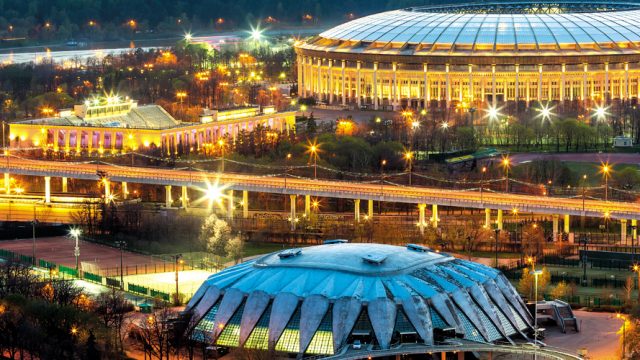

I have been going to Moscow regularly for nearly 30 years, and with each return the city’s skyline seems to have mutated and rejuvenated itself, at a speed that accelerates more and more with each passing season. This year, I was reminded of Oscar Wilde’s novel, The Picture of Dorian Grey, whose hero (or anti-hero) is a man of extraordinary beauty who never ages. A painted portrait of him ages instead, becoming more and more disfigured and wizened as the years go by. Dorian’s sins become etched on the canvas and on his soul, but his face remains smooth and youthful. Moscow now feels like my own Picture of Dorian Grey, in reverse. The cleaner, hipper, more modern, vibrant and debauched the city becomes, the older I look and feel, together with the city’s 12 million inhabitants who, in a country with one of the lowest birth rates in the world, are all, literally, getting older. The demographic challenge facing Russia is of no concern to Moscow, however. Bright modern buildings have risen where grey Soviet monoliths fell, and once derelict townhouses and palaces have regained their former glory. Moscow is, and always has been, the pulsating heart of Mother Russia, regulating the flow of business, money, avant-garde new art trends, and the eternally expanding and contracting fist of power emanating from the heart of hearts, the Kremlin and Red Square. The more corrupt and psychotic this power becomes, the more Moscow seems to blossom in its newfound beauty. The Red Square may be famous for its Kremlin and the psychedelic domes of St Basil’s Cathedral, built in the mid-16th century under Ivan the Terrible, but another significant attraction today is the GUM (Glavniy Universalny Magazin or Main Universal Shop) shopping mall. In the Soviet era, GUM, originally constructed as a large trading area in the late 19th century, housed a few dreary shops displaying the formless nylon dresses of the good communist housewife and factory worker. Today, this massive steel, stone and glass-roofed building is a glamorous, brightly-lit shopping arcade, where Chanel, Dior and Cartier rub shoulders with home-grown luxury shops. The most visible of these is Bosco di Ciliegi and Bosco Sports, shareholder of GUM and official sportswear designer for the Russian Olympic Team. During my last visit in February 2014, the exquisitely designed shops were overflowing with Sochi 2014 Winter Olympics merchandise, all beautifully made, ultra fashionable, and exorbitantly expensive. Expensive is perhaps the word that most frequently comes to the mind of the traveller visiting Moscow. In 2013, the city was ranked as the second most expensive in the world for expats, in a survey by the global relocation and health consultancy firm Mercer. Even though tourists rarely face the same daily expenses as expats, accommodation digs a hole in most tourists’ budgets. The majority of hotels in central Moscow are geared towards a well-oiled (literally) business clientele, and prices can double or triple overnight if a conference or big event is taking place. If you can afford one, however, the level of luxury and service in central Moscow’s opulent hotels is in league with top hotels anywhere in the world. Top of the list would have to be the National Hotel, built over 100 years ago across from the Kremlin and Red Square, and one of the few places of pseudo luxury one could find in the Soviet era. Today, it has been renovated but continues to ooze nostalgia and charm. For a bit of new Russian bling, walk round the corner to the Ritz, about 200 metres up Tverskaya Street, the large avenue that leads in a more or less straight line from the suburbs all the way to the Kremlin (albeit with a few name changes on the way). In 2007, this five star hotel opened its doors on the site of one of the only business standard hotels of the Soviet era, the drab and infamous Hotel Intourist. Intourist was completely demolishedto make way for a rather garish replica of a 19th century palace, which will delight aficionados of gold-coloured paint and heavy marble columns. The 19th century surrenders, however, to the 21st century in the twelfth floor glass-roofed O2 lounge. Here one can sip expensive cocktails and nibble on sushi while gazing at the red stars of the Kremlin and the golden domes of the three cathedrals within the Kremlin walls. For those for whom sightseeing involves more than taking in panoramic views from rooftop bars, there is the issue of transport to consider. Moscow taxis are expensive, and hotel car services can charge the price of a flight from Delhi to Goa for a few hours sitting stuck in a traffic jam. A far better option is the metro, a Soviet-era institution that still retains much of its past glory. Built mainly in the 1930s, the metro was one of Stalin’s pet projects, and he wanted it to be a palace that workers could call their own as they travelled to work. To this day, 21,000 square meters of marble cover the walls of the original metro stations, and lighting is provided by elaborate chandeliers hanging from high, ornate ceilings. The metro has become a tourist attraction in itself and travel agents conduct special tours of its most celebrated stations. But the Moscow metro is neither for the claustrophobic nor the unfit. Past the entrance and the ticket gates, seemingly never-ending escalators thunder down into the bowels of the earth, hauling passengers to platforms and trains that run along one of the deepest metro systems in the world. Miles of labyrinthine underground passageways lead from platform to platform, up and down stairs and across tunnel-bridges where most signs are onlyin the Russian Cyrillic script. In winter it is hot, and