Escaping a Delhi summer is too tantalising to turn down, but the sight of Tripura’s rolling green

After a day wandering about Agartala, we were on our way up to north Tripura to the town of Kailashahar through the densely forested hill ranges of Baramura and Teliamura (mura means head). These verdant forests, extremely troubled not so long ago, are home to some of Tripura’s indigenous tribes — the Lushai, the Jamatiya and the Reang, among others. The winding hill road then descended into the lush rice-growing valley of the Manu river, home to the millions of Bengalis who first came here as refugees from neighbouring Bangladesh. The land is folded, with even a few scattered tea gardens. Leaving NH-44 and heading towards Kailashahar, we were in hilly country again. Deep in these forested hills bordering Sylhet lies one of the crowning glories of Tripura’s cultural heritage.

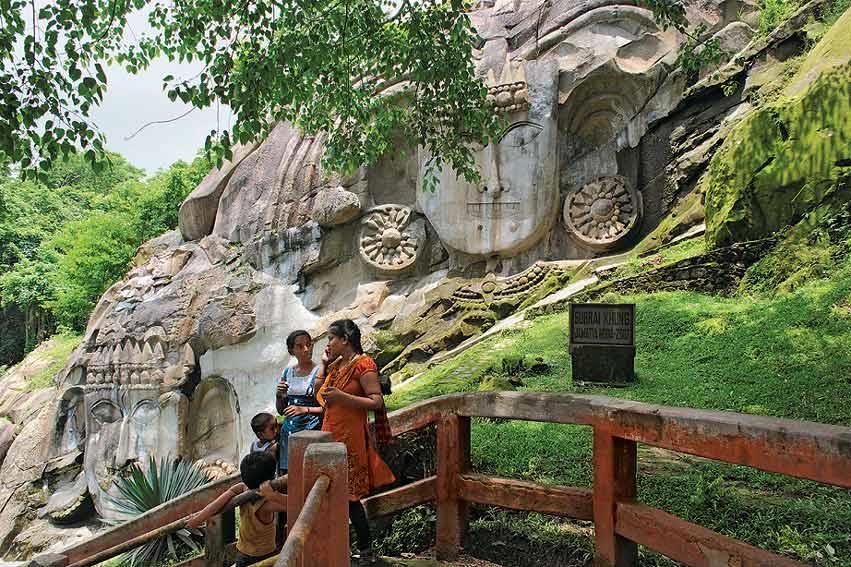

No one can tell with any certainty the identity of the people who created the unique sculptures of Unakoti hill in the secluded valley of the Chawra stream. We arrived on a hot and humid Sunday afternoon. Entire families of Bengalis and Reangs from Kailashahar and the neighbouring city of Dharmanagar were out in force, taking in the sights and offering puja. The object of their veneration was a stupendous thirty-foot bas-relief of a Shiva face, locally called the Unakotishwar Kalbhairava.

To suddenly encounter it is a shock. A cursory view convinced me that I was looking at a giant Buddha face, what with the shape of the head and the gigantic ears. Then I noticed the third eye. And then I saw the massive earrings, distinctly tribal, the slightly showy moustache and the un-Buddhist toothy grin. And finally the ten-foot long crown, reminiscent of both classical Tamil sculpture as well as the face sculptures of the Bayon temple in Cambodia. This image, along with two other similar faces on an adjacent wall, and another collapsed one, forms the cornerstone of this amazing valley. Although their antecedents are not known, informed guesswork by historians suggests that these faces are the centrepiece of a memorial gallery for a now-forgotten tribal king who probably identified himself with a totemic deity, Shibrai, the ur-Shiva of Tripura. Shaivite and Vaishnavite cults had been firmly established among the tribes of the Tripuri hills by the ninth century, vying for patronage with a strong Buddhist tradition.

Further uphill lay a plethora of images, large and small, including a charming little grinning archer with a crown of feathers and two giant female figures of astonishing vitality. The lack of historical information has given rise to many myths, including the widely accepted one that the word Unakoti (one less than a crore) refers to the number of petrified Brahminical deities that lie in this valley, cursed by Shiva to remain here till eternity for some minor infraction. However, what can be asserted with some certainty is that these sculptures span a period of three hundred years from roughly the ninth to the twelfth centuries AD.

