Ladakh is a high-altitude plateau at India’s northern frontier, bordered by PoK and Tibet. Its

This could be Tibet. The vast land, dry and desiccated, swells and billows into great tiers of snow-crested peaks. Arching over it is a sky, pure blue, benign, sheltering. The river bisects the floor of the valley. In summer it is a sullen grey, silt-laden, sometimes turning to violet. In autumn, the Indus is at its most graceful: turquoise and aquamarine waters weaving through golden banks of poplars and willows. Flat-roofed, white-washed homes rise above the bright green fields along the river, oases in this cold desert. Crumbling old monasteries perched on rocky crags command the barren, empty vistas. Dominating Leh from its vantage on the northern crag is a diminutive Potala. In the late afternoon the wind picks up, riffling the prayer flags, carrying snatches of the deep-intoned homage to Manjushri. And yet, an incongruous note is struck by the welcoming banners of Jammu and Kashmir Tourism, for what possibly could this facsimile of Tibet have to do with the Kashmir Valley?

“Nothing,” growled a Ladakhi politician once, “except an accident of history.” The ‘accident’ to which he refers is the conquest of Ladakh, once an independent kingdom of western Tibet, in 1834 by the Dogra rulers of Jammu. Twelve years later, pleased by the successful military intervention by Raja Gulab Singh, which enabled an English victory over the Sikhs, the British rewarded him with the invaluable gift of the Vale of Kashmir. This welded the raja’s disparate regions of Jammu, Ladakh, Baltistan, Gilgit and finally Kashmir into the kingdom of Jammu and Kashmir, which later became the political entity under dispute between India and Pakistan in 1947. Let us be grateful that Ladakh landed in India’s lap, for it could well have gone the way of its neighbours in western Tibet. For saving it from such horrors we have but one man to thank: Zorawar Singh.

Dogra General Zorawar Singh

By all accounts, General Zorawar Singh was a bit of an adventurer who fancied himself to be a military genius — an often fatal combination. Gulab Singh, an energetic ruler of great cunning, bided his time as a fawning vassal of the great Lion of Punjab, Ranjit Singh. The Sikh Emperor had acquired Kashmir in 1819, and found the shawl industry suffering because raw pashm from western Tibet was being channelled by Ladakhi traders to the plains of Hindustan along a new smuggling route through the British territories of Kinnaur and Spiti, in today’s Himachal Pradesh. Gulab Singh’s ostensible motive to send Zorawar to attack Leh was to bring the Ladakhi monopoly on the pashm trade under Ranjit Singh’s control. If, in the process of serving his master he were to acquire further territories, thought the raja, who should mind?

Certainly not the British, punctilious about their agreement of non-interference in Ranjit Singh’s affairs, much to the chagrin of the Gyalpo (king) of Ladakh, Tsephal Namgyal, who had sent many desperate messages for help. Faced with the well-trained force of Zorawar that poured into Ladakh from Kishtwar and Zanskar, the hastily conscripted Ladakhi militia fought a losing battle. As winter set in, Zorawar made the Gyalpo a proposal: pay an indemnity of 15,000 rupees and we will retreat. While the king and his ministers jumped to the offer, his queen forced him to refuse. Zorawar was back with a vengeance in spring, driving the Ladakhis before him until he reached the Indus. The Gyalpo met him at Basgo, this time agreeing to pay not only 50,000 rupees as indemnity, but also an additional annual tribute of 20,000 rupees, while declaring himself a vassal of Ranjit Singh. For his pains he was deposed and his grandson, Jigmet Namgyal, all of eight years old, was made Gyalpo.

With Ranjit Singh’s death in 1840 and the Sikh Empire in disarray, Gulab Singh became a formidable power. At his command, Zorawar invaded Baltistan victoriously. He then turned his sights on western Tibet, the source of the pashm and the land of fabled wealth of the Tibetan monasteries. Heady with victory, Zorawar underestimated the difficulty of the invasion. He met his end in the unforgiving Tibetan winter, when his small expeditionary force, weak with cold, met with a punitive army of 10,000 sent from Lhasa by His Celestial Majesty, Emperor of China, who now considered Tibet his domain. Zorawar Singh’s fort still stands at the end of Leh’s Fort Road.

