I cannot think of two other locations that are as terribly twinned by imperfectly forgotten textbooks and by

I cannot figure why people are drawn there — I ask a friend who’s been there, and she says, “Got dragged there, man. By family. Was something to tick off on a list.” After having been, I don’t know if this is the only thing that compels the French tourist who pauses between each cave to pull out some guide for a careful five minutes of preparation, or the Marwari paterfamilias in Ellora’s Cave 5 who stops yelling instructions to his tech-savvy son about what to photograph to ask me in wonder how many years all this — and here he whirled around on his heels — might have taken.

The man sharing transport with me to the airport in Mumbai notices me scribbling and eventually asks where I’m going. When I tell him, he has a question to offer. What can you say about a place that has been visited and written about so many times? I hold forth about hacking through my own ignorance and finding a new path to the waterfall till I notice the look on his face. At six in the am, I am a weapon of mass destruction.

When we get to Ellora, the photographer Dhiman and I are immediately accosted by a small crowd—some hold out glossy Aurangabad-Ajanta-Ellora pamphlets in different languages, one offers to guide us, and another simply holds out a pair of arms covered with beads and shiny necklaces. Dhiman has the right peremptory cackle and, as they evaporate, another man begins to keep pace with us. When we notice him, he holds out a nondescript rock which opens like an oyster a second later to reveal crystals of a dazzling purple. He has no spiel, just the single word “Ametheesht”. “Buy later,” he adds, before falling away.

As I follow the arrow to Cave 1, I wonder if I should have hired a guide. One sentence in the description outside reassures me; “austerely plain and consists of an astylar hall having eight cells and is devoid of sculptural representation”. This is confirmed when an official guide steams in, rattles off a sardine-tin of facts and jargon, and hurries his harried flock to the next cave. I climb into one of the cells and, when my eyes adjust to the dark, I see a ceiling covered with mould. When I look beyond, a faraway hillock materialises in elaborate detail and I am glad I chose such leisure.

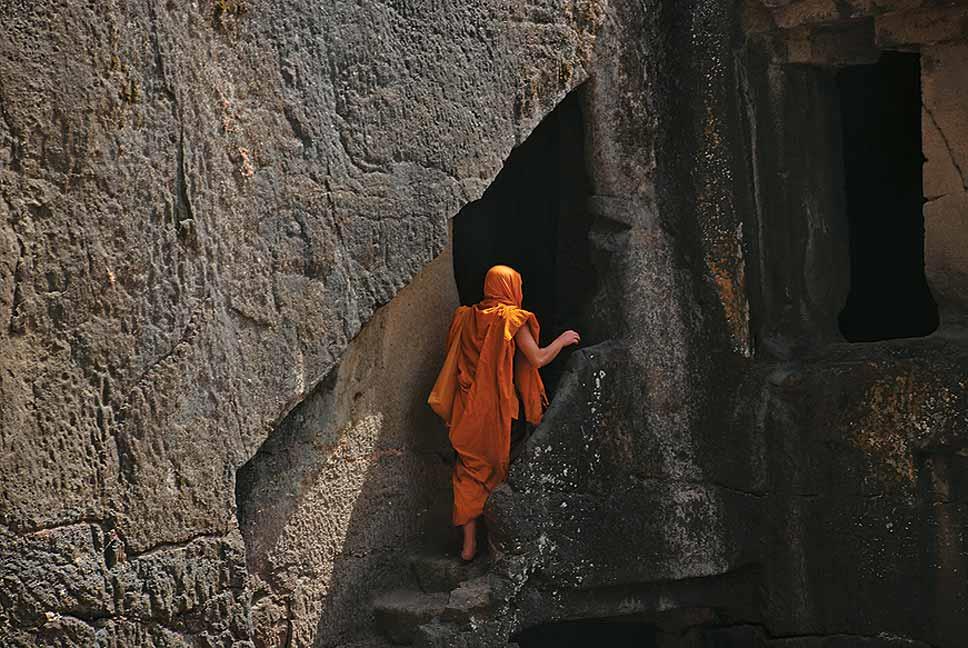

The Buddhist caves demand a rigour of the senses. The basalt is pocked by weathering and flecked green and orange and, in one cave, quartzy white bands run through the carvings like interference lines on a TV screen. Now and then a beheaded Buddha or an anonymous figure minus limbs turn up — victims of a vandalism so ancient it is now impossible to tell if it was caused by time or by human hand.

