In today’s tranquil Anandpur Sahib, it’s hard to visualise the violent events of the 17th and early

Guru Gobind Singh continued to face persecution by the Mughals, who were in cahoots with the Raja of Bilaspur, in whose territory Anandpur was located. The assault on the Sikhs continued. Finding Anandpur an easy spot to defend, Guru Gobind Singh built a stronghold of five interconnected fortresses in 1688 that dominated the landscape and withstood sieges against overwhelming odds. The remains of those fortresses are now consecrated gurudwaras.

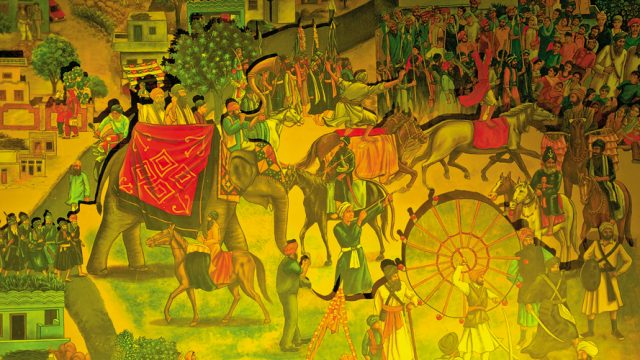

Finally, in 1705, Guru Gobind Singh was tricked — by an offer of safe conduct from an alliance of hill Rajputs and Mughal faujdars— into leaving Anandpur Sahib after a siege of some seven months. A running battle ensued, that has entered folklore. At a flooded ford now known as Parwar Vichhora Sahib, the guru was accidentally separated from his two youngest sons and his elderly mother. The children were betrayed and tortured to death and their grandmother died from the shock. The guru’s two elder sons also died in the battle at Chamkour Sahib, fighting 20 to one. It was perhaps these multiple tragedies that led him to preempt any possibility of a struggle for succession by declaring that the Sikhs would henceforth follow the Guru Granth Sahib rather than another living guru. The history of the Punjab plays out elsewhere after that siege of Anandpur, and subsequent events revert to locales further west. But Anandpur is where the Khalsa was forged.

blog

Guru Gobind Singh

history