Early history

Ladakh was not always peopled by the Tibetan race. A Chinese pilgrim, Hui-Ch’ao, journeying from India to Central Asia in 727, speaks of the area inhabited by the ‘Hu’ people, or Indo-Iranians, who practised Buddhism and who were under Tibetan suzerainty. Surprisingly, unlike Ladakh, Tibet in the early 8th century CE “had no monasteries at all and the Buddha’s teaching [was] unknown”. Thus, the Buddha’s teachings did not radiate from Tibet outward to Ladakh. It was the proselytising force emanating from Kashmir that took root in Ladakh and then travelled east to Tibet. Kashmir had been an important Buddhist centre ever since the Mauryan emperor Ashoka extended his empire into north India in the 3rd century BCE, with close political, cultural and religious links with western Ladakh for over a thousand years.

One of the earliest examples of pre-Tibetan Buddhist sculptures in Ladakh is the rock engraving of Maitreya Buddha at Mulbekh on the Leh-Srinagar highway, dating to the 8th or 9th century. The highly detailed pectoral and abdominal muscles, the high-arching eyebrows and full cheeks indicate that the figure was hewn out of the rock by none other than Kashmiri artists. Other examples are the giant Maitreya and Avalokiteshvara statues near Drass in Kargil District.

Ladakh, Kashmir, Tibet and the bond of Buddhism

Ladakh’s history, from the Middle Ages to the 19th century, becomes intimately connected to that of Tibet. In the mid-8th century, Buddhism was having a hard time securing a foothold in Tibet, which was under the influence of the animistic Bon religion. The Tibetan ruler King Trisong Deutsen tried desperately to maintain Buddhism as the state religion, even inviting the Nepalese scholar Sankarakshita in an attempt to subdue his people. It wasn’t until the king begged for help from a yogi from Uddiyana (presentday Swat in Pakistan) that Buddhism established itself in central Tibet.

Guru Padmasambhava, it seems, flew to Tibet astride a tiger, and was unimpressed by the spells the Bon-chos attempted to cast on him. Instead, he awed them with his own tantric powers and bound the local deities by oath to become servants and protectors of the Buddhadharma. He established Tibet’s first monastery at Samye and founded the first of the four schools of Tibetan Buddhism, the Nyingmapa. Padmasambhava is often depicted in thangkas and wall paintings wearing the three robes of the monk and a red cap. It seems that en route to Tibet the guru landed in Ladakh. He left his mark in a few places.

Tak Thok Monastery above Sakti village, just off the Karu-Pangong Tso Road, grew around a cave where he is said to have meditated. Another site is on the Leh-Srinagar highway and revered by Buddhists and Sikhs alike. The Patthar Sahib Gurudwara enshrines a rock with a palm imprint believed to be of the first Sikh guru, Nanak, who had travelled to Ladakh in the 16th century. The Tibetans have long revered Nanak as an incarnation of Guru Padmasambhava.

Ladakh Takes Shape

In the 10th century, Tibetan king Nyima Gon, together with some central Tibetan noblemen, migrated westward towards Ladakh. In a sweeping gesture of generosity he gave his son Palgyi Gon the area extending from the present-day eastern border of Ladakh to the Zoji La pass near Sonamarg on the Leh-Srinagar highway — an area which belonged not to Nyima Gon but to small, independent principalities, whom Palgyi Gon subdued to establish his kingdom. Palgyi Gon’s territories later extended to Guge in the upper Sutlej Valley in western Tibet, and included Zanskar, Spiti and Kinnaur. At the time Ladakh looked not to Tibet for spiritual succour but towards Kashmir and north-west India.

