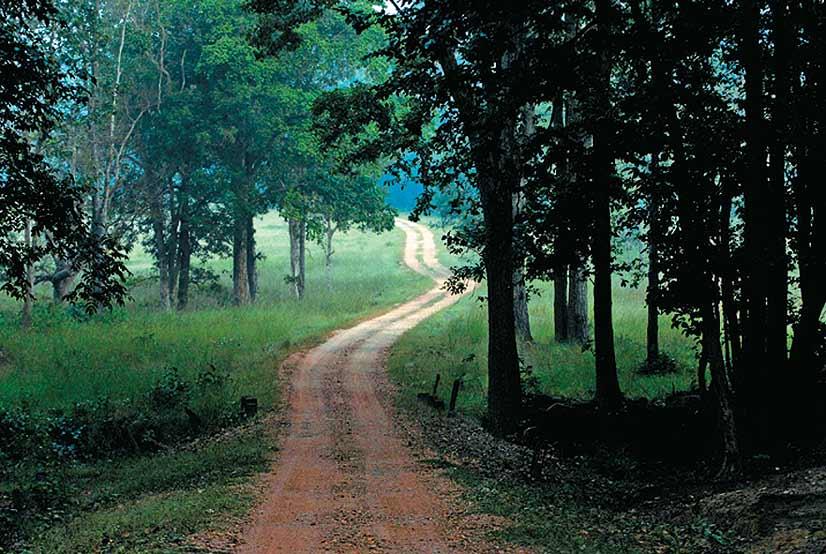

Somewhere deep down they’d known that things would change, that the tranquillity of the sal forests that

For years they’d fought to preserve the surrounding forests, involve people from neighbouring Bhakrakot village in their activities and make the camp as ecologically low-impact as possible. The camp had become a favourite with serious wildlife enthusiasts and naturalists. Shutting down was an admission of defeat to the marauding concrete resorts, with their televisions, discotheques and swimming pools which have, over the last decade, overrun the periphery of the reserve. Once the only camp in the area, Camp Forktail Creek had become one of nearly half-a-dozen, with more coming up.

“We didn’t have much of a choice,” sighs Suri, “All we can hear in camp today are the sounds of excavators and drilling machines at work on the construction of two resorts next to us. It was not the most conducive environment for a wildlife experience.”

What’s happening in Corbett is not unique, and neither is it confined to areas outside the park. Unregulated tourism and development are wreaking havoc in the 39 designated tiger reserves and other national parks around the country, especially those in Central India. It was in tacit recognition of this state of affairs that the Supreme Court, in an interim order passed on July 24, 2012, temporarily banned all tourism in ‘core areas’ of Tiger Reserves.

The case has its origins in a Public Interest Litigation (PIL) filed by a Bhopal-based NGO against the National Tiger Conservation Authority (NTCA), which is responsible for monitoring all tiger reserves. At the heart of the matter lies the reluctance of a few states — Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, Bihar, Maharashtra and Madhya Pradesh — to delineate core and buffer areas within their tiger reserves, despite repeated directions from the court.

According to Ashish Kothari of Pune-based NGO Kalpavriksh, who has worked with a number of state governments, this reluctance stems from the fact that notifying core areas would restrict commercial and industrial activity such as mining (rampant around parks like Panna Tiger Reserve), hotels and the building of dams. Creating core and buffer areas is, however, what a map is to a long road-trip — just the first step, towards overhauling India’s management of wildlife areas, especially tourism around them. In its order the Supreme Court also brought up the Ministry of Environment and Forests’ (MoEF) ‘Guidelines for Ecotourism In and Around Protected Areas’, which are to be the basis of the ecotourism policies of individual states.

Not surprisingly the Court’s interim order has evoked a maelstrom of emotional rhetoric and vehement opinion from conservationists, park officers, resort owners, tourists (a number of whom have made bookings for the approaching wildlife season) and politicians. Anecdotes masquerading as fact and doomsday prognoses (“tigers will disappear if tourists are not around to keep a check on forest departments” and the like) are being bandied about.

The casualty, as always, has been the science of wildlife management, which needs to be the bedrock of this debate. Whether tourism should be allowed in the reserves, and to what extent, will follow from an overall assessment of the health of a reserve and the current impact of tourism on it. A few studies looking at the impact of tourism have been done, but they need to be expanded to all wildlife areas and all stakeholders in the debate need to be involved.

