The most difficult decision I had to make while packing for a weekend in Old Delhi, was what sort of attitude I ought to carry with me to this contiguous yet discrete part of the capital city. Many travellers have written about how home can only be understood once one leaves it for the world; and how the world becomes known to us through what we find familiar in it. But who would advise me about ‘travelling’ to a part of the city that I had been flitting in and out of for years? New Dilliwalas have a complex relationship with Shahjahanabad, which is not just the historic capital of the Mughal emperor for which it was named, but also the last of Delhi’s great citadels; and it has been almost continuously ruined and rebuilt since it was founded in the mid-17th century. We read books about it, raid its kuchas and its katras for perfumes and precious metals, write blogs about it, fill city magazines with descriptions of its flavours and scents. Us new Dilliwalas bemoan the loss of puraani Dilli’s history because it is also our history. But the volume of trade that pumps life into the rattling, breathing sheher is mostly irrelevant to us; we don’t really live there. Two nights of sleeping in the old city would at least be a different kind of adventure, and the Hotel Tara Palace seemed a promising start. The budget hotel with an incredible view is tucked away on an offshoot of Esplanade Road, the wide thoroughfare created by the British after 1857 to separate the city from their military encampment at the Red Fort — Archaeological Survey of Indiaa sliver of which was visible from the balcony of my alley-facing room. Tara Palace rises above the other buildings in the cycle market around it, and the hotel, with its rooftop view of the Red Fort, the Jain Lal Mandir, the Gauri Shankar Mandir, the Gurudwara Sisganj, and the Jama Masjid, has apparently been used for several film shoots, including Chandni Chowk To China (the lane outside was turned into a facsimile.of Parathewali Gali), Black & White and Delhi-6. Rather than zooming in on the landmarks though, the fun of actually staying in the old city was the freedom to keep glimpsing these monuments in my peripheral vision. So, just on the way to purchase a replacement for a forgotten toothbrush, I stopped by the Old Famous Jalebiwala for a sugar rush before ducking into Dharampura, the area east of Esplanade Road and south of Chandni Chowk. The historic dharamsalas in this Jain-dominated area are a bit difficult to find, not least because there are nearly a dozen of them scattered about, but worth a visit for their colourful wall paintings, intricate marble interiors and golden daises crowded with wide-eyed tirthankaras. The prominent Naya Mandir, built in 1807 is generally open in the mornings, but the smaller Panchayati Mandir, originally built in 1745, is a peaceful stop in the evenings. Emerging out of the tinsel-strewn Kinari Bazaar and bypassing the greasy plates in Parathewali Gali, I loitered at the Northbrook Fountain intersection, also called Bhai Mati Das Chowk after a disciple of Guru Tegh Bahadur; their martyrdom at this spot is gruesomely reconstructed next-door at the Bhai Mati Das, Sati Das Sikh museum and commemorated by the Gurdwara Sisganj. Besides me, the only other people not in a rush to eat, pray and shove were a couple of boys on the terrace of the 18th-century Sunehri Masjid opposite me, watching the occasional Mercedes barrel out of the gurdwara gates and scatter the stream of human traffic before getting mired in a glut of electric- and cycle-rickshaws. Above the greenish bronze domes of the masjid and the gleaming golden domes of the gurdwara, a full moon rose into the sky, its light opalescent behind the hazy veil of summer pollution. The heat was oppressive. I was tempted to head down the ‘moonlit avenue’, luminous with sequined garments and neon signage, for a nimbu-soda banta from its supposed inventor, Pandit Ved Prakash Lemonwale. Instead, I headed back to Tara Palace for a stiffer drink. A few friends joined me on the roof, where the staff accommodatingly laid out a plastic table and brought us strong beer and vegetarian snacks. Eventually, the Jama Masjid, twinkling with tastefully restrained fairy lighting for Ramzan, beckoned, and we headed towards it for some proper grub. We ascended above the snacking and socialising crowd in bazaar Matia Mahal to the top-floor of Al-Jawahar Hotel, to dine on kebabs and kormas in its peach-and-saffron painted family room. Outside, the sweetshops selling multi-coloured blocks of halwa, vats of shahi tukda, matkas of phirni, and piles and piles of fried pheni and khajla, did brisk business. Back on Esplanade Road, labourers were unloading a couple of trucks, or stretched out across their handbarrows, taking a load off themselves. I was struck by how quickly the hotel’s alley had become familiar — probably because there was a bed waiting for me at the end of it. For a few minutes, I stood on my balcony, looking over a patchwork of roofs, unable to imagine them as once-spacious courtyards. The earliest account of a past I could think of that resonated with the present moment was just seventy-five years old: Ahmed Ali’s Twilight in Delhi. “But the city lies indifferent or asleep, breathing heavily under a hot and dusty sky,” Ali wrote, himself describing a time eighty years before his own. “Hardly anyone stops the flower vendor to buy jasmines or opens a door