As soon as we arrive in downtown Buenos Aires, I understand why it is known

Tango is my reason for coming here. To say that I am interested in tango is a serious understatement. Nobody who dances tango is merely ‘interested’ by it. All tango dancers outside Argentina are tango lunatics. Take me, for example: I live on a constant bank overdraft of existential proportions and yet I have come all the way to South America to spend ten days blowing money I don’t have on an extravaganza of dancing and grilled meat.

There is no other city like Buenos Aires in South America. It is populated by the descendants of Italian, Spanish, English, Jewish and German immigrants who started flooding Argentina from the mid-nineteenth century onwards and never quite got over their European nostalgia. This is the world capital of psychoanalysis and eating disorders, a place as expensive as New York and culturally as rich as Europe’s capitals.

I am here for the international congress of tango. It is an annual event, to which tango lovers from all over the world throng for a week of classes with the best dancers of New Tango. The cost is twice the regular price for locals and I’m beginning to have doubts. Still, I decide to go to the opening night of the congress, to see whether there are any irresistible foreigners there who can sweep me off my feet.

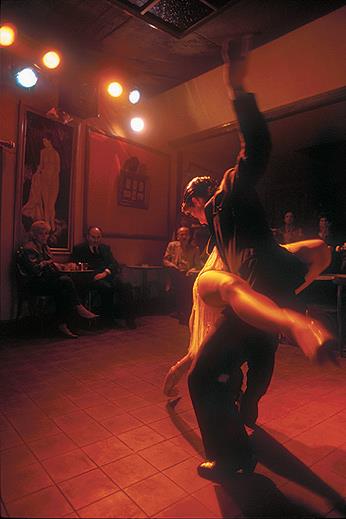

The three principle organisers of the event dance with their partners. Two of them featured in Sally Potter’s acclaimed The Tango Lesson and are now celebrities. They perform to the music of Astor Piazzolla, the genius of modern tango who created complex orchestral music of great intensity and pathos. These dancers represent the new generation of tango or tango nuevo; their choreography is characterised by movements of dazzling precision, a stylised, sterilised abstraction of desire or violence. There are no expressions on their faces. They are unbearably glamorous, their virtuosity has a hall-full of tango fanatics gasping. But where is the passion, the humanity of old tango danced in seedy streets by drunk poets in bowler hats and tragic whores with red mouths? Not here. This is the avant-garde of tango: a dance of estrangement, not intimacy, of alienation, not passion, of force, not delicacy. Tango for men with long hair and earrings and androgynous women in trousers: tango for the twenty-first century. The dancers end not in a convoluted embrace, but at opposite ends of the dance floor, facing away from each other as the final chord of Piazzolla’s Violentango crashes. The effect is devastating. The audience falls at the feet of their gods. I weep.

Next to me sits a fellow weeper, an ironic, lively fifty-year old painter from Buenos Aires who is introduced to me as the ‘official artist’ for the congress. Guillermo creates pieces of public art by dipping his shoes in black paint, his dance partner’s in red — and tangoing on a canvas, painting their dance. His art has drawn international attention (and was even featured on CNN).

During the course of the night, I dance with a grim, moustachioed Italian who squeezes me so tight I have no breath to tell him so; a tall, bleached German whose staccato movements make me hate tango for an entire five minutes; a skinny Chinese who apologises all the time for his mistakes; a sweaty Peruvian who tells me sternly that I must practice my waltz and abandons me… But before I flee, I dance with Guillermo — and I see the light. Guillermo belongs to the old school of milongueros (tango dancers) who prefer a simple, intimate style, devoid of formal training. And they have that elusive quality that none of the foreigners here possess: soul. It is intangible, it has nothing to do with how you look or how many moves you know. It has everything to do with how you listen to the music, how you relate to the person you are dancing with, how you feel about being here, in the moment. It doesn’t look spectacular, but it feels amazing. That is the soul of tango. I decide to split from the group, flee the congress and seek my fortune elsewhere.

Tango may be known as just a dance in the rest of the world, but in Argentina it is a culture. There are two specialised tango magazines published every month, listing classes, milongas (dances) and everything that goes with the business of tango: shoes and clothes, photo studios, even osteopaths for injuries!

