Leisure travel abroad for salaried Indians is generally subsidised by work. I was off to attend a

At 8.30 one morning, Amitav and I formally inspected the rental car that had drawn up by his guest house, were told that the car didn’t have a built-in navigation system which Amitav had asked for, and were given some rudimentary road maps instead. The owner of the guesthouse, a hyper-animated Afrikaner called Dawie, explained in some detail how to get to the highway.

The driving time to Kruger from Johannesburg was six hours. Amitav would drive all the way (he had an American driving licence which was valid in South Africa whereas I needed an International Driving Licence which I didn’t have) and I’d do the map reading. We got lost immediately. My map-reading skills, Amitav’s intuition and Dawie’s instructions, kept us in Johannesburg for quite a long time. Mainly Dawie’s instructions: he had promised us that we’d see three robots before the crucial left turn. Not wishing to seem third-worldish I looked for the robots and didn’t see one. Later in the drive when I phoned Dawie for further instructions, he explained that robots was Afrikaans for traffic lights (because they changed colours automatically) and then laughed a lot in a guttural way.

I phoned Dawie because we had been on the right highway for half an hour, only travelling in the wrong direction because South African signage was at once unfamiliar and curiously elaborate. Dawie gave us detailed directions to a bypass that would take us to the motorway that led directly to the Manelane Gate (the southern entrance to Kruger) but which took us straight to the arrivals area of a suburban airport. Swearing, Amitav found his own route to the relevant motorway and when we were roughly ninety kilometres short of Manelane Gate, I called the lodge where we had booked our rooms to ask for detailed directions once we entered Kruger.

Luckily Amitav’s intermediary in this transaction came to our rescue. After she finished with the erring travel agent who she had commissioned to make the reservation, we got a call from a young woman who was very keen to set things right. We were, she explained, now booked into a very deluxe lodge, very close to the one we had originally been destined for, very much more expensive than the previous one, but the travel agency would pay the difference. Reassured, we left the parking lot and reached Manelane Gate half an hour before it closed at dusk.

Inside five minutes of entering the park, we saw our first substantial animal (I’m not counting deer which are to wildlife sanctuaries what weeds are to gardens) — a rhino. After a quarter of a century of bourgeois travelling, I’ve arrived at a convergence theory of national parks, which is that all national parks are the same national park. Whether you’re at B.R. Hills near Mysore or in Sariska near Alwar or Kruger, there’s a road in the middle and scrubby wilderness on either side. The difference in Kruger was that there was visible wildlife as well, as evidenced by the rhino. It must have been all of twenty feet from the car and it was being stared at by a Land Rover full of safari-ing tourists. Amitav wanted his camera, so I opened the door and half-stepped out to fetch it from the back of the car when something — it could have been the alarmed faces of the Land Rover lot or Amitav hissing “get back in, you idiot”, or the beady stare of the two-horned beast-stopped me. It was embarrassing but nothing happened and we had bagged our first big one.