At the chaitya known today as Cave 10, I look up at the ribs of the ceiling and wonder about this need to mimic ordinary interiors. Dhiman reaches for his tripod and an attendant materialises immediately to say that written permission from Dilli is needed for that sort of work. I amble over to try and get to the bottom of this mystery and, when he turns to make conversation with me, Dhiman manages to fit camera to tripod and squeeze three shots of the vault into those few seconds. A little later, a holidaying family turns up and something about their jauntiness gets the old man’s goat. He pursues their progress with a beetling brow and rises when he sees the children climb onto a ledge to strike a pose. As we step out to explore the many floors of Do Tal and Teen Tal (caves 11 and 12), I hear him reach the climax of his lecture with the words sona hai yeh, golden hai hamara, golden.

The Kailasanatha is an ambush — we are unprepared for such scale and vitality. The architectural conceit that defines it—temple as holy mountain — beats its way to us through the milling, festive gawkers.

It is evening by the time we complete the Hindu and Jain caves. The Hindu caves convey both the energy of the Brahminical revival as well as something of the cockiness of the kings who had them built. The Jain caves are crowded into the remaining bits of hillside and achieve a more intimate encounter with the objects of veneration, while retaining the vigour of the Hindu caves. I am, nevertheless, haunted by the brooding, restrained grandeur of the chaityas and the viharas from the Buddhist section over the rest of the day.

I can’t help returning to my questions. Are the many who visit drawn by a notion of local, available history? What aspect of the holy do these caves retain? What triggers the prohibitions and the reverence that marks faith? At Kailasanatha, there are signs pleading with visitors to desist from climbing onto statuary, and a guard is posted there to prevent such an eventuality. At the Indrasabha (Cave 32), I notice two men with handkerchiefs over their heads prostrating before the primary Jain figures — Dhiman achieves some coordination with them when he hits the floor to catch the ceiling in the dying evening light.

The landscape changes dramatically after we cross Ajanta village—the road corkscrews down a hillside after a two-hour drive past green fields. The first thing I notice on our descent is a space-age structure—revealed to be an amenities centre, still in construction, financed by the Japanese government. Unlike Ellora, which remained in public view due to its proximity to the ancient trade routes, Ajanta managed to disappear in the centuries after Buddhism waned, till its rediscovery in 1819 by John Smith, a British officer, whose sharp eyes spotted what is today Cave 10 while out on a tiger-hunt.

Ajanta seems more ‘organised’. We have to pass through a shopping plaza and run quite a gauntlet of importuning before we find the pick-up point for the bus to the caves. I also seem to recall a series of tickets—including one called a ‘light-ticket’. This fee finances the costs of illumining the caves with soft electric lighting. The walkway is crowded with notices advising tourists about ‘biting honeybees’, the danger of rock-falls and the charges for being hoisted up to the caves by chair.

While the paintings suffered some damage over the centuries due to natural causes, such as forest fires and water draining into the caves, they seem to have suffered far greater damage after their rediscovery—read early attempts at cleaning and preservation and the pressures of tourism. Of the 29 caves, only about six continue to hold substantial remnants of the original paintings. In one cave, the paintings are protected by glass. There are strict rules in force about flash photography and the number of people allowed into a cave, but all this may only postpone the inevitable.

The walls of the caves bear paintings focused on narrative, while the ceilings are occupied by Buddhist motifs. The narratives—sourced from the Jatakas—seem to have served as objects of contemplation for novices, while also underscoring a compact of power between royal donors and clergy. The paintings are obdurate when subjected to speed-viewing and demand of the eye an unlearning of the normal notions of sequence. I notice the Padmapani and miss the Vajrapani (in Cave 1), and somebody has to point out the apsara from Cave 17. I make no mistake with the Mahaparinirvana in Cave 26—the Buddha’s departure from the world — but that isn’t one of the paintings.

