The Irish spell whiskey with an E, while the Scots spell it without an E,” explains Andrew

We start off in Northern Ireland’s Antrim County, which has one of the most breathtakingly rugged coastlines in the world. Craggy green cliffs rise sharply out of the North Channel’s choppy waters, gulls swoop dangerously close to the breakers below, while a grey sky threatens rain. It looks cold, so I bundle up and step out to experience the wonders of the Giant’s Causeway, a World Heritage Site. A series of volcanic eruptions 60,000 years ago saw molten lava cool rapidly into polygonal-shaped columns that look eerily manmade. About 37,000 basalt columns extend from the cliffs into the sea in fanciful formations reminiscent of a camel, a wishing chair, a harp and an organ. So much for the geological explanation; the Irish, of course, have their own. The biggest and bravest of the Irish giants, Finn McCool lived here with his wife, Oonagh. He built the causeway to fight his archenemy, Benadonner, who used to shout insults at Finn from across the sea in Scotland.

As I begin to clamber up the giant-sized columns, the skies open and the rain lashes down in buckets. Soaked to the bone, I slip and slide towards the ‘wishing chair’, precariously situated near the crashing waves. I meet two women, hair plastered to scalps, who are similarly struggling across Finn’s now-perilous hexagons. “Some breeze, eh?” I say, attempting cheery conversation. “Breeze?” responds one, “Breeze? It’s a blooming hurricane!” We make our bedraggled way back to the coach. I’ve now acquired a first-hand understanding of Irish weather, summed up in the adage, “If you can see the hills, it’s going to rain; and if you can’t, it’s raining.”

We pass undulating glens, their slopes dotted prettily with picnic tables. I keep a sharp lookout for little people — Antrim’s glens brim with leprechauns, elves and fairy folk of all persuasions. “Supernatural experiences are called ‘happenings’,” says Andrew, as he embarks on an anthropological exposé of the Irish wee folk. The most famous, of course, are the leprechauns. Standing two feet tall, these little old men are guardians of ancient treasures who are often found intoxicated after imbibing vast quantities of home-brewed poteen. Irish fairies are even more colourful. Pookahs are nasty shape shifters who create mischief in the guise of goblins or bogeymen, the mere sight of whom prevents hens from laying eggs. Grogochs are hairy fairies not noted for their personal hygiene, who often lend a hand tilling the fields in return for fresh cream. On we go, past the Bushmills Distillery, Ireland’s oldest licensed whiskey distillation unit. “You can smell the whiskey if the wind is right,” says Andrew, swelling with pride. We reach the historic Bushmills Inn that has magically recreated its origins as a 1608 coaching inn, replete with ivy-covered walls, fireplaces and secret doors hidden in bookshelves. I settle down to a lunch of chicken breast on a spinach-lentil-goat cheese salad, rounded off with a hot toddy made from whiskey, cloves and demerara sugar.

Back on the coast, we pass the thirteenth-century ruins of Dunluce Castle clinging magnificently to a cliff overlooking the North Atlantic. It was once the headquarters of Antrim’s MacDonnell clan. “One evening,” says Andrew, “the butler announced that dinner would be late. ‘Why?’ asked MacDonnell. ‘Because the kitchen has fallen into the sea’.” Strangely, the story is true; Dunluce was abandoned soon after.

Leaving the blustery coast, we head south past wild moors, rich in peat and purple heather. We stop at Dungiven to visit Flax Mills Traditional Crafts, where Marion and Hermann Baur demonstrate intricate weaves on a lovingly restored fly-and-shuttle mill. It becomes abundantly clear why Irish linen is still considered the finest. At day’s end, we check into the Ardtara Country House, a nineteenth-century mansion set in eight wooded acres. Once the residence of the Clark family, world-famous linen makers, each of its rooms is styled with king-size beds and original working fireplaces. The sumptuous interiors spill over into a heavenly meal (hay-smoked salmon, fillet of comber beef, pavlova) and talk turns to the more malevolent of Irish sprites such as banshees and ghosts — the white lady of Dunluce who died of a broken heart; Lady Isabella of Ballygally Castle who jumped to her death and so on. In the flickering firelight, even the benign leprechauns begin to take on a dastardly hue. By the time Andrew recalls the rhyme, “Up the airy mountain; down the rushy glen; we daren’t go a-hunting; for fear of little men”, my desire to experience a ‘happening’ has rapidly declined. Sensing our thinly veiled terror, the maître d’ announces firmly, “We have no ghosts.” We laugh nervously and shuffle off to bed in a hurry.