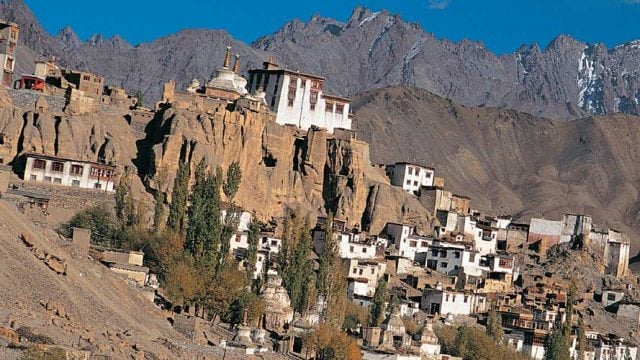

In the 11th century, King Yeshe Od, who moved the capital to Guge, sent Lotsawa ‘The Translator’ Rinchen Zangpo to Kashmir and other Buddhist centres to study and absorb Indian Buddhist traditions. Yeshe Od became responsible for the ‘second transmission’ of Buddhism into Tibet (the first being Padmasambhava) when he invited the great Indian master Dipankar Sri Gyan Atisha from the monastery of Vikramshila in Bihar to Tibet. Atisha introduced the famous lojong or ‘Mind Training’ which is the bed-rock of Tibetan Buddhism even today, set up the Tibetan monastic tradition and his disciple established the Kadampa tradition, which became the inspiration of the later schools of Tibetan Buddhism — the Karma Kagyu, Sakya and Gelug. Meanwhile, Lotsawa Rinchen Zangpo returned to his native land after accomplishing his task, bringing with him the finest artisans from Kashmir. He set about constructing 108 monasteries. Nyarma, close to Thiksey monastery, is definitely associated with him, although it is now in complete ruins. The others: Lamayuru, the earliest surviving monastery of Ladakh was enlarged and embellished by Rinchen Zangpo; Chiktan, Basgo, Mangyu and Alchi are said to be inspired by, if not directly connected with him.

The Translator at Alchi

The most celebrated of the monasteries associated with Rinchen Zangpo is one that fell into disuse probably around the 16th century, the Alchi Choskhor, an ancient centre of learning. The remarkably preserved murals at Alchi are very different in style from the Tibetan-influenced Buddhist art that prevails in the entire Himalayan region. Since Buddhist art was effaced from Kashmir and northern India, first by a resurgent Brahmanism and later by Islamists, Alchi is perhaps the best example of what must have once been the Kashmiri style of Buddhist iconography, which saw its cultural climax in Alchi. By the early 13th century, with Buddhism on the decline in India, Ladakh for the first time fully turned towards Tibet for spiritual guidance. From this period onwards Ladakhi monks went to Tibetan universities to study the dharma, thus beginning a process whereby Ladakh became part of the Tibetan cultural empire, rather than developing its own unique Buddhist culture. The first recorded Buddhist literature in Ladakh as well as the building of Likir Gompa belongs to this period.

Imprint of Naropa at Lamayuru

The site of Lamayuru, perched on a rocky promontory high above a village, is believed to have been chosen by the Bengali yogi Naropa in the early 11th century. Naropa, a great scholar at Nalanda University and also a siddha, wrote the famous treatise The Six Yogas of Naropa, and became the guru of the Tibetan yogi, Marpa, who in turn taught Tibet’s most celebrated yogi, Milarepa, who in turn taught Gampopa, the adept who established the Kagyu school of Tibetan Buddhism. When at Lamayuru, ask the monk on duty to show you Naropa’s cave, where the great adept meditated.

The early 14th and 15th centuries saw violent exchanges between Ladakh and Kashmir. The strangest of events took place when a Ladakhi adventurer called Rinchen went to Kashmir and became its first Muslim ruler. In 1420 the great Sultan Zain ul-Abidin, who brought a splendid cultural renaissance into Kashmir, must have needed to replenish his coffers. This he did with regular raids into Ladakh in search of booty and tribute, going as far west as Guge in western Tibet. The next 200 years saw Balti and Central Asian rulers following suit, which resulted in much conversion to Islam in the areas around Kargil. During this political turmoil, an emissary of the great Tibetan lama Je Tsongkhapa, founder of the Gelug School, arrived from central Tibet and was welcomed by the Ladakhi king, at whose instance Spituk monastery was founded, which today greets passengers arriving at Leh airport. Spituk is thought to be built over an earlier 11th century monastery whose remains may be seen at the summit of the hill. Near the foot of the hill, to the north-west, are rock engravings of Tsongkhapa and his disciples. Above the du-khang (prayer room) are chapels dedicated to Tsongkhapa, which also house a library of his writings.

The Namgyal Dynasty

In the early 16th century Ladakh was divided between two brothers who had their capitals centred at Leh and Shey and Basgo and Temisgam, respectively. Bhagan, the king of Basgo, made war on his cousins at Shey and after deposing them, united the kingdom of Ladakh and took on the title of Namgyal, ‘the victorious’, which became the name of the dynasty in power until the Dogra invasion under Zorawar Singh in 1834.

Bhagan’s younger son Tashi Namgyal (1555-75) was equally energetic, first gouging the eyes of his elder brother and ascending the throne, and then bringing Kargil in the east and Guge in the west under Ladakhi control. On the hill above Leh, Tashi built the Namgyal Tsemo, or Temple of the Guardian Deities, still in good repair. Tashi is said to have placed bodies of his enemies in the foundation of the temple. The earliest known portrait of a Ladakhi king, that of Tashi Namgyal, exists as part of a court scene besides the guardians that adorn the walls. The temple is part of a fort, the first royal residence at Leh. He also built the monastery at Phyang, 15 km west of Leh. At the roadhead, Tashi Namgyal erected a large prayer flagpole. Anyone who committed a crime against the king’s person or property and reached the pole before being caught would be granted clemency.

