Seen from the air, Kabul is something of an anti-climax, coming as it does after the dramatic

More than anything else, it is encounters like these that most accurately describe the experience of visiting Kabul. The city both challenges and conforms to its stereotypes, with its bullet-marked walls and SUVs trapped in monster traffic jams, its swish French eateries selling foie gras and the children on its roads who beg in all the official UN languages but accept baksheesh only in US dollars. A city that has existed for over 3,000 years and has survived three decades of war, Kabul is both ancient and alive, and welcomes visitors with a mix of gallows humour-inflected courage and an unabashedly lavish affection for the mehmaan.

The past few years have brought changes at breakneck speed here. The influx of people and money coupled with the rise in insurgency has led to a transformed landscape. Glittering malls and wedding halls have mushroomed but much has also vanished behind barricades and security cordons. Even in what remains, however, there is plenty that is both picturesque and vibrant. One such spot is the Shah-do-Shamsher (King of Two Swords) mosque near the Kabul river. It was built by King Amanullah to honour the shrine of a seventh-century Muslim warrior who fell fighting with a sword in each hand. The legend around the mosque is a familiar one of miracles and stubborn saints. When workers tried to tear down the shrine for road expansion work in the 1920s, they were constantly held up by accidents and ominous signs.

The collection at the recently restored National Museum dispels the myth of an ‘always Muslim’ Afghanistan. Finally, Amanullah not only let the ziyarat stand but built the two-storey mosque to honour the martyr. With its yellow walls, fluttering mass of resident birds and baroque-style architecture, the mosque has an air of serenity that is untouched by the dense traffic around it. It also sees sessions of Sufi gatherings, with music and hypnotic chanting as the devout move their heads and their bodies to the rhythmic beat.

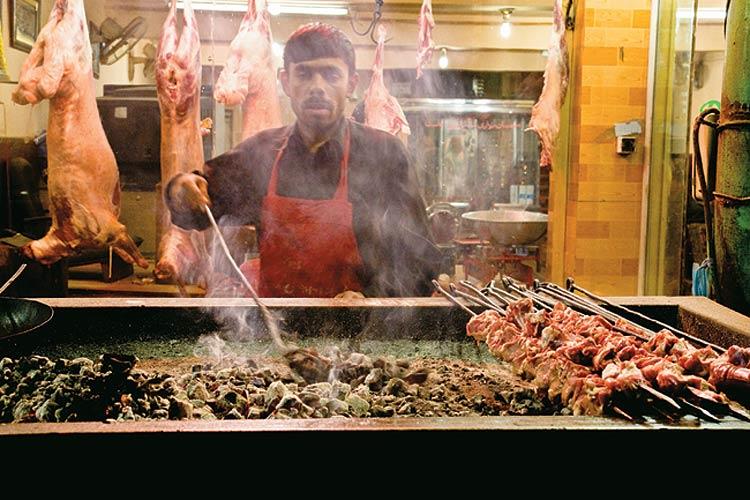

This is the old part of Kabul — a maze of narrow alleyways lined with tiny shops selling azure, spices and fighting birds. At old-style sarais and restaurants lit by fluorescent tube lights, ghostly figures roast kababs on smoke-filled terraces. It is an area best seen on foot, to allow details of architecture and glimpses of everyday life to unfold. There are signs of once-beautiful neighbourhoods here, in skeletons of traditional mud and timber houses and shattered balconies with delicate latticework. There are also echoes of the courtly manners of a bygone era. Everywhere we go, shopkeepers and residents offer us cups of green tea, ask us to share their afternoon meal, invite us home to have dinner with their families. “Please,” they say, raising their hands to their hearts in a gesture familiar to Afghans, “you are our guests.”