My primary memory of Ajanta does not come from the supple bodies or the definite hues that crowd the paintings, nor from the graceful chaitya-window or the stark Hinayana stupa of Cave 10, nor from the Mahaparinirvana. It is the unfinished caves that register most strongly. At one cave, a half-finished Buddha emerges top-first from the basalt. The incomplete Cave 4 has a ceiling which records the swirling lava-flows from an even more distant past. I pick my way through the uneven floor in the abandoned shambles that is Cave 24. It is these images that fill my dreams for days afterwards.

There is a reliable way of doing a classic destination: to arrive and to have it explained to you, or to read up about it and have all of that confirmed by arrival. There is nevertheless something to be said for cutting oneself free and lurching about in an aleatory drift. To do that is to reach the limits of comprehension quickly, to be dwarfed by place, to be freed from the bookish certainties of the present, to arrive at the right size in which one may truly encounter the destination, in the lore of the ordinary people who live thereabouts.

At the caves, this encounter begins auspiciously — in the pervasive, half-herbal odour of bat-shit and the museum-fustian dialect in which the Archaeological Society of India chooses to speak. After being dizzied by words like ‘apsidal’ and ‘hypostylar’, it was a relief to run into Vishal who flashed an ASI badge at us and offered to carry our effects and look after our footwear. He wouldn’t enter the caves with us — that was for the official guides — but plied us with stories as we walked from cave to cave. About Arnold Schwarzenegger arriving in Ajanta and leaving in a huff because “the white ladies kept trying to kiss him”, while the Indians behaved themselves; about a sher, which kills a langur now and then; about how the ASI has planted squares of glass in one of the cave-ceilings to provide early warning of a collapse; about how the caves were all dug out of a rock called baltaas and about how it was okay for women from the time of the paintings to drink. He tells me that his father used to carry tourists up in a chair till recently and that he himself began helping tourists to support the family. I ask if he wants to become a guide — that means doing an MA in History and spending much money in bribes. Ellora isn’t as impressive as Ajanta; too many indecent couples. He tells me that the helpers were once a larger group; the numbers have shrunk because several of his friends married foreign tourists who fell in love with them. They preside over restaurants abroad and visit occasionally. Vishal tells me he can now speak some Japanese and Korean, and smiles hopefully.

Sultan sidled up to me at the Observation Point while Dhiman attempted a shot of the scarp which contains the Ajanta caves and began a conversation. He pointed out Lenapur, the village closest to the caves and said that the name comes from the Marathi ‘leni’ for caves. He called the government thurredclass for having gone to sleep after promising to acquire his fields to develop the Observation Point. Sultan told me the John Smith story in great detail and said that the tiger-hunting story was all bunkum. Smith had come to spend time with his local girlfriend Paro. A moment later, the already athletic Paro was declared the girlfriend of Robert Gill, the painter who made copies of the pictures in the caves. Paro’s tomb, in Ajanta village, was now being refurbished with Japanese money. He returned to etymology at this point and told me that Ellora takes its name from ‘verul’, the Marathi word for a termite-nest, and not from Elapur, its old name. Ajanta, he said, sounding the hard Marathi ta, means ‘a settlement of people’ but nowadays it is A-janta, not for the people, only for tourists. Gill came to this part of the world looking for precious stones, which he could powder and use in painting. Sultan had amethysts and mountain coral to sell. Would I please look? Littal you business me anna, he said, triumphing in one fluid move over the problems of syntax and history that separate us, beating his insidious way into my heart, affirming our shared citizenship in the republic of narrative-whores.

The Information

Getting there

Aurangabad (27km from Ellora, 107km from Ajanta) is well connected (flights from Mumbai start from Rs 2,700, Delhi Rs 4,100). The city is fairly well connected by rail too (Delhi Rs 1,532 on 2A; Mumbai Rs 574).

Where to stay

In Aurangabad, try the mid-range Lemon Tree Hotel (from Rs 2,700 for a single; 0240-6603030; lemontreehotels.com). Or try the Ambassador Ajanta (Rs 4,000; 2485211;ambassadorindia.com) or the Welcomhotel Rama International (Rs 3,000; 6634141,welcomhotelrama.com). Easier on the wallet are Maharashtra Tourism Development Corporation’s Holiday Resort (Rs 936; 2331513) and Amarpreet (Rs 1,800;

6621133).

Aurangabad

Buddhist caves

cave paintings