Tashi Namgyal’s nephew Tsewang Namgyal succeeded him and extended Ladakh’s boundaries eastwards to Mustang (now in north-west Nepal), south over Kullu (in Himachal Pradesh), and west over Baltistan, Gilgit and Chitral (in PoK). It seems he was all set to make war on the Central Asian kingdoms when traders from the Nubra Valley begged him to desist, as a war on the northern borders would seriously damage trade along the Silk Route. Tsewang left Leh and moved his capital back to Basgo, embellished the palace and built a Maitreya temple. Diego d’Almeida, a Portuguese merchant who spent two years in Tsewang’s capital and wrote the first European account of Ladakh, described the country as being wonderfully prosperous. Words, alas, that spelt doom, for soon after Ladakh was overrun and plundered by the Balti overlord, Ali Mir. Tsewang’s brother, the new king Jamyang was kidnapped and taken prisoner to Skardu (now in PoK).

Jamyang Namgyal’s initial misfortune led to a situation where he suddenly and fortuitously found himself related to the Mughal Emperor Jehangir. Popular tradition celebrates an affair of the heart between the hapless prisoner and Ali Mir’s daughter. Was there an unwanted pregnancy and a hurried marriage to salvage the Mir’s honour? A legend relates of the Mir having a dream in which he saw a lion jumping out of the river and entering his daughter’s belly. At that very moment, says the legend, Gyal Khatun conceived. Ali Mir, obviously a powerful chieftain, had given one of his daughters in marriage to Jehangir, which made Jamyang a brother-in-law to the most powerful man in Asia. Obviously, Jamyang couldn’t remain prisoner and Ali Mir let him return to his kingdom with the consolation that in all probability his heirs would be Muslims. No such inroads existed for the Baltis as the Ladakhis turned their queen Gyal Khatun into an incarnation of the goddess, White Tara, and remained good Buddhists. The child born out of the union was called Sengye (Lion) Namgyal and became the greatest builder of the dynasty.

Sengye’s bequest

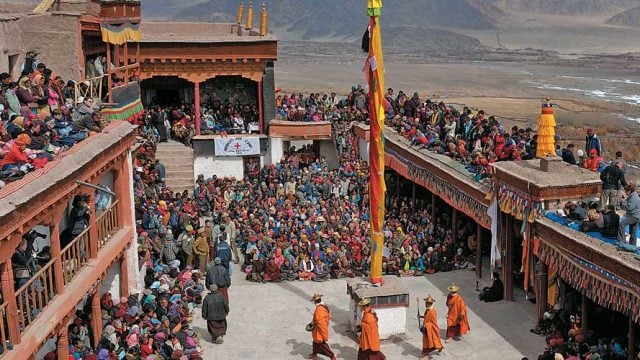

The first of his creations was the massive monastery of Hanle, east of Tso Moriri Lake. The second was the equally massive Hemis Gompa, nestled in a cleft of the Zanskar Range. Sengye shifted the capital from Basgo back to Leh, indicating the growing importance of the latter as a trading post on the busy trans-Karakoram trade route. He installed the giant Buddha statue at Shey and below the Namgyal Tsemo, raised the nine-storey Leh Palace, a small imitation of the great Potala in Lhasa. In between, the lion found time to expand his empire by annexing Zanskar and Guge. Buoyed by this success, he turned westwards, taking on the combined Balti-Mughal army at Bodh Kharbu, west of Lamayuru on the Leh- Srinagar road. He suffered a miserable defeat in 1639 and had to sue for peace, promising the Mughal Emperor an annual tribute, which he later refused to pay. Piqued by his rout, Sengye clamped the vital artery of the Kashmir-Leh trade route and forbade any traveller from Kashmir to enter his dominion. It was a case of cutting the nose to spite the face as he lost a fortune in the huge revenues from trade that would have accrued.

Visitor from the west

Sengye’s second creation Hemis Gompa is the largest and wealthiest of Ladakh’s monasteries. A curious tale involving a Russian Jew and Jesus Christ brings many visitors who are in the know to Hemis. In 1887 a Russian aristocrat and gentleman adventurer by the name of Notovitch arrived in India and proceeded to Ladakh. There he apparently fell off his horse while riding near Hemis and was carried up and taken care of by the kindly monks. One of these monks, according to the Russian, showed him some manuscripts that he had translated. To his shock he found an ancient account of the life of Jesus Christ from the age of 12 to 30, where the messiah is supposed to have travelled to India and received teachings at Buddhist universities before returning to Palestine to preach the Gospel. On his return and the publication of his book, Notovitch was denounced as an apostate and fraud.