The main road cutting through here is Jade Maiwand, a wide boulevard that was created in the late 1940s as a ‘modern’ Oxford Street-style area to counter the clutter of the old city. But the area was at the frontlines of the civil war, and suffered heavily under rocket attacks and shelling. Ironically, one of the hardest-hit places was the historical musicians’ quarter of Kharabat. The neighbourhood was established in the 1860s by Amir Sher Khan, who brought Indian musicians from Kashmir and Punjab to his court. These mingled with the Afghan hereditary musician families to create the distinctive Kharabati style of music. Most Kabuli musicians can trace their roots to this narrow road, which illuminates the memories of those old enough to recall a time of peace. At night, the street would be alive with colour, merriment and music, giving it an edge of notoriety. This is reflected in one of the meanings of ‘kharab’, as being a place where bad or naughty people live. It also refers to someone who spends too much money in having a great time with his friends; ‘have a kharabat’ roughly translates to ‘let’s go have some fun’. Residents, however, prefer to link the name to the Sufi traditions brought by the earlier ustads from India. “Sufis refer to their gatherings as kharabat, or temples of ruin, since they believe the material world must be destroyed to gain enlightenment,” says Ustad Hamahang, our guide through this street.

One of the more famous musicians on the Kabul scene through the 1960s, Ustad Hamahang grew up listening to “the dhap of tablas and the scraping of rubabs” in Kharabat. So great was his popularity that he was once mobbed by a large crowd of women after a concert at the Bagh-e-Zenana (Women’s Garden). The huge mass of female fans lifted his white Russian-made Volga off the ground. He finally made an exit through a back gate, with the car laden with flowers flung at him by adoring matrons and young girls. Like most bacha-e-Kharabat, Hamahang was forced to leave for Pakistan in the nineties, returning only four years ago to his mitti, or home.

Today, overcrowding and rising rents have moved most musicians to the nearby Shor Bazaar, a raucous market that used to be the centre of the spice trade, dominated by the city’s then sizeable Hindu and Sikh community. Bright hand-painted signs point the way to musicians’ ‘offices’, where groups sit rehearsing or just relaxing over tea. There are also several workshops where instruments are manufactured and sold, including beautiful rubabs carved out of mulberry wood, inlayed with silverwork. A good rubab can cost anywhere between $1,000 and $5,000, selling mostly to musicians living abroad. Inside the buildings, away from the din of the road, are tiny one-room music schools. Young children run up the stairs importantly, with their tablas tucked under their arms. Some, exhausted after a late-night performance and a day at school, snooze on the thickly carpeted floor. Most students and ustads alike have recently returned to Afghanistan after years of exile. “Everything has changed,” says one ustad who has returned to Kabul after twenty years abroad, “but our music is still the same.”

The edge of Kharabat and the old city is topped by the majestic Bala Hissar, or High Fort, perched on the Koh-e-Sher Darwaza (Mountain of the Lion’s Gate). There has been a fort on this lofty spot since at least the fifth century, being built on and destroyed several times right until the civil war. The string of rulers the site has accommodated included a young Zahir-ud-Din Babur, who entered the city with a ragtag band of soldiers and went on to establish Mughal rule over India. Babur provides a vivid account of the citadel as being of “surprising height and enjoy[ing] an excellent climate, overlooking the large lake and three meadows which present a very beautiful prospect when the plains are green”.

The fort is now a base for the Afghan National Army and the view is also different. But on the day we visit, spring showers have washed away the dust that usually covers the city, touching it with a soft light and patches of the greenery that Babur loved so much.

Babur was one of Kabul’s most constant admirers and wanted to be buried there. His wish was carried out nine years after his death, when his mortal remains were moved from Agra to Kabul by his widow. The Bagh-e-Babur, on the slopes of the Koh-e-Sher Darwaza, has been beautifully restored by the Aga Khan Trust for Culture and has become a popular public spot since it reopened in 2008. The sight would probably gladden the heart of the merry Mughal, who spent most of his time in India bitterly complaining about the heat and dust. Afghan families sprawl across the lawns, enjoying lavish picnics of kababs and watermelons next to streams of bubbling water, under the shade of apricot and cherry trees.