San Telmo, an arty suburb, hosts spontaneous street tango shows by professionals and amateurs. And, by a stroke of luck, I catch the last performance of Piazzolla’s Concerto for Bandoneon at the Teatro Colon, an architectural giant and cultural icon. Listening to the third, frantic movement of the concerto played by the National Symphony and fiercely dominated by the lament of the bandoneon, I succumb to my weak nerves and—yes, you guessed it—weep again. It has only been twenty-four hours since the last time! A fellow New Zealander beside me, a sensitive guy and consummate tango-fanatic, joins in.

What is it about tango music that makes people break down in public? What is tango? Why become obsessed with it? Why not salsa or flamenco? “Tango is a sad thought that can be danced,” said the Argentine poet Discepolo. A blend of Italian and Spanish music and Latin American lyrics, tango was created in the 1880s and became world-famous through the songs of French-born Carlos Gardel who exported it to Europe before the cultural snobs of Argentina embraced him. In the words of my new acquaintance Guillermo, tango expresses the principal sentiments of both the European immigrant and the gaucho displaced by the Europeans — nostalgia, sadness, melancholy and bronca (a very Argentine term denoting irrational anger). From the early, populist songs to the new, complex orchestrations of Piazzolla and Pugliese, tango has survived as the music and dance of the dispossessed. It is a song of longing, loss and exile, and it is precisely the vastness of these concepts and the infinite variety of human experience within them that is so hypnotic for some.

In the ten days that I spend chasing after the best teachers of tango in town and going to milongas — which don’t start until midnight and don’t end before 4am — I live in a blur of sleeplessness, melancholy music, and the ephemeral embraces of strange men in semi-dark, seedy night-halls. The tango scene is complex and you must know where to go. There are dances in clubs every night and some of them are conservative and closed to outsiders. I spend one night sitting at a dance-hall full of middle-aged couples and groups: characters out of a Fellini movie. Women of sixty with super-mini skirts, enormous hair and jewellery so shiny it hurts to look at it, dancing with immaculately turned out gents with creaky joints; young willowy women with splits in their skirts all the way up or tight trousers that start way below their pierced belly buttons (the women of BA are among the most beautiful in the world). Here are stunning dancers who have danced every night of their life for decades, rubbing shoulders with appalling, hopelessly club-footed tango-lovers who will never give up; the wrinkled, trembling, old dancing with the vulgar young; the enormous with the anorexic; the tobacco-stained Peruvian immigrant with the plastically enhanced woman of society. Tango is a curious equaliser, an obsession that transcends boundaries. Tango should be danced like a one-night stand, the Code says: with absolute passion, but without a future. Even after wrapping your legs around a stranger, it would be unusual for him to ask for your phone number, no matter how sticky with your sweat and perfume he is. It is a Code written by men: tango is a male-led, male-initiated dance which postulates that an invitation to dance is offered by a flicker of the eyes and accepted by a barely perceptible nod. Thus, I see a woman next to me get up and walk towards a man who is advancing from the other end of the hall: they have exchanged The Glance. It’s a thrillingly old-fashioned device. Experienced male dancers generally have the snobbery to wait and see you dance with others before they decide whether you are worth the glance of invitation. I spend hours beholding in my peripheral vision statuesque tangueros lurking in dark corners, watching me wait and never moving my way. It’s tough on the BA tango scene — but worth it.

After a week of dancing the darkest of Latin dances, I’m surprised to discover that I haven’t done anything self-destructive. Instead, I go shopping. In Flabella, a famous shop for tango shoes, I spend an hour trying to decide which pair to buy. As my finale, I discover a music shop. The gentle assistant casts an eye over my load and inquires whether I’ll be able to pay my rent for the next few weeks. “No,” I say dramatically, “I’ll live in misery. But I’ll have Piazzolla.” He understands.

The information

Getting there:

As there are no direct flights from Indian cities to Buenos Aires, a good option is to fly British Airways via London (from approx. Rs. 90,000 return; flight time 32hrs).

Where to stay:

It doesn’t get more exclusive than the Alvear Palace Hotel (from $416; +54-11-48082100, alvearpalace.com). Good mid-range options include the Park Plaza (from $90; 67770200, parkplazahotels.com), which presents grand French colonial interiors; the Savoy Hotel (from $138; 43708000, savoyhotel.com.ar); and Lina’s Tango Guesthouse ($75; 43616817, linatango.com) for tango fanatics.

Buenos Aires

dancing

Latin America