But the controversy of the Hemis Manuscripts refused to die down. In 1922, determined to expose the Russian, a monk from the Ramakrishna Mission in Calcutta, Swami Abhedananda, travelled to Hemis. On his return he published his findings in Kashmir O Ladakh, his Bengali travelogue, which corroborated Notovitch’s translations. Not to be outdone, Nicholas Roerich journeyed to the monastery three years later and claimed to have seen the very manuscripts. Soon after, it is said, the monks at Hemis secreted the controversial documents that were evoking such furore, and to the present day deny their existence.

The Fall of the Namgyals

Shey Palace, standing on a spur which runs out almost to the edge of the Indus, is the ancient capital of the Ladakhi kings. Even after Sengye Namgyal had built the Leh Palace, the Ladakhi rulers continued to think of Shey as their home until the Dogra invasion. There are extensive remains of a fortress on the hill at Shey, said to be of the earliest rulers of Ladakh, even before the Tibetan invasions of the 9-10th centuries. The palace, built later, resembles the one at Leh. In an older, more modest structure some 300 m away, stands a gigantic Shakyamuni sculpture, said to have been built at the instance of Sengye Namgyal by Nepalese craftsmen sent for by his mother, Gyal Khatun.

Sengye had three sons, between whom he carved his empire. To the eldest, Deldan, he gave Ladakh, the middle son inherited Guge and the youngest, Zanskar and Spiti. Incorporated into Shey Palace is a temple with a copper and gold Shakyamuni Buddha, said to have been installed in Deldan’s time.

Deldan Namgyal’s problems began almost immediately on accession when Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb visited Kashmir and the small matter of the nonpayment of tribute by the Ladakhis was brought to his notice. A chastened Deldan bent his knee before the emperor’s will, promising tribute and loyalty, the lifting of the trade embargo with Kashmir, and the first mosque in Leh, which was built in 1666-67. Deldan had problems in the east as well. Ladakh backing Bhutan in the Tibet-Bhutan war irritated the Tibetans, already uncomfortable with Leh’s acceptance of Mughal suzerainty. In 1679, a small Tibetan army arrived at Ladakh’s eastern borders, where it clashed with Deldan’s army and drove it far west to Basgo. There, the king was held under siege for three years until the Mughals responded to calls for help and chased the Tibetans away.

Final Ladakh-Tibet border

This time, the Mughals formalised the earlier lax agreement and extracted the tribute of 18 piebald horses, 18 pods of musk, 18 white yaks’ tails every three years, plus a monopoly of the purchase of pashm. This wasn’t such a bad deal as the Ladakhis also received 500 bags of rice. The only catch was that Deldan was now obliged to convert to Islam and was known as Aqibat Mahmud Khan, a fact usually stoutly denied by the Ladakhis. News of the conversion worried Lhasa, who sent an emissary to Leh to negotiate a settlement. Deldan was in no position to bargain and gave away the western territories of Guge, and by the Treaty of Tingmosgang (present-day Temisgam) in 1684, the boundary between Ladakh and Tibet was fixed, where it lies today, bisecting Pangong Lake.

Here began the decline of Ladakh as an independent kingdom. Occupying an ambivalent position between powerful neighbours Tibet and Kashmir, Ladakh literally fell between two stools. When the Chinese extended suzerainty over Tibet in 1720, Ladakh bent its knee at the court at Peking. By the 18th century the House of Namgyal was divided by disputes and family intrigue, and within a hundred years, the last independent ruler, the indolent and ineffective Tsephal Namgyal, surrendered his kingdom to the Dogras. In return, the Namgyals were stripped of their title as Gyalpos of Ladakh and ousted from Shey. They were given the jagirdari of Stok, where they still live today.

Ladakh’s Geography: A ‘different’ land

For a tourist, the defining experience of this northernmost tract of India is in its landscape: largely pristine, beautiful, disconcertingly bare, isolated. Ladakh changes geography from a boring school subject into a superb drama of altitude and terrain. A drama in which you can thrill to any random reference point: The Great Himalaya, the Zanskar Range, Indus River, Siachen Glacier…. Ladakh lies beyond mountains so high that monsoon clouds can’t cross over to nourish the land, creating a high altitude desert. Only two proper highways that link Leh to Srinagar and Manali breach these mountains. But Ladakh experiences harsh cold weather for so long that the mountain passes are snowed under between late October and June, cutting off road travel into Ladakh in winter, leaving it remote and inaccessible till year-round flights started to Leh.