In the rush of media descriptions of Afghanistan, it is easy to imagine it as a country that was ‘always’ Muslim. The collection at the recently restored National Museum, though sadly depleted by years of war and looting, dispels this myth with its beautiful Buddhist sculptures, relics from Greek and Kushan kingdoms and an arresting head of the goddess Durga. The huge black marble basin that stands at the entrance alone makes the museum worth a visit. Decorated with Buddhist motifs and Islamic texts, it was used to serve juice to devotees at the shrine of Mir Wais Baba at Kandahar. This being Afghanistan, even the museum has a thrilling tale to relate. According to the director, Omara Khan Masoudi, who has worked here for over twenty-five years, when the Soviets withdrew from Afghanistan, the worried authorities split the museum’s collection into two and hid part of it in a secret vault somewhere in the city. In the years that followed, the museum was looted and destroyed by both the Mujahideen as well as the Taliban, who destroyed all human figures. The status of the hidden artefacts remained unknown. “For years, we watched in suspense but kept our mouths shut,” smiles Masoudi. Finally, in 2003, the secret vault was opened and 22,000 priceless pieces of Afghanistan’s heritage emerged, untouched.

The museum is located across the road from one of the most photographed spots in the city—the Darul-Aman palace. Built in the early 1920s by King Amanullah as part of his efforts to modernise Afghanistan, the neoclassical building was heavily damaged in the fighting between rival Mujahideen factions in the nineties. It is now off-limits to civilians, though children play football in the adjoining grounds. The palace was linked to Kabul through a narrow gauge railway run by three small steam locomotives that the king bought from Germany. One of these Henschel engines now stands outside the museum.

More than ruined palaces, however, a real sense of the city is to be found in the rhythms of its everyday life, which persist, bloodied but unrelenting. It is in the buzz on the streets of Shahr-e-Nau, where young Afghans come to shop, eat pizza at the roadside stalls or, in the manner of youth everywhere, check each other out. It is in the fast vanishing houses of old Kabuli families, with their high walls hiding green lawns, lush fruit trees, large windows and sun-filled rooms. It is in the unthinking remark of a woman who never left the city but finds herself an outsider. “When I walk into an office, I don’t see anybody I know,” she says, echoing a sentiment of loss that resonates with Kashmir’s pundits, the shurafa of Old Delhi, Palestinian refugees dreaming of their orchards in Nablus.

On our last evening in Kabul, we head to the mausoleum of Nadir Shah on Teppe Maranjan, overlooking east Kabul. The spot is crowded on holidays and at Nauroz there is a kite-flying festival here, but on the day we visit it is relatively empty. A grizzled old man naps in the mild sunshine, a car-load of young men listen to music on their radio and a group of boys comes out to fly kites from the edge of the cliff. We watch the colourful shapes rise and dip over the city, framed against the snow-capped mountains that glow with the light of the setting sun. As dusk falls, we take a taxi back to our guesthouse. The driver, a young man in his twenties, switches off his radio as we pass the fluttering green flags of the martyrs’ graves and talks of Bollywood and years spent in exile, and a cousin who died in a suicide attack. At our destination, we try to count out the money for his fare but he presses it back. “Please,” he says, putting his hand to his heart, “please, you are our guests.”

The information

Getting there

Indian Airlines runs direct flights from Delhi to Kabul four times a week (from Rs 32,000 return; indian-airlines.nic.in), and Ariana Afghan Airlines thrice a week (from Rs 13,000; flyariana.com). Private Afghan carrier Pamir Airlines flies daily (from Rs 15,000; pamireticket.com) and Kam Air thrice a week (from Rs 14,000; flykamair.com).

Visa & permits

Visas for Indians are available gratis from Afghan consulates in Delhi and Mumbai. Afghanistan is one of the countries for which Indians need emigration clearance, so secure it beforehand from the office of Protector of Emigrants or ensure your passport has an ECNR stamp.

Getting around

Private radio cabs offer a safe and comfortable ride for $3-5. Or hop into a yellow local cab ($1-4, depending on distance) with good conversation for free. Buses do ply but these aren’t geared to deal with tourists.