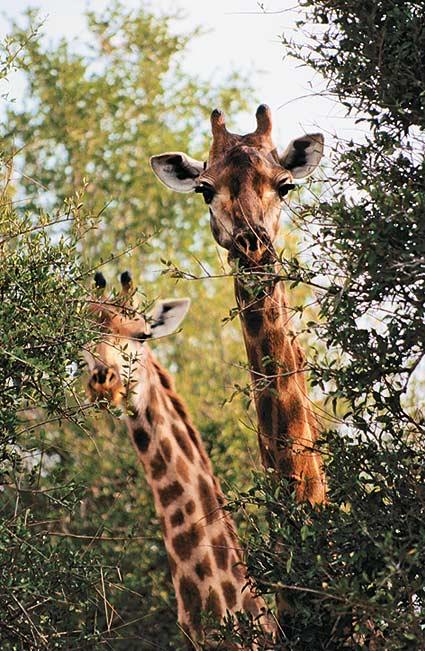

By the time we got to our lodge we had seen several giraffes. Giraffes aren’t native to Kruger. They are intelligent extraterrestrial life forms masquerading as earthly animals. I saw it at once in their lofty indifference to everything around them. We also saw two elephants, a big one and a little one which could have been its child but we couldn’t tell what sex they were partly because it was dusk but mainly because we didn’t know exactly where to look on an elephant. Specially the African elephant, which is enormous. Ours seemed puny in comparison. I felt a pulse of elephant patriotism. This lot were large good-for-nothings. They couldn’t be taught or tamed or trained to do anything. They just hung around in profile, staying still so people could take pictures. They made great silhouettes, though. They were so big that driving past one was a bit like driving by India Gate.

When we reached our lodge, Little Jock, I thought we had died and gone to heaven. It had Land Rovers in the front court and it was built in a thatched, rugged-luxurious way that I knew at once I couldn’t afford. The cancelled booking and this paid-for upgrade was looking better by the second. A young woman met us at the door and while attendants removed our meagre bags, she gave us a welcoming glass of cold white wine. When Amitav asked to buy a bottle of wine, she produced a wine list and let slip that all the drink was on the house. I nearly asked if she meant I could drink all I wanted for free, but stopped myself. But yes, that’s exactly what she meant.

The lodge was built in the curve of a dry riverbed and the rooms were actually suites with wooden decks that looked out into the wadi. I heard leopards cough and deer rustle though I didn’t see anything and no elephant herd came visiting as they were rumoured to do. The two days we spent in Kruger were equally divided between eating and drinking and going on safari. Twice a day, at five in the evening and six in the morning, we set off with Lazarus, our ranger, in his massive Land Rover. Most of our safari time was spent driving in Little Jock’s 7,000-acre concession, where only guests of the lodge were allowed to travel. Each ride lasted three hours, so that was six hours spent jolting and gawping and it’s fair to say that we spent six hours eating and drinking.

Our morning safari was sensibly prefaced by coffee and fruit. Lazarus looked as if he was in his twenties, though he had a quirky, ironic way about him that suggested someone older. He was from the area — his parents were part of a local tribe. He spoke easy, fluent English and he drove the Land Rover with an effortless nonchalance through dipping, slipping, roadless terrain. I remember him stopping the vehicle so we could watch two white rhinos. One of them was defecating and he produced what can only be described as perfect, cylindrical shells that were expelled with such force that the crap was a kind of cannonade. After the rhinos left (both male, young: Lazarus could always tell the girls and boys apart, even in the dark) he drove us down to their lavatory which he called a midden.

I have a very bad video of him standing outside the Land Rover surrounded by rhino turds, explaining that a midden wasn’t just a place to shit for the rhino, it was also a place for acquiring information, his equivalent of a cyber-café. The midden told the rhino if there were any willing rhino maidens about, it told him if there were any pushy male rhinos horning in on his territory. Lazarus stopped to pick up an old rhino turd and crumbled it. You could tell from the turds, he said, if they had been produced by a black or a white rhino. The colour was different as was the content because the one grazed (ate grass) while the other browsed (ate twigs). It was fascinating but some part of me kept wanting him to wash his hands afterwards.

Lazarus taught us that the most dangerous animal for the tourist was the wild buffalo. We had just come across a group of them, great ugly creatures with enormous horns welded on their foreheads. Lazarus, normally the easiest and most relaxed of men, was unusually careful about keeping the Land Rover well short of this bunch. This wasn’t a normal herd of buffalo. It was a bunch of middle-aged males who had been expelled from the herd by the alpha male. As a result, none of them were likely to get much sex again, so they wandered and brooded and their testosterone levels rose till their frustration became so intense that they became capable of attacking anything — just completely unpredictable.

The Big Five in Kruger are the elephant, the rhino, the buffalo, the leopard and the lion. Big has nothing to do with size, otherwise the giraffe would figure. The big five are simply the animals that hunters wanted as trophies in the days when hunting was allowed. We saw the elephant, the rhino and the buffalo without any difficulty, but Lazarus was quite clear from the first safari on that there was no guarantee that we would see the other two. The big cats were elusive.

