Drogpa people relive their old glory, visit during the triennial night time festival of Bono-nah. This is when the tribe and its gods reunite. The lhabdagpa (‘master of the gods’) sacrifices a goat to honour the protector-deity, Shringmo Lhamo. He leads the villagers to the festival grounds. Here, he sings hymns, the men sing verses not meant for women’s ears and the women stroke the faces of onlookers with their flower bouquets. As the night progresses, the Drogpas drink chhang and the revelries get merrier. You can join in too if you make the trek up to Biama village in October 2016. Contact Himalayan Frontier Adventure (Tel: 01982-255345, Mobile: 09906980575) in Leh, who can organise a homestay, permits and transport for ₹28,000 for 3D/ 2N for two.

Chiktan Khar

Chiktan is a small sleepy village, nestled in the middle of snow-covered mountains, accessed by a lovely drive from Sanjak Bridge along the Sangeluma stream. As you arrive in the village, what you notice first are the lofty crumbling ruins of the 16th-century Balti fort of Chiktan — or the Chiktan-e-Rajikhar. The once majestic fort is now in ruins, its nine floors reduced to a few walls. When Nicholas Roerich painted it in 1932, it was in far better shape than it is now, but the view from the fort is still spectacular. The Chiktan Khar is 17 km south from Sanjak on the Khaltse-Batalik Road, and 11 km north from Khangral on the Srinagar-Leh NH1D. It is well worth the detour to visit this village with its mixed Balti-Ladakhi heritage.

THE INFORMATION

Location The ‘Dah-Hanu’ region is a string of villages inhabited by the Drogpa people, between Khaltse and Batalik. The villages lie along the Indus River, below the Ladakh Range

Distances Khaltse is 97 km NW and Batalik 183 km NW of Leh, respectively

Getting There All the Drogpa villages lie within a few kilometres of each other on the Khaltse-Batalik Road. From Leh, take the Leh-Srinagar Highway NH1D till Khaltse, 97 km away via Patthar Sahib, Nimmu, Basgo, Uleytokpo and Nyurla. At the Khaltse checkpost, leave NH1D, which crosses the Indus to the left, and take the bifurcation to the right, towards Batalik. The river is your companion the entire length towards the Drogpa villages between Achinathang and Batalik. It’s possible to get a bus from Leh all the way to Dah (₹200), but the 162-km journey takes about 6 hours, is fairly uncomfortable and the buses are infrequent. The only alternative is to hire a car from Leh to take you there. A two-day round trip from Leh to Dah costs ₹7,000. If you’re planning to keep the car for more than two days, be prepared to shell out a waiting charge of ₹1,800 per day (includes 80 km per day)

Permits You need a permit to visit any of the Drogpa villages. For Dah, Biama and Hanu, permits are issued by the Deputy Commissioner, or Chief Executive Officer of the Ladakh Autonomous Hill Development Council, Leh (Tel: 01982-252010), and for Garkhun and Darchiks from the Deputy Commissioner or CEO, LAHDC, District Kargil (Tel: 01985-232216, 232222). But it’s best to leave the permits (₹500) to your travel operator

Operators Himalayan Frontier Adventure (Mobile: 09906980575) in Leh arranges homestays at Dah. They also offer a 2N/ 3D package to Dah for ₹18,000 for two people (all inclusive). Dreamland Travels and Tours (Mobile: 09858060607) charges ₹14,000-15,000 for 2N/ 3D

ROUTES AND DISTANCES

Leh to Batalik 183 km

Leh to Khaltse: 97 km

Khaltse to Skurbuchan: 26 km

Skurbuchan to Achinathang: 14 km

Achinathang to Hanu: 9 km

Hanu to Dah: 16 km

Dah to Garkhun: 4 km

Garkhun to Darchiks: 7 km

Darchiks to Batalik: 4 ½ km

Darchiks to Grugurdo : 5 ½ km

India

Ladakh

Jammu Kashmir & Ladakh Guide