In Belfast, I take in the city’s sights. There’s the iconic City Hall with its soaring 53-metre copper dome and the Beacon of Hope sculpture, a female figure holding aloft a ring of thanksgiving, better known to local wags as the Doll on the Ball or the Thing with the Ring. Then, the red-brick Queen’s College, founded by Queen Victoria, whose notable alumni include Nobel Laureate and poet Seamus Heaney. Belfasters are a little churlish about the fact that several of the city’s sights are named after the Hanover queen. There’s Queen’s College, of course, but there’s also Victoria Square, Victoria Street, Victoria Park… “She was only here three hours; thank goodness she wasn’t here a week,” they say.

But most intriguing is the Peace Wall, which separated Protestant unionists and Catholic nationalists during the period of civil unrest known as the ‘Troubles’. Drive down Shankill Road on the Protestant side or Falls Road on the Catholic side to view the political murals lining the wall, from Che Guevara (who apparently had Irish ancestry) to the Red Hand of Ulster, official emblem of the illustrious O’Neils. We halt for the day’s highlight — the Titanic Walking Tour around Queen’s Island — where shipbuilders Harland & Wolff built the three White Star Liners, the Britannic, Olympic and, most famously, the Titanic. Our guide Ed, a confirmed Titanorak, starts us off in the main offices. We stand in the room where chief draughtsman, Alexander Carlisle, and managing director, Bruce Ismay, had their fateful argument regarding how many lifeboats the Titanic should have. According to popular accounts, Carlisle wanted 64. Ismay thought 64 boats would clutter the decks and decided on just 16. “Besides,” Ismay is reported to have argued, “with Thomas Andrews at the drawing boards, she is practically unsinkable.” Famously, Carlisle quit that very day, while at the official inquiry later, Ismay denied ever having had the conversation. Belfasters’ response to the disaster: “She was all right when she left here.” “That’s what comes of giving our ship to an English captain, a Scottish navigator and a Canadian iceberg,” says Andrew. The Canadians retort that up until 1947, the part of Newfoundland where the Titanic sank belonged to the British so, in fact, it was a British iceberg that did her in.

From the wharf, we see Cave Hill with its distinctive profile of a sleeping giant, thought to have inspired Jonathan Swift’s giant in Gulliver’s Travels. On a clear day, it’s also possible to see the Mountains of Mourne to the distant south, said to be the inspiration behind Belfast-born C.S. Lewis’ Narnia.