Ladakh lies at the topmost stretch of India, sharing its eastern borders with Tibet, such that Pangong Tso lake falls partly in Tibet and partly in India. The western regions of Ladakh are those made infamous by proximity to the Line of Control — including the towns of Kargil, Drass and Batalik. North is the heavily contested Siachen region and Pakistan-occupied-Kashmir.

The southern edge of Ladakh is formed roughly by the Great Himalayan Range, which runs south-east to northwest, and nearly all the other primary features of Ladakh’s geography follow the same direction, in repetitive, parallel lines. The next range is the Zanskar Range. The Stok Kangri peak, a part of the Zanskar Range, is visible from all over Leh, painting the town’s background with grandeur and snow. Between the Great Himalaya and the Zanskar fall the Suru and Zanskar rivers, and their valleys. The Zanskar region is still a relatively less-known part of Ladakh, most familiar to trekkers.

Roughly parallel to the Zanskar Range, again on a southeast-northwest axis, lies the heart of Ladakh, the area most familiar to non-Ladakhis: Leh and the now-famous Buddhist monastery-villages along the Indus River, in Central Ladakh. The Indus emerges in western Tibet, from near the northern face of Mount Kailash, enters Ladakh at its southeastern border at Demchok, and flows north through the region’s middle, creating a cultural backbone for it. It also accepts the tribute of practically all rivers you’ll hear of here: Suru, Zanskar, Shayok, Nubra. The Indus, and the meltwater streams that flow into it were the only means of irrigation for Ladakhis who settled here. They created the oases of green fields, poplars and willows, bright springtime and gold-and-orange palettes of autumn, Buddhist traditions and monastery treasures, all bursting out of a brown canvas. From south to north, it is a litany of names: Leh, Hemis, Stakna, Thiksey, Stok, Shey, Leh, Spituk, Phyang, Basgo, Likir, Alchi, Ridzong, Lamayuru.

To the north of Central Ladakh rises the Ladakh Range. If you want to go to the Nubra region you have to cross Khardung La in this range. The Nubra region consists of the valleys of the Nubra and Shayok rivers, which meet here. This valley is known for its abundance of the seabuckthorn berry, for the double-humped Bactrian camels and sand dunes along the old Central Asian caravan route. The Ladakh Range branches off into the Pangong Range in south-east Ladakh, which you can see from the southern shore of Pangong Lake. Further south-east lies a continuation of Tibet’s Changthang Plateau. This area is such an agglomerate of disorganised peaks, plateaus and ridges that meltwater here finds no proper slope to flow away, forming the beautiful saltwater lakes, Pangong Tso, Tso Moriri and Tso Kar.

It is these ancient rivers and oases, these shifting cold desert sands, these mountain vistas — these grand flourishes of geography that continue to draw travellers from all corners of the Earth to the high altitude desert of Ladakh.

Circuits of Discovery

Welcome to the highest, furthest and largest corner of India! There’s an awful lot to do in Trans-Himalayan Ladakh. These key circuits will help you make the most of it.

Central Ladakh Leh, the magnificent oasis beside the Indus lying between the Zanskar and Ladakh ranges, is the base for visits to Hemis National Park, the climb up Stok Kangri Peak, and to the old palaces and gompas strung along the river. Ladakh’s most imposing edifices are these gompas. Capital city Leh is also home to three gompas, the old royal palaces and numerous family-run guest houses, travel operators and cafés.

Nubra Valley Lying between the Ladakh and Karakoram ranges, roughly to the northeast of Leh across the Khardung La, this valley’s borders touch PoK and Tibet, China. It offers the quiet settlements of Tegar and Panamik on the Nubra river, Diskit and Hundar on the Shayok river, and the recently opened village of Turtuk, which is barely 12 km from the Line of Control. And not least, the double-humped Bactrian camels that roam the white sand dunes near Hundar, reminders of the ancient caravan-laden Silk Route.