Corbett: A Case Study

One of the few studies of tourist establishments around the Corbett Tiger Reserve was done by the Institute of Hotel Management, New Delhi, for the Ministry of Tourism in 2011. It surveyed 77 existing resorts and the 17 that were at that point under construction. Six of these, the study found, were situated in a corridor used by the reserve’s wildlife. In an area where water is scarce in summer, 20 of them had swimming pools. Four had discotheques. Most of the resorts — 71.4 per cent — have come up in the last five years, the period during which the rush to cash in on Corbett’s tourism revenues has turned into a stampede. Taken together, these resorts had 1,421 rooms and 3,197 beds. Of the rooms 69 per cent were air-conditioned, powered largely by diesel generators. Less than 20 per cent of the resorts used any form of solar energy; only 37.6 per cent segregated waste; and just a tenth had eco-friendly buildings. The report goes on to note, in what now seems like cruel irony, that, “There are some camps e.g. Camp Forktail Creek in Bhakrakot etc which are operating with no or minimum damage to the environment and wildlife.”

Equally damning is ‘Management Effectiveness Evaluation (MEE) of Tiger Reserves in India’, a study done by the Wildlife Institute of India (WII) in conjunction with the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). WII relied on a set of experts to evaluate tiger reserves on an extensive set of criteria — ranging from how well-staffed a reserve is, to the involvement of local people and the facilities available to tourists. According to the study there is “little or no involvement of stakeholders in tourism revenue (community related as opposed to private enterprise)” in Corbett. It goes on to say that “too much time and manpower is involved in managing tourism and tourist facilities which takes away from the primary tasks of Tiger Reserve staff”. As a solution it advocates greater community participation.

Of Kanha and Bandhavgarh, the report states that the large number of visitors — over 100,000 annually — are increasingly straining resources; and in both parks a “ring of resorts is quickly closing dispersal routes for the tiger”.

Tourists and Tigers: The Big Picture

The most comprehensive set of studies on tourism in India’s protected areas has been done by Krithi Karanth, a scientist at Columbia University. In a set of three papers published over the past two years, she and her co-authors have looked not only at tourist resorts and facilities, but also at tourists’ own estimation and opinions of their experience, and the perception of local communities of tourism in the parks.

In their first study, published in 2010, they interviewed owners of 336 tourist facilities around 10 protected areas in India. They found that most (72 per cent) of the facilities were established post 2000, and that 85 per cent of the resorts were within 5km of the park boundaries. These resorts relied heavily on local resources like wood, which was purchased locally in over 93 per cent of them; and water, for which the dependence of bore wells ranged from 40 per cent in the Bhadra Tiger Reserve to 100 per cent in most other protected areas. Most of them employed local staff, but only in poorly paid menial positions. “What came as a surprise to me,” Karanth says, “were how few people tourism employed from around protected areas — less than 0.001 percent of the population living within 10km.”

In a later paper, ‘Wildlife Tourists in India’s Emerging Economy’, Karanth and her colleagues surveyed 436 visitors to Nagarhole, Kanha and Ranthambhore. In all these parks tourists “wanted park rules to be better enforced, limits on the number of vehicles and people allowed inside, and improved vehicle safety”. In Kanha the tourists objected to the playing of loud music and wanted ‘tiger shows’ — the crowding in of tigers by tourists on elephant back or jeeps — to stop.

But the bigger worry for people like Karanth is that, soon the communities that live around these forests, but which derive few benefits from them, are going to turn against the tourists and the parks. Already in parks like Nagarhole only 23 per cent of the local community said they’d be happy to have more tourists. In Kanha and Ranthambhore more than half the people surveyed had been in confrontation with park authorities.

This is in sharp contrast to what Karanth found in Nepal, where community involvement in park management and tourism in parks like Chitwan National Park is high. The majority of households near Kanha and Ranthambhore felt that “only outsiders benefit from tourism and that tourism was damaging their culture”. “We’re lucky that we have a culture that has a great tolerance for wildlife,” Karanth says, pointing out that the majority (over 68 per cent) of people around Kanha, Ranthambhore and Nagarhole still had positive attitudes towards the parks, “but it can’t go on like this.”