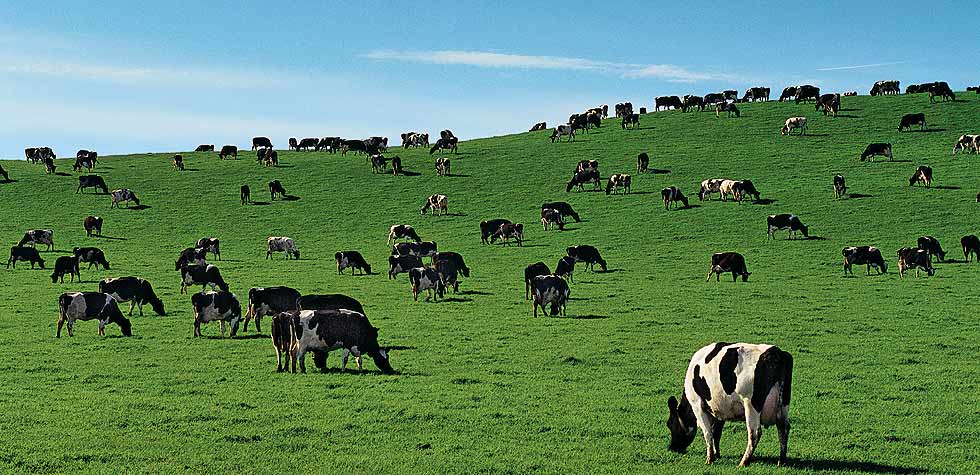

Northern Ireland, the land of the ‘Troubles’, is a revelation. Apart from giving the world C.S. Lewis and an alleged 17 American presidents, it has also undertaken some remarkable regeneration projects since the 1998 agreement. Driving from Belfast to Dublin, we pass through the Drumlin hills, whose rich earth is excellent for rearing livestock, a tradition the Irish take great pride in. In fact, you can’t throw a stone without hitting a cow or a sheep, so our story must pause to take note. First, the secret of their pink health: grass. Green, green grass. And lots of it. If I were any manner of hoofed herbivore, Ireland is where I’d want to live. There are 60 varieties of sheep, and flocks are dabbed in shades of green and red to tell which belong to whom. Andrew admits that he’s told unsuspecting tourists that the red ones are Protestant and the green ones Catholic. I suspect these woolly quadrupeds have few spiritual leanings and are rather bad-tempered to boot. Of all Ireland’s cows, the most curious are the Belted Galloways, black cows with white-striped middles that are affectionately called Belties. The countryside is a patchwork of fields and hedgerows, an expanse of the deepest green dotted with cows, sheep and the occasional wind turbine. Bales of hay fleck freshly harvested fields and we spot a Round Tower, a tenth-century monastic bell tower that served as a safe house.

Passing the invisible border dividing North and South, we reach Dublin. Among the city’s key sights are those connected with its astounding literary heritage. This is the birthplace of James Joyce, Oscar Wilde and three Nobel Laureates — William Butler Yeats, George Bernard Shaw and Samuel Beckett — while Jonathan Swift was the dean of Dublin’s St Patrick’s Cathedral. Statues of Shaw and Wilde adorn Merrion Square, where a commemorative pillar documents Wilde’s more memorable quotes. Across the street at No. 1 is his childhood home, while further away is Yeats’ Georgian residence at No. 82. We pass the Viking-Norse-built Christ Church Cathedral, the picturesque waterfront of the Liffey river and Grafton Street with its famed statue of legendary fishmonger, Molly Malone, who stands with her cart selling “cockles and mussels, alive, alive, oh”. Further south, a sky-blue door and plaque reading ‘Author of Many Plays’ marks Shaw’s birthplace at 33 Synge Street.

Our conscientious hosts have laid on several cultural pursuits. My favourite is a thrilling performance in mime, Man of Valour, which is part of the Dublin Fringe and held at Trinity College’s Samuel Beckett Theatre. Strolling through the grounds, we take in the sixteenth-century colonnaded façades and cobbled courtyards. Our final stop is Ye Olde Abbey Tavern for an evening of traditional Irish music and dancing. Accompanied by fiddle, accordion and guitar, I join in the vigorous quickstep, only to bow out breathlessly after I’m outpaced by a little old lady from Ohio.

Our next day begins bright and early at the Guinness Storehouse. A visit to this stout-lover’s shrine is a morning well spent. Besides, we’re beginning to enjoy drinking straight after breakfast. We learn of Arthur Guinness’ ‘deal of the century’, where he signed a nine-thousand-year lease on a four-acre brewery for a ludicrous £45 a year. We’re shown the magic ingredients — water, barley, hops and yeast — and schooled in the process — roasting-mashing-brewing and so on. The fun and games include pouring ourselves the perfect pint, while the rooftop Gravity Bar affords unparalleled views of Dublin, the horizon rimmed by the Wicklow Mountains from where Arthur procured water for his beloved stout. Most importantly, the entry fee includes a free pint! Back on the road, we pass Tipperary and Limerick counties and finally stop in County Kildare, where prizewinning stallions are stabled at the Irish National Stud. In a country fixated on horseracing, jockeys are superstars. Even if you’re not a race-rat, a leisurely ramble past paddocks where mares, foals and yearlings graze is sheer heaven.

The last leg of our journey takes us to bustling Cork, which was the heart of the world’s butter trade in the eighteenth-century. We pass the Butter Museum and its curious weighing house, ‘the Firkin Crane’, shaped like a rounded butter barrel or firkin. As I stroll through Cork’s lovely English Market, serenaded by Andrew’s unending repertoire of Irish legends while nibbling on homemade cheese, dark chocolate and good old-fashioned Irish baking, I realise I haven’t quite had my fill of Éire-land (and yes, in Old Irish, it’s spelt with an É).

Dublin

Dunluce Castle

Ireland