This is evident in the range of carving styles. A little further down the valley, the stream descends in a small waterfall, and flanking it is a massive seated Ganesha, along with two equally huge standing elephant-headed figures. You could call them Ganesha figures, except that unlike that cuddly Puranic god beloved of merchants, these menacing forms had up to six tusks each. They were quite different from the figures of the upper pavilion if still tribal in their attire. A little to their left was a discreet standing Vishnu, of even greater technical sophistication. It’s all extremely dramatic, and it’s very tempting to wonder just how many more sculptures might lie hidden in the surrounding forest, and how many more have been irreparably lost in the intervening millennia.

Tripura’s forested hills hide many such secrets, such as the rock murals of Devtamura. These panels lie in an extension of the Baramura range in south-central Tripura. The river Gomati cuts an impressive gorge through it, on its way past the old capital of Udaipur and beyond to the Meghna river in Bangladesh. We got there a couple of days later from our base in Udaipur. Villagers in Amarpur, the closest town, pointed us to a rough track heading into the forest and our much-abused Alto bounced off to a Jamatiya tribal village. This fiercely proud Tripuri tribe, like most of their brethren, are nominally Hindus. But the religion they follow is deeply animistic, one shared by the other Kok Borok-speaking tribes of the state. The supreme deity is the male Matai Katar, who with his equally powerful consort Matai Katarma controls the well-being of the people.

When we reached the Jamatiya village deep in the hills it was past noon, and the stifling, still heat of the forest seemed like some malevolent entity intent on sucking the life out of us. After much pleading — the villagers were understandably more interested in a siesta than sailing — two Jamatiya brothers agreed to take us down the river in their fishing canoe so we could admire the panels. The first panel is actually a massive one, on a sheer rock wall that rises up straight from the river into the surrounding forest, sometimes called the Panchdevata panel. Another panel featuring thirty-seven deities had long succumbed to the combined forces of sun and rain, but somehow that made them more appropriate to the setting — suggestive, autochthonous deities presiding over their kingdom of deep forest and snaking river.

Sailing on the brown, sluggish Gomati thick with silt was hard going, considering Puneet and I were overdressed for the occasion. The brothers’ uniform of bare torso and lungi was far more appropriate. But the magnificent forest soon held us in thrall. In the humid hush of the noonday sun, the giant tree ferns, extensive climbers, orchids and bamboo thickets glistened, giving the impression of living entities brooding by the water’s edge. The silence, broken by the crashing of some unseen animal in the bamboo thickets or the cry of a kingfisher, was all-pervasive. The younger brother rowed, pushing the canoe along with the help of a long bamboo pole. The depth of this sluggish river was only five to six feet, as evidenced by two groups of boatmen we passed on the way, treading the muddy bed of the river to catch fish.

An hour’s boat-ride brought us to the pièce de résistance of this mysterious land — a large rock-cut goddess figure poised with a trident much like Durga, but with a flowing mane like Medusa. Its sudden appearance from the thick canopy of the forest took my breath away. I’ve never been much impressed with Sanskritised names, so when the elder brother told me in hushed tones that they call her Sakragma, or the ghost woman, it seemed more apt somehow. Again, the exact provenance of these sculptures is unknown, but the local legend goes that one of the Manikya kings of Tripura, Amar Manikya, was engaged in warfare with a king of Myanmar, when his army took shelter in these forests. Following his victory, he ordered the carving of these sculptures. Through a comparative study of coins and other artefacts, these can be dated to the fifteenth century. Although created by royal decree, the sculptures are certainly tribal in form. In fact, art historians have been able to find traces of the traditional dress worn by Reang women in the Sakragma figure.

But then, the Manikya kings who ruled Tripura for nigh on six hundred years until 1949 were of tribal origin themselves. The officially sanctioned Rajmala, a genealogical history of the Tripura kings posited a lunar line for the ruling family, linking it to the Mahabharata. However, the first ruler of this clan who can be placed with any certainty was a tribal king of possibly Arakan extraction called Cheong-pha, who replaced the ruling Deva family of eastern Bengal and Tripura in the fifteenth century, successfully defended his new territory against the reigning sultans of upper Bengal and took on the Sanskritised monarchical suffix ‘Manikya’.

Udaipur, the old capital of the Manikya kingdom, was once known as Rangamati. Today, it is a bustling city dotted by massive old lakes (or dighis) and equally old temples of great grace and beauty. The Manikyas were great builders, and they were highly influenced by current styles of Bengali architecture, peppered liberally with Islamic motifs and the older tradition of Buddhist stupas. Udaipur has old temples in every corner, although there are some eleven major ones grouped around different parts of the city. The most famous and revered one is, of course, that of Tripura’s patron goddess, Tripurasundari.