Where to stay

The Kabul Serena (from $281; serenahotels.com), in the place of the old Kabul Hotel, is a beautifully designed building with an improbable air of calm and Kabul’s only health spa. Repeated attacks have led to beefed-up security for its high-powered visitors. The Intercontinental Hotel (from $100; intercontinentalkabul.com) saw its heyday in the seventies, hosting guests like Feroz Khan and Hema Malini, besides Kabul’s swish set. It retains a somewhat faded charm in the retro-style disco and always-sensational view. The Gandamack Lodge (from $90; gandamacklodge.co.uk) offers Raj-style décor, full English breakfasts and body armour for rent. The Hare and Hound Watering Hole in the cellar is a favourite with foreign journalists. Heetal Plaza (from $80; heetalplazahotel.com) is a swish new ‘eco-friendly boutique hotel’ in the expat-dominated Wazir Akbar Khan neighbourhood and is owned by the son of a former Afghan president.

Budget hotels are hard to come by, especially if you need generator backup and security. The nicest guesthouses are converted Kabuli homes with big gardens. The Kabul Inn ([email protected]) in Qala-e-Fatahullah or the Le Monde Guesthouse (lemondeghkabul.blogspot.com) at Shahr-e-Nau offer good value-for-money stays from $55-65 a night. The Salsal Guesthouse (+93-79-9734202), near Shahr-e-Nau park, is the pick of the backpack scene, with rooms from $10-20 and shared bathrooms.

What to see & do

Kabul is an ancient city and despite the desolation and wreckage of war, there is plenty to see and do here. While it is mostly safe, be prepared for unexpected events at all times. Start with the Bala Hissar, perched on the edge of the Koh-e-Sher Darwaza. The ancient city walls also begin from here, and a trek around the ridge offers many beautiful views. Stick to well-beaten paths to avoid nasty surprises (of the landmines and unexploded ordnance variety). Near the southern edge of the Bala Hissar is Kucha-e-Kharabat, the old musicians’ quarter, and Shor Bazaar, where most musicians have their offices now. Check out the kite shops and spice stalls here, before heading to Jade Maiwand, designed as an Oxford Street-style boulevard. Don’t miss the fascinating Kucha-e-Ka Faroshi, where a huge range of birds are sold, including fighting partridges or kowk. The Aga Khan Trust for Culture has been at work in the old city, restoring key buildings in the historical neighbourhood of Asheqan va Arefan, including a traditional hammam and mosque. These are worth a look, as is the restored mausoleum of Timur Shah and the gardens around this eighteenth-century structure, which is surrounded by a bustling market.

Cross the river towards the Shah-e-Do Shamsher mosque and admire its ‘Afghan-baroque’ architecture and the beautiful riverfront buildings nearby, while feeding the birds that flock around.

Enjoy a walk through the expertly restored Bagh-e-Babur (entry 100 Afghanis; Re 1=0.9 Afghani), the largest public open space in Kabul, with flowing water and shady trees. Fridays are a good day for visiting the National Museum (20 Afghanis) for a glimpse into the region’s rich history, with exhibits from the Greek and Kushan empires. Across the road is the shattered beauty of the Darul-Aman Palace, built by King Amanullah in the 1920s as part of his short-lived modernisation drive (you can’t go in, though). The National Gallery of Art (250 Afghanis) at Asmai Watt has a collection of both old and modern Afghan artists, and is housed in a beautiful old building.

Nadir Shah’s mausoleum on Teppe Maranjan is a favourite spot for kite-flying, especially during the spring festival of Nauroz. On the way down, visit the OMAR Land Mine Museum (there’s a charge for cameras; they accept donations, but there’s no fixed fee; mineclearance.org) run by the Organisation for Mine Clearance & Afghan Rehabilitation; it displays Afghanistan’s chilling heritage of landmines, rockets and bombs.