Solutions

From these studies, it is quite obvious that tourism is not as it should be in India’s parks. Whatever its outcome, the Supreme Court case has revitalised an urgent debate, highlighted the need for a radical rethink.

The MoEF’s ecotourism guidelines are a starting point. Their focus is on making the benefits of tourism more equitable and tourist infrastructure more ecologically friendly. They require each state to formulate its own Ecotourism Strategy (using the MoEF guidelines as a benchmark), as part of which all tourist facilities within five kilometres of the boundaries of a park will have to pay a minimum of 10 per cent of their turnover as a ‘local conservation fee’. Each protected area is to also constitute a Local Advisory Committee, which will include the local divisional commissioner, manager of the park, local tourism officer, scientists, members from the district panchayat and other stakeholders. This committee will implement the Ecotourism Strategy and monitor all tourism development that happens within five kilometres of the park.

They also stress the need to move tourism out of core areas or protected areas to the buffer zones. This process is likely to take time. In the interim the guidelines allow for using 20 per cent of the core area of parks that are larger than 500 sq km for community-based tourism, subject to the condition that 30 per cent of the buffer area be restored as a wildlife habitat within five years.

While these guidelines have evolved over the last two years, precedents do exist. Amendments in 2003 and 2006 to the Wildlife Act allowed for the creation of advisory committees/foundations similar in structure to those envisaged in the Ecotourism Guidelines, for wildlife sanctuaries and tiger reserves, respectively. The difference being that these had the broader task of creating overall management plans for their areas.

The former never took off. As for the latter, a few Tiger Foundations were set up. Some like the one set up in Corbett remain on paper, but those in Periyar and Bandipur have been somewhat successful in creating a management system for these parks. The Periyar Foundation, as it is called, has successfully established an ecotourism programme that involves local communities. Community-development initiatives have ensured that poaching and sandalwood smuggling have reduced. Bandipur’s Tiger Conservation Foundation has managed to reduce tourism impact on the reserve by bringing down the number of vehicles allowed into the buffer zone to 21 per day. In contrast, Corbett, which is a third larger than Bandipur, allows in more than 100 vehicles per day — even into the core zone.

Central to the working of these foundations and to the creation of a management system is the determination of the carrying capacity of a protected area, that is, the number of visitors and the kind of tourism that it can sustain. Here the MoEF ecotourism guidelines falter. They list a method based on road length within the park and the distance between vehicles that is “so simplistic as to be ridiculous,” according to Krithi Karanth. There is no single procedure for determining the carrying capacity of a park — for each the procedure varies depending on its geography, the species it harbours, the pressures it faces and its current state of conservation.

Once again we have some local precedents. A.K. Bhattacharya of the Indian Institute of Forest Management in Bhopal has created a matrix of indicators (ecological, infrastructural, social, economic and one based on visitor experience) that can be adapted for use in different parks. “We need to create comprehensive and adaptive management systems that are tailored to each protected area,” says Ashish Kothari. Both he and Karanth believe that there is no one-size-fits-all model for tourism in these areas. One of the biggest mistakes of the MoEF guidelines according to Kothari is the effort to impose such a model through rules such as those governing the use of core areas.

Some protected areas might need to be made entirely off-limits for long stretches of time, as in the case of the Nanda Devi National Park (except that the government never reopened the park). Others might be able to sustain high levels of tourism even in core areas. Creating these systems will require a lot more research, a honing of wildlife management techniques, but more significantly a fundamental change in mindset. “The talent for it exists,” says Karanth, “We just need to get it on board. Done right, tourism can be a big winner for conservation.”

Postscript

On August 22, under intense pressure from various lobbies, the MoEF did a volte-face in the Supreme Court, asking it for permission to review the very guidelines that it had submitted to the court recently. In its affidavit the ministry asked that it “be permitted to further review the guidelines and conduct more consultations with all stakeholders including state governments and representatives of local indigenous communities, besides reviewing the process adopted by states in notifying the buffer areas of tiger reserves.” All of this had purportedly already been done.

Asking the MoEF why it had recommended the phasing out of tourism from core areas in the first place, the Supreme Court extended the ban on tourism, scheduling the next hearing for August 29. The outcome of that hearing will not be available at the time of going to press. The battle for the jungle, however, looks set to continue.

Indian wildlife management policy

tourists and tigers

wildlife and tourism

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.