passengers in fur coats and heavy hats itch and sweat as they trudge along, hurriedly, from one train to the next. In summer, they just sweat. Upon finally reaching street level, it is prudent to factor in a good 15 to 20 minute walk before reaching one’s final destination, as metro stations are far apart from one another. Travellers are advised to wear comfortable shoes, and layers that can be easily removed and put back on, especially in winter. This can prevent, to an extent, the post-metro frozen sweat that crystallises on overheated bodies as soon as they hit the cold outside. In spite of all this, a trip down the metro is well worth the effort, as the grandeur of this unique public transport system never fails to amaze. Today, Putin’s capitalist Moscow reaches as high into the sky as Stalin’s communist Moscow dug deep into the ground (although Stalin did initiate his fair share of skyscrapers as well). So if underground tunnels are not your cup of tea, a shot of vodka and some nouvelle cuisine in one of the city’s new sky-high restaurants may be more appropriate, expense notwithstanding of course. In the last decade, dozens of skyscrapers have shot up all over Moscow, like wildflower in a desert after a sudden rain. The rain in this case is called oil. Many of these new skyscrapers now host fashionable restaurants on their top floors, where accomplished chefs and baristas compete for an ever more demanding, eclectic and wealthy clientele. The highest of these, Restaurant Sixty, is on the 61st floor of the Federation Tower of the Moscow International Business Center, in Moscow’s Western Presnensky district. At night the glass walls open outwards and diners can view, unobstructed, the other skyscrapers of the new Moscow, their shiny smooth surfaces as slick as the fuselage of large aeroplanes. Further towards the city centre, the White Rabbit restaurant, on the 16th floor of No.3, Smolenskaya Square, looks out onto the golden onion domes of the mainly new Christian Orthodox churches that emerge here and there amidst twentieth century Stalin-era towers. Many of these churches have been built or rebuilt in the last 15 years: indeed, once known as the city of forty times forty churches, Moscow lost most of them to the anti-ecclesiastical fervour of the Bolshevik revolution, which saw the destruction of places of religious worship as the ultimate victory over a past governed by superstition and slavery. Since the fall of the USSR in 1991, rebuilding churches has been one way for the new Russia to reclaim some of its pre-revolutionary identity. The most controversial of these new-old churches is probably the cathedral of Christ the Saviour, built originally in the second half of the 19th century, finally consecrated in 1883, and blown up under Stalin’s orders in 1931. He had planned to build what would have been the tallest building in the world in its place, the Palace of the Soviets, but the project never got off the ground due to a mix of war, over-ambitious planning, and lack of funds. Instead, the site was turned into the largest open-air swimming pool in the world. Open all year round, a cloud of vapour hid swimmers from each other during the cold winter months, making it the perfect dating and mating venue for lovers. The pool was closed down in 1994 and the cathedral rebuilt between the mid-1990s and 2000 on the basis of the original 19th century plans. Its silhouette now recreates the Moscow skyline of the early 20th century, but die-hard historians and orthodox believers bemoan the modern touches inside the cathedral as well as the haste with which it was rebuilt. Bronze instead of the original marble was used for the bas reliefs; bright, almost garish colours adorn the inside walls; and worst of all, it is rumoured that fast-working Muslim Turks undertook much of the heavy construction work. If this were not enough controversy, the cathedral altar is where the now world-famous punk band Pussy Riot gave the February 2012 performance that landed two of its members in jail for nearly two years. Whatever one may think of the Cathedral of Christ the Saviour, it is one of the largest and brightest landmarks that testify to Moscow’s permanent impermanence, in which change is as likely to revive the past as it is to usher in the future. Someone asked me recently whether thugs still roam the streets of Moscow. I suppose that depends on your definition of a thug. Today, most thugs are to be seen in the black Mercedes cruising along the city’s wide avenues, more often than not flashing a blue light that may or may not have been bought off some corrupt official. The streets of central Moscow, however, remain relatively safe, even at night, unless of course your skin is a shade too dark for the average Slavic born-again nationalist. Racially motivated attacks remain rare, but they do occur, and according to the UK Foreign Office travel advice website, particularly around 20 April, the anniversary of Adolf Hitler’s birthday. If all this has not put you off, the best time to visit Moscow is in mid-winter or mid-summer. If you are lucky, a winter visit will conjure up ice blue skies that melt into a fluorescent glow at sunset and sunrise, and crisp white snow sprinkled like icing sugar on the fairy tale buildings of the city centre. Summer can be equally magical as the days stretch far into the night and the streets come alive with Muscovites soaking up the few short weeks of sunshine before returning to their long winter hibernation. But weather, as everything else in Moscow, is forever changing. So come prepared, expect the worst and you may be in for a pleasant surprise. The information Getting there Visa Currency Where to stay What to see & do