Zanskar To the west and south of Leh, this valley is relatively less explored because it is connected by road to Leh by a circuitous route via Kargil, and that too only for a few months. That’s also why some of the best trek routes in Ladakh run through Zanskar. The Zanskar River is remote and beautiful, and the only one in Ladakh high enough to raft in summer. The 120- km-long run from Padum in Zanskar to the confluence of the Indus and Zanskar at Nimmu near Leh, passes through magnificent mountain gorges and offers some thrilling whitewater. This same stretch freezes over in winter, when you can do the famous Zanskar ‘Chadar’ trek.

Dah, Hanu and Kargil The string of Drogpa villages lying between Khaltse and Batalik along the Indus River west of Leh can be combined with visits to Kargil and Drass, the second coldest place on Earth. Kargil can also be visited en route Zanskar.

Great Lakes The sublime high-altitude lakes — Pangong Tso, Tso Moriri and Tso Kar — lie to the south-east of Leh within the Changthang Cold Desert Wildlife Sanctuary, where the bharal or blue sheep, the great Tibetan sheep, Tibetan antelope, serow, ibex, snow leopard, red fox and kiang, the Tibetan wild ass, roam. The lakes are home to Siberian and Tibetan species of birdlife.

PERMITS

Both Indian and foreign travellers need Inner Line Permits to visit many places outside Leh, such as the Nubra Valley and Pangong Tso. You can get them yourself from the authorities below, but it’s easiest to arrange permits through a travel operator or your hotel. You will need a copy of valid ID proof. The permit is valid for one week. Foreign tourists must carry their passport and go in groups with registered guides

Deputy Commissioner, Leh Polo Grounds, Tel: 01982-252010/ 27 , Timings: 10 am-4 pm

Ladakh Autonomous Hill Development Council (LAHDC), Leh District Tel: 252010/ 27; Website: leh.nic.in

LAHDC, Kargil District , Tel: 01985-232216, 232222, Website: kargil.nic.in

Ladakh is not for the acrophobic. Ladakh literally means ‘land of the high passes’, or La- Tags. Here you will find Khardung La, at 18,380 ft the world’s highest motorable pass, which leads over the Ladakh Range to the Shayok and Nubra valleys. The second highest motorable pass, Taglang La (17,480 ft) on the Zanskar Range is crossed on the 473-km drive from Manali to Leh. Chang La (17,290 ft), also on the Ladakh Range on the approach to Pangong Tso, is the third highest motorable pass

The capital Leh itself stands at 11,500 ft, thus housing the highest airport in India. Leh’s Polo Ground, at 11,480 ft, is said to be the highest in the world. The world’s highest observatory, at 14,820 ft, is in the village of Hanle, deep inside Changthang Sanctuary. Ladakh also has the dubious distinction of being the home of the world’s highest battlefield, that of Siachen at a whopping 20,669 ft, which is serviced by the world’s highest helipad, just below 21,000 ft.

The high altitude means that if you arrive in Leh by air from the plains, you must spend some time acclimatising to the lower oxygen levels at these heights before attempting anything strenuous. You could experience breathlessness, lethargy, headaches, nausea and insomnia. Take it easy for the first 24 hours, and drink plenty of water. Expect to go to the bathroom a lot. Avoid alcohol. For Acute Mountain Sickness Emergencies, call Leh’s Sonam Narboo Hospital (Tel: 01982-253629).

Ladakhi Ways

Abutting the eastern edge of the Tibetan plateau, which ends just north of Leh at North Pulu above Khardung La, Ladakh often gives visitors the exotic feel of being in a mini Tibet. Ladakhi people share their ethnicity, the mystical Vajrayana form of Buddhism, crops like barley and food such as barley-based tsampa flour and the slightly alcoholic chhang, and much more, with Tibet.

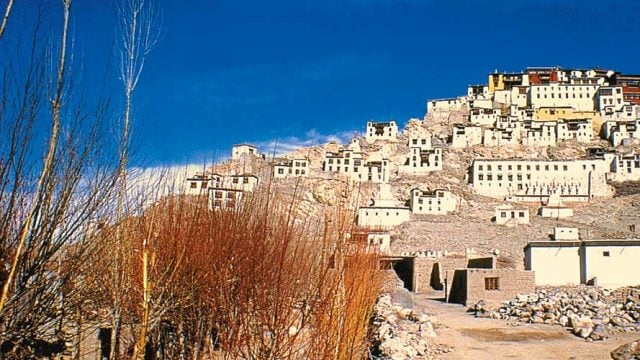

In extreme mountain desert climatic conditions such as Ladakh’s, cultural heritage has often simply meant the way people adapt to the altitude, seasonal patterns and ecology. Leh, as well as the monastery-villages along the Indus, are oases in the central part of this mountain-desert. Go to any village and you will be enchanted by this oasis quality: the drawing together since forever of human beings where there is water and possibility of life, the sound of water bubbling down irrigation channels, the intense green of the standing crop, the silence, and the potential for your very being becoming quiet. You will see fields of barley, white houses with painted doors and windows, colourful prayer flags, and at the very top of the mountain, a Buddhist monastery guarding the whole.