For shopping, head to Chicken Street, where the shops bristle with traditional handicrafts, carved wooden furniture, lapis lazuli and silver jewellery. Flower Street has DVD stores, bakeries and shops with imported food. The shopkeepers love to talk, so spend some time sipping tea and you may end up with a bargain. There are plenty of carpet shops on Chicken Street, but do visit Nomad Carpet Gallery in Qala-e-Fatullah. The owner, an award-winning designer, works with craftsmen to create stunning contemporary designs on his rugs. Ganjina near Insaf Hotel at Charahe Ansari is a collective of Kabul’s choicest designers, where you can pick up woven bags, embroidered cushion covers, silk jackets and wine bottle burqas in one spree. Check out the lovely silk scarves with Persian calligraphy at Zarif (zarifdesign.com). The Shah M Book Store (shahmbookco.com) at Charahe Sadarat is perfect for browsing, with the genial owner Shah Muhammad Rais providing helpful tips and tea. Possibly the only English book on Afghanistan not in his well-stocked store is The Bookseller of Kabul by Norwegian journalist Åsne Seierstad. Rais sued her for breach of privacy.

There are several places that are a short drive from Kabul and are well worth a visit. Qargha, the picturesque manmade lake surrounded by mountains, just 12km from the city, is every Kabuli’s favourite picnic spot. There are kabab shops, motorboat rides and even a new golf course. Take a day trip to the Panjshir valley, 150km north of Kabul, on a road that follows a rushing river and lush fields dotted with the wreckage of helicopters and tanks. Drive up to the mausoleum of ‘national hero’ Ahmad Shah Massoud, being reconstructed on a grand scale. The riverside restaurants offer great views and lavish lunches of pulao and fried fish. The scenic village of Istalif, about 18km from Kabul, may have been named by Alexander’s soldiers who camped here in the fourth century. There are beautiful views of the valley from the Takht-e-Istalif. The charming bazaar is famous for traditional glazed Afghan pottery.

Where to eat

Kabul is a great place for eating out, thanks to the buzzy expat scene. Don’t be intimidated by the bulky security guards at the gates. Keep your passport handy if you fancy a drink — only non-Afghans can be served alcohol by law.

Sufi Restaurant (sufi.com.af), near Park Cinema, serves hearty Afghan soups, manto (meat dumplings) and Kabuli pulao, with live Afghan music by traditional Kharabati artists thrice a week.

Haji Baba at Shahr-e-Nau, near Chicken Street, has some of the juiciest kababs in town. Also sample their excellent breads.

Herat Restaurant, near Park Cinema, has honest-to-goodness Afghan food in a no-fuss setting. Their kababs were reportedly relished even by the Taliban.

Le Divan Restaurant (latmospherekabul.blogs.com), formerly L’Atmosphere in Qala-e-Fatullah, is the giddy heart of the city’s expat scene. The menu is French, but the real draw is the outdoor pool.

Le Bistro, behind the Ministry of Interior, has a more relaxed vibe, a beautiful garden and an excellent bakery. Try the fresh croissants and lemon tart.

Flower Street Cafe ([email protected]) is somewhat confusingly named, for it is actually on Qala-e-Fatullah, and has a shady garden nook, good bakes and fresh coffee.

Cabul Coffee House, in Qala-e-Fatullah, was started by Kabul Beauty School author Deborah Rodriguez. It has sandwiches, coffee, juices and Wi-Fi for its many customers tapping away on their laptops.

The Grill, a popular Lebanese place at Wazir Akbar Khan, has tall glasses of lemon-mint coolers, mixed grill platters and fresh fluffy white bread of the kind that is hard to forget. Sit out in the lawn if you fancy a sheesha.

Istanbul Restaurant, at Macroyan near Massoud Circle, has excellent Turkish food and is a popular lunch spot for the office crowd. Eat out under the towering trees, or enjoy the quirky décor inside. Try their baklava, or visit the confectionary shops around Shahr-e-Nau for creamy Iranian sweets.

Top Tip

Organisations like Turquoise Mountain (turquoisemountain.org) and Foundation for Culture and Civil Society (afghanfccs.org) organise plays or concerts regularly, especially during the summer; check their websites for updates.

Afghanistan

Bala Hissar

Darul-Aman palace