We went to Matabari, as it is popularly known, on a Monday evening. The bright red building of the 500-year-old temple, gleaming in the setting sun, cast a blood-red aura around itself. Built in 1501 by one of the most illustrious kings of Tripura, Dhanya Manikya, this Tantric Kali temple is a classic example of Tripuri architecture — a typically Bengali char chaala or four-roofed structure, surmounted with a Buddhist stupa-like crown. People were lining up for the darshan of an old Tantric Kali idol, which was reputedly brought by the king from Chittagong. This is an important shakti peetha like Kamakhya in Guwahati, and is the centre of the shakti cult of the mother goddess in Tripura. Tripurasundari is also a part of the tribal pantheon, known in the native Kok Borok language as Hakwcharmama, one of the main benevolent deities after Matai Katar.

If Tripurasundari is still feted, many others have fallen into disuse. The beautiful group of three temples called the Gunabati guchcha (bunch) were built by the king Govindya Manikya for his wife Gunabati in 1668. These are under the ambit of the Archaeological Survey of India and therefore well maintained, but two more creations of this king’s reign — his palace and a beautiful red Vishnu temple, both on the north bank of the Gomati — have gone to seed spectacularly.

The old palace, and its neighbouring temple, the Bhuvaneshwari, is quite famous as the setting for Rabindranath Tagore’s novella from 1887, Rajarshi, and his dramatic adaptation of it, Bisarjan, from 1890. The Manikya kings, starting with Birchandra Manikya, had a long and interesting relationship with Tagore. They were his benefactors, especially his friend Radha Kishore Manikya, who paid Tagore an annual income, and even financed the Visva Bharati University in Santiniketan. When the penultimate king built a lavish water palace for himself on Rudrasagar lake in west Tripura, it was Tagore who was asked to name it. He called it Neermahal. Tagore, on his part, loved Tripura, travelling there many times and staying for a while.

In part this was possible due to the long cultural contact and extensive geographical contiguity between Bengal and Tripura before 1947. Two things brought this home to me. The first was the dargah of one of the four famous Sufi pirs of Bengal, Badruddin Badri-i-Alam, better known as Shah Badar, who passed through Bengal and Tripura on his way to Arakan and back in the fifteenth century, and his followers set up dargahs in his memory across the region. On the south bank of the Gomati in Udaipur lies one such, called Badar Mokam, dating to sometime in the seventeenth century, also built in the char chaala style as the temples, only without the Buddhist-style dome. Badar is also the patron saint of majhis (boatmen or sailors), and quite characteristically his dargah stands near the ferry-ghat on the Gomati, home to many fishermen.

The other contact is even older, and to see it we travelled south from Udaipur to the town of Jolaibari in south Tripura The unassuming village of Pilak was once the site of an extensive Buddhist civilisation that stretched all the way from Nalanda in Bihar to Pagan in Burma. This region of Tripura and the adjoining areas of Comilla and Noakhali in present-day Bangladesh were at various points under the kingdoms of Samatata, Harikela and Pattikera from at least the fifth century AD till the twelfth century. In the middle of a picture-perfect rural landscape of rice fields and hillocks lay the excavation sites of Shyamsundar Tila, Pujakhol Tila and Thakurani Tila.

Shyamsundar Tila, our first stop, is renowned for the remains of the excavated base of a massive cruciform Buddhist temple that stood here sometime around the ninth century. Excavated in 1998-99 by the ASI, the site revealed some huge sandstone statues of the Maitreya Buddha and other Bodhisattva images, along with a collection of remarkable terracotta plaques depicting scenes from the Jatakas as well as those from the Puranas and scenes from everyday life. The harsh noonday sun couldn’t dampen the thrill I felt standing amid the remains of an ancient chaitya griha. Life, then, must have been much like this, with little hamlets punctuated with paddy fields and forests. Yet it felt like stepping into deep time, when trade and ideas were flowing to and from Bengal, along with Theravada and Mahayana Buddhism. Flourishing under the vassal states of the Pala Empire — the last big patron of Buddhism in India — these regions of Tripura supplied learned bhikkus to the universities of Nalanda and Vikramshila, and priests to Burma.

But more interesting were the reports I got from the caretakers at the sites of ancient statues that had been given away in more ignorant times to random people who misappropriated their cultural heritage to their own ends. Just beside the excavated mound of Thakurani Tila — which was the site of an extensive monastery — and adjacent to other unexcavated sites, is a Shiva temple that worshipped a ninth-century Naga statue. More enquiries led us to the massive, modern Raj Rajeshwari temple in nearby Muhuripur. Inside stood the statue of a unique four-armed Durga, a Ganesha and a Surya, all three from the Pilak site. Even more astonishingly, in the centre was a massive image of the popular Pala-era Tantric Buddhist goddess Cunda, complete with eighteen arms. With crudely painted eyes and a garish gold necklace, it is worshipped as Kali here.