Aeroflot and some Middle Eastern airlines fly to Moscow from Delhi for about Rs 40,000 (round trip, economy class). European carriers like KLM and Air France cost more (about Rs 55,000).

Visitors have to submit documents for visas in person (011- 26873799, [email protected]; visa.kdmid.ru). Applicants from Maharashtra, Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Daman & Diu and Goa have to apply to the Consulate General in Mumbai (022-23633627/28). Tourist visas are issued for 30 days (Rs 3,290).

1 Russian rouble (R) = Rs 1.75

Moscow hotels, as we said, don’t come cheap. The opulent and historic National Hotel(from Rs 14,000; national.ru) delivers modcons with bucketloads of nostalgia. Just across from Kremlin and Red Square, it triumphs with its location as well. Turn a corner and there’s The Ritz-Carlton(from Rs 23,500; ritzcarlton.com), a fine establishment of stylish rooms, enormous en suite bathrooms and exceptional service, with the Red Square less than a minute’s stroll. Hotel Arbat(from Rs 10,000; president-hotel.ru) would be your more white-collar, serviceable option, quietly located a metro station away from the Red Square. For Moscow-on-a-budget as only Moscow can be, consider the monstrously huge and futuristically constructed Hotel Cosmos (from Rs 4,200; hotelcosmos.ru/eng), which looms a half hour away from the city centre near the Space Museum (the same theme).

You will enjoy the deeply underground Soviet-era metro, the high-rise bars with gorgeous views, the restaurants offering nouvelle cuisine, and strolls by the historic centre. There’s also the statuesque Cathedral of Christ the Saviour, which stands opposite another landmark now famous for its present-day metamorphosis: the Red October Factory, renowned for its delicious chocolates since before the 1917 revolution. The red brick factory building is still standing, but the chocolate production itself has moved to Moscow’s outskirts. Art galleries and restaurants have now claimed the old offices and workshop floors. Visit the Red October site after midday as most places are closed before then. Try out a traditional Russian pancake at No Crepe, or sip a hot coffee while browsing through books on cinema or photography at the Lumiere Brothers Photography Centre. The more design-oriented may want to check out the Strelka Bar, where profits go toward funding the adjacent Strelka Institute, whose mission is to bring new thinking on urban design to Moscow. In 2013, it was nominated one of the best architecture and design schools in Europe by the Italian Architecture and Art magazine.

Red Square

Russia

St Basils Cathedral

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.