Ladakhi homes, Basgo Village

Scarcity of rain and arable land has meant that village houses often cling to hillsides above the fields so as to not waste fertile soil. Ladakh’s small, white-washed houses with flat roofs belong to a place that sees no rain, and hence do not need sloping roofs. These flat roofs can also store ample animal fodder for the unproductive winter months. Long winters also mean extended wedding celebrations that go on for days, and feasts and festivals galore. Just as they mean vast warm kitchens with ample seating, in which to sip chhang or gur gur cha for hours. The cha, Ladakh’s ubiquitous butter tea, is a fat-laden beverage essential for the body in these excessively dry climes.

Also, spot how Ladakhi fields are irrigated by water channels cut into the mountain slopes used cooperatively by farmers, channels which carry melting snow waters across long distances to these fields. Each farmer blocks the channel with stones, waters her fields till sufficient, and then scrupulously removes the stones so that the water moves on to other fields downstream.

In a context of scarcity of resources, says scholar Helena Norberg-Hodge, “What cannot be eaten can be fed to animals, what cannot be used as fuel can fertilise the land…. Ladakhis patch their homespun robes until they can be patched no more. Finally, a worn-out robe is packed with mud into a weak part of an irrigation channel to help prevent leakage…. Virtually all shrubs or bushes serve some purpose” (as fuel, fodder, roof material, fence material, dyes, basket weaving and so on). Even human faeces was not wasted. Each house had a dry composting latrine with a hole far below. Earth and kitchen-ash was added to the waste “to help decomposition, produce better fertiliser and eliminate smells”. This dry compost was used in the fields.

The best way to experience the Ladakhi way of life is by staying with the Snow Leopard Conservancy’s Himalayan Homestays (Web: himalayan-homestays.com) programme. Opt for their Lugnak Trek based out of their homestays in remote Zanskar.

Scenematic: Ladakh in the Movies

Ladakh is a hugely popular location for movies, ad films and music videos, giving stiff competition to the old cinematic heart throb, the Vale of Kashmir. It all began with the gritty realism (by Bollywood standards) of Chetan Anand’s war movie Haqeeqat (1964). Since then, many film crews have shot among Ladakh’s awe-inspiring moonscapes.

The vast blue waters of Pangong Tso and the commanding ruins of Basgo are particularly favoured locations. In Bunty Aur Babli (2005), Abhishek Bachchan and Rani Mukherjee romance in the midst of the Basgo ruins beside the Indus, and through the chorten-filled fields that lie between Shey and Thiksey gompas. Basgo is also the startled backdrop of Akshay Kumar and Kareena Kapoor crooning “White white face dekhe, dil woh beating fast sasura jaan se maare re” in the hit song Dil Dance Maare from Tashan (2008). Ten years before them, Pangong Tso and Basgo were the backdrop for Shah Rukh Khan and Manisha Koirala’s ‘Tu Hi Tu Satrangi Re’ from Dil Se (1998). Shah Rukh Khan was back beside Pangong Tso for Jab Tak Hain Jaan (2012), in which Thiksey Gompa also stars. More views of beautiful Pangong can be spotted in the ‘Subah Hogi, Shaam Hogi’ song of Waqt: The Race Against Time (2005), in which you can also more the merging waters of the Indus and Zanskar at Nimmu, just west of Leh.

At Pangong Tso in Dil Se

Danny Denzongpa’s award-winning Frozen (2007), on the life of an apricot jammaker’s family in a remote Himalayan village, is shot entirely in Ladakh. In Raj Kumar Hirani’s 3 Idiots (2009), spot the bridge over the Indus River, the Druk White Lotus School at Shey, and Pangong Tso. Farhan Akhtar spent five months shooting war drama Lakshya (2004) in Ladakh, and was back there to train for his role as ‘The Flying Sikh’ Milkha Singh in Rakeysh Omprakash Mehra’s Bhaag Milkha Bhaag (2013). And of course, JP Dutta could have chosen no better location for his LOC: Kargil (2003) than Ladakh.

art

Buddhism

Changthang Plateau