But the final surprise was still the greatest. I had been hearing about the ashram of a local witch doctor who lived in the village of Kalma. He had something I wanted to see very badly. So we wandered into the forest, asking various local Reangs for the ojhabari (house of the witch doctor). Finally, on the outskirts of Kalma village, we found him, a wizened old man, grave and calm. Did he have a temple, I asked. He nodded and motioned to me to follow him. We walked across fields and through a grove of trees to a rough and ready temple adorned with signs of ‘Jai Ma Kali’ and marked with tridents. He washed his feet, unlocked the door, and stepped in. Inside stood a giant apparition. It looked like Kali, wearing a garish red and gold sari. I looked closer: it had a crown of gold, golden painted eyes and even a painted red tongue. But it wasn’t Kali. For a start it had rounded masculine shoulders, the hand mudras were all wrong (Kali never blessed anyone) and it was standing on a vishwa padma (world lotus) pedestal, a Buddhist motif, and was flanked by diminutive statues of Tara. Then it dawned on me: here I was, looking at a 1,200-year-old statue of the Avalokiteswara Buddha! Tripura had surprised me once again.

The information

Getting there

Daily hopping flights connect Agartala via Kolkata to Delhi and Mumbai. For other cities, change flights in Kolkata. The one-way fare from Delhi is around Rs 5,500.

Getting around

Tripura has good roads and the best way to get around is to rent a car with a driver. There are many options but you can contact Asit Bhowmik (9836180038) of Point to Point Tours and Travels. Rates: Rs 7/km; car charges Rs 600 per day, driver charges Rs 100 per day.

Where to stay

Tripura has a good network of state tourism guesthouses. Apart from Agartala, the other hubs are Kailashahar for North Tripura, Udaipur for South Tripura and Melaghar for West Tripura (all from Rs 500 on twin-sharing basis; 01381-2325930, tripuratourism.nic.in).

What to see & do

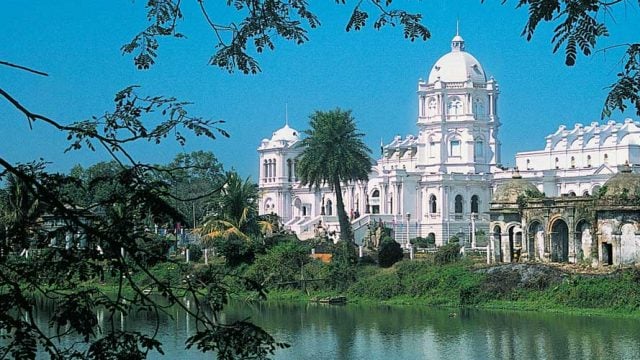

Despite being a fairly small state, there’s much to see and do in Tripura. Agartala offers the Ujjayanta Palace (entry Rs 5), the stunning home of the erstwhile kings of Tripura. It is currently being renovated but even a ramble in its grounds is worth it. Also visit the Benuban Vihara, a modern Buddhist temple, and the Chaturdash Devta Mandir in old Agartala. A visit to the State Museum (entry Rs 2) is also worthwhile. 30km from Agartala lies the Kamalasagar lake beside the Bangladesh border, which is worth a visit for the Kashba Kali temple.

The ruins of the Buddhist stupa at Boxanagar lie 40km south-east of Agartala via Bishalgarh.

In North Tripura, visit Unakoti, 180km from Agartala via Kailashahar. The forest gate at Baramura on NH-44, about 30km from Agartala, opens daily at 8am for vehicular traffic.

The old capital of Udaipur lies 55km south of Agartala. Apart from the Tripurasundari temple, other sights include the Mahadev Bari and Gunabati group of temples next to Mahadev lake and Bhuvaneshwari temple and the ruins of the old palace across the river.

The rock-cut murals of Devtamura lie 30km east of Udaipur. Drive to Chabimura village near the town of Amarpur to arrange for a boat to take you down the river for around Rs 500.

Pilak’s Buddhist ruins are 60km south of Udaipur near the town of Jolaibari. The ruins are situated along three sites, and all three are well marked.

The lake palace of Neermahal is situated 22km west of Udaipur near Melaghar. Ferry charges across the lake are Rs 20 per head. Entry fee Rs 10.

Buddhist ruins of Pilak

Kailashahar

north eastern India