We never saw the leopard, though we saw his pugmarks and his dinner. On two occasions Lazarus showed us trees hung with antelopes. Well, one antelope each. The leopard would kill the antelope and to save his kill from hyenas he would hang the corpse astride a branch, looking languid and graceful as deer-like creatures do except for the fact that its neck hung at an odd angle or that its head was bitten off.

By the end of our second safari, the one in the evening, we had seen no sign of a lion and we were beginning to feel anxious at the thought that we would have to return to Johannesburg having scoured the length and breadth of Kruger without being able to report a single sighting. The thought of the rest of the literary festival crowd who had gone to Mabula, a little game park run by Vijay Mallya regaling us with tales of dozens of lions to our none was insupportable. As night fell, Lazarus stopped the Land Rover in the middle of a clearing bordered by brush and gave us leave to pee. “Don’t belly up to a bush,” he warned. “Do it in the open so you can see what’s in front of you.” So we obediently stepped away from the vehicle and angling ourselves away from each other began to widdle into the breeze which felt both strange and oddly intrepid.

By the time we turned around Lazarus had set up a table complete with tablecloth, flasks, ice-box and steel glasses. There, in the darkening clearing, surrounded by endless scrubby bush, under a luridly coloured sky, we drank our sundowners. Gin and tonics in a South African wadi: it was both absurd and wonderful. We drove back to the lodge with Lazarus driving one handed, manipulating a search light with the other, all the while keeping up a running commentary on the animals that sat transfixed by its beam.

The next morning’s safari, our last before we returned to Johannesburg, was more of the same. By this time, Amitav and I were shamelessly focused on spotting a lion but after two and a half hours we grumpily gave up. We were outside Little Jock’s concession, on public land making our way back to Little Jock when Lazarus exclaimed, “Look, lion!” We looked, but there was nothing to see and I’d be lying if I claimed that the cynical thought that Lazarus was making things up didn’t cross my mind. “I shouldn’t be doing this,” he murmured to himself, and then suddenly swung the car off the track (which he wasn’t meant to do because we were in the public part of the park where vehicles were meant to keep to the road) and drove into the brush.

The penny dropped: this was for real. Amitav and I reached for our cameras and we had barely fired them up when Lazarus twisted the Land Rover round a hedge-like thing and there less than 10 feet from us were two affronted looking male lions who heaved themselves up and padded away, wondering what the bush was coming to.

We were out of there in a flash, back on the road, legit again. “That’s more than my job is worth,” said Lazarus smiling. Amitav and I sagged back in our seats, clutching cameras filled with precious blurry pictures of retreating lions. We left Little Jock and Kruger, content.

In Johannesburg, when talk turned to wildlife and one of the literary party that had gone to Mabula spoke of the half a dozen lions he had seen, I smiled encouragingly and said nothing. We who have been to the Kruger, do not count.

The information

Getting there

First fly to Johannesburg. South African Airways and Jet Airways offer non-stop flights ex-Mumbai, from Rs 39,000 and Rs 33,450 return, respectively. Among other options is Emirates, which has connections from 10 Indian cities via Dubai (from approx. Rs 30,000). From Johannesburg, there are domestic flights to all three of the airports located around Kruger National Park (from Rs 6,000 one way on Airlink, flyairlink.com). You could also rent a car at the airport and drive to the Park (this could well be cheaper than flying; 5-6hrs).

Where to stay

For those on a budget, the Main Kruger Park Rest Camps ($20-700) offers a choice of tents and rooms. You can book these on krugerpark.co.za. High-end accommodation is also abundant. The Little Jock Lodge, part of the Jock Safari Lodge (from approx. $680, inclusive of meals and beverages, two safaris a day and walking tours; +27-735-5200,jocksafarilodge.com) and the Lukimbi Safari Lodge (from $350; 431-1120, lukimbi.com) are both recommended. For more accommodation options, visit the official Kruger site,sanparks.org/parks/kruger/.

Kruger National Park

safari

South Africa