Somewhere deep down, Himalaya-watchers are often thought of as lonely creatures toiling away in pursuit of their

Although the festival began on the evening of November 1 with an exhibition of the mountain photography of Sankar Sridhar (many of whose exceptional frames have first appeared in OT), and a concert by the singer Rekha Bhardwaj, the main festival got going the next morning. It seemed only fitting to have the four-time Everest summiteer and one of India’s best current mountaineers, Loveraj Singh Dharmshaktu, inaugurate the festival as its chief guest.

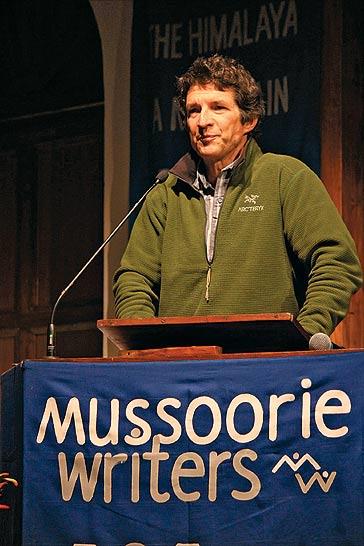

Another Everest veteran, the mountaineer Steve Swenson, opened the festival with a screening of Freddie Wilkinson’s documentary The Old Breed (2012) that got to the heart of the dilemma that faces all mountaineers—what’s the ethical mean and what pushes mountaineers? Chronicling his own ascent of Saser Kangri II in the Eastern Karakoram last year, the movie looks at Swenson and his climbing partner Mark Ritchie’s pursuit of hard climbs well into their fifties. Introducing the movie, Swenson spoke about his personal need to only climb in those places where he can test his own skills, and with partners who start out as his friends, and end the expedition as his friends, because, two-thirds of all summit attempts end in failure. In defining the Karakoram, not only did Swenson describe it as a physical wilderness, but also as a political one; a magical land caught in the crossfire of India, Pakistan and China.

He took up the theme again the next day, this time elaborating on the multiple barriers of bureaucracy that not only prevent climbers like him, but also come in the way of local livelihoods that could benefit from assisting expeditions. Few people know more about the barriers of red tape than Harish Kapadia, a civilian whose career in what is perceived as the domain of the armed forces has been extraordinary. His stories of wrestling with Inner Line.

Permits were witty and enlightening—playing competitive generals against each other for a permit for the Karakoram, the sheer bloody-minded pursuit of ministries—but he did point out that these days it is usually quite easy for Indians to get permits. “If the mountains can’t stop you,” he said, “bureaucracy can’t.”

Dr Charles Clarke straddles the world of mountaineering and medicine, and he’s as well-known for his climbs as he is for his work in neurology and high-altitude medicine. As the co-author with Chris Bonington of best-selling expedition books like Everest, The Unclimbed Ridge, he donned his literary hat on the first day to list his ten favourite mountain travel books. Covering classics like Eric Shipton’s Upon That Mountain and Peter Boardman’s Sacred Summits, as well as the heartbreaking Where the Mountains Cast Their Shadow by Maria Coffey, it was a good, if predictable selection. What was more interesting was his lecture the next day on Tibetan medicine. I was reminded of the murals of the famous medicine Buddhas at Alchi while Clarke described detailed medieval medicine thangkas and how they included sophisticated methods of diagnosis and prescription that can be traced to older Ayurvedic practices.

A variety of people spoke on the cultural aspects of the mountains, like V.K. Sashindran who gave a lecture on mountain philately. What makes mountains national icons? In some cases it could be about a physical feature that has a big impact on a country’s psyche, like Nicaragua’s 1862 stamp of Mt Momotombo. In other cases, to encourage tourism, like Nepal’s set of the country’s eight eight-thousanders from 2004. Funnily enough, India, which has nothing to do with Everest, was the first country to put it on a stamp in 1953.

The anthropologist Viraf Mehta’s talk on the prehistoric petrolyphs of Ladakh was an eye-opener. He spoke about the efforts of his team to unearth and catalogue these strange and wonderful examples of rock-art, the provenance of which are still unknown. Such is our ignorance of things that sometimes lie all around us that, till 1992, experts were sure that there were only about twenty-five such artefacts in Ladakh. Today, thanks to the work of people like Mehta, there are 125, and rising.

The threat to habitats is an issue that is widely acknowledged, and Gulzar’s poetry session on the second day, angrily pointed in its protest against the desecration of nature, lay at the heart of it. In a different way, it informed two talks given by a pair of highly motivated WWF workers on the third day. Pankaj Chandan works in Ladakh in the field of wetland biodiversity, and he spoke of his love for the rare black-necked cranes that breed in the great inland lakes like the Tso Moriri. Rajarshi Chakraborty, who works in Sikkim, gave a delightful talk on that state’s strange and beautiful flora and fauna and the need to learn from local communities in saving this diversity. It was stunning to know that the Chakma tribes have a name for every animal and plant in the state, and that between 1998 and 2008, as many as 353 new species were found in the state.

Padma Shri historian, Dr Shekhar Pathak’s scholarship on the mountains is legendary. His NGO, PAHAR (People’s Association for Himalaya Area Research), is an admirable project to democratise information about the Himalaya. He spoke about the famous Great Game spy and cartographer extraordinaire, Nain Singh Rawat, with material culled from Rawat’s personal diaries from his clandestine surveying trips in Tibet in the 1860s and 70s. At the end of the lecture he pointed out that, along with Harish Kapadia, Nain Singh Rawat remains the only other non-western explorer to be honoured with the Royal Geographic Society’s Patron’s Medal.

A mention must be made of the delightful concert by the Tetseo Sisters from Kohima who had the audience eating out of their hands at the end of the second day with their performance of traditional Naga songs called Li. A bewitching mix of three-part harmonies and 60s girl groups, the sisters personified the easy grace that we attach to mountain communities everywhere.

The final day was reserved for an inaugural Mussoorie half-marathon, from Gandhi Chowk to Everest House and back to Woodstock school. It fell on Mussoorie’s own Bill Aitken to conclude the festival. He arguably had the best line of the festival: “George Mallory implied, in a bloodless Saxon way, that we’re drawn to mountains because they’re there. I would say that we go to the mountains because they’re bloody marvellous!”