to satisfy the beggar. The nymphs have all gone to sleep, and the lovers have departed.” I was pleasantly surprised by my first organised rickshaw tour of the old city the next morning; the three hours with When in India, a tour company founded by sisters whose grandparents lived in a haveli, passed by quite fast. The sites covered — mostly masjids and markets — were not off the beaten track, but a steady narration of anecdotes and an album of historical photos kept things interesting. An early stop was the Khazanchi, or the treasurer’s haveli, one of several mansions that have fallen into ruin relatively recently. The sky-blue walls of the junk-cluttered courtyard set the tone for the rest of the morning. The sun dappled toppled pillars, dilapidated arches, and a door to nowhere — as well as the rough additions, bricked up windows and scattered furniture of the people living here. I was reminded of a letter Ghalib wrote around 1859. “If you want to know how things are in Dilli, read this,” he said, quoting his own verse: What was in my dwelling that your devastation could destroy it? What I used to have is here yet — just the yearning to construct. “What does this place have now for anyone to plunder?” he added. The poet’s question echoed as we trundled past the landmarks of Chandni Chowk: the E.S. Pyarelal Building, which once housed the Fort View Hotel; the SBI building in front of Begum Samru’s palace; the Central Baptist Church; the Allahabad Bank building; Mahavir Jain Bhavan; the erstwhile Town Hall, which began life as a cultural hub and may soon become one again; and the sprawling, still majestic haveli of Lala Chunnamal. Even if you don’t take a guided tour, a cycle rickshaw is the best way to admire the avenue’s last bits of marble latticework and wrought iron, hanging, like tattered lace curtains, between the shuttered shops on the street level and the concrete additions on top. Standing on the cupola-corned roof of Gadodia Market, a partially enclosed quadrangle in the Khari Baoli spice bazaar, I shielded my eyes against the intense glare. Below me the tingling heat of a million red chillies wafted from gunny sacks, above was a searing, cloudless sky. I noted the crowded Coronation Building, on the site of the notorious Namak Haram haveli, and on the other side of the Fatehpuri Masjid, the towering Crown Hotel — a hippie trail landmark famous for its rooftop parties in the early seventies, that now looks quite tame. Winding through Lal Kuan and Bazaar Sitaram, the tour ended at the company’s own simple haveli, which was built in the 1860s. Old museum photographs lined the walls, and there was a spread of bedmi-aloo, samosas, jalebis, tea and coffee and, best of all, a creamy kulfi from the local sweet-spot, Kuremal Mohan Lal Kulfi Wale. I got dropped off at Ajmeri Gate, opposite the Anglo-Arabic Girls’ School, but it was too hot to hop across to the 17th-century mosque within its premises. Men lay draped across their rickshaws, spread-eagled on any patch of dirt or pavement; I considered investigating the ‘Purdah Bagh’ to the north of Daryaganj, but decided instead to check in to Casa Homestay to recuperate. Quiet, residential Daryaganj, which was set with riverfront mansions when the Yamuna still ran along it, is an ideal base for exploration. A little before sunset, I walked to Delite Cinema, a sixty year-old hall that used to also stage plays, including by Prithvi Theatres, in its heyday. It was divided into two refurbished auditoriums, Delite and Delite Diamond — complete with cushy loos, hand- painted domed ceilings, and Czech chandeliers — several years ago. I watched half of Dawn of Planet of the Apes (Hindi) and half of Humpty Sharma Ki Dulhania, with the theatre’s obligatory ‘maha samosa’ in hand (they also sell chuski at the concession stand). More grown-up delights were in order afterwards at Thugs, the pub in the boutique Hotel Broadway down the street. The Mogambo Margarita was sadly unavailable (a broken blender), but a solid Kaalia (rum and cola), complete with paper umbrella, made up for it. Then to Moti Mahal, the decades-old restaurant that claims to have brought butter chicken to India during Partition (let’s leave aside the hotly contested debates of authenticity around this establishment). Dinner was tasty, and imbued with the sort of pleasant bathos that seasons all such exercises in consuming nostalgia. The small musical troupe churned out a timid rendition of ‘Kajra Mohabbatwalla’, the chicken was swimming in buttered tomato pulp, the breads were large, the spiced onions plentiful — all was well with the world and my air-conditioned bedroom was just five minutes away. The next day the city itself seemed to have been skewered and slapped into a blazing tandoor, but I forced myself to walk out into the Sunday book bazaar that lines the main arteries of Netaji Subhash Marg and Asaf Ali Road. Between biology study guides and sex manuals from the 1980s, I picked up a couple of books of poetry, before crossing back towards the quieter area around Ansari Road, Delhi’s traditional publishing hub. I paused at Jain Saheb’s (one of a couple of popular bedmi-puri breakfast joints in the area), which is renowned for its pumpkin sabzi, before trudging along the city wall — rebuilt here by the British — towards the Zinat-al-Masaajid, or ‘ornament of mosques’. Also called the Ghata Masjid, the mosque was built in 1707 by Zinat-un-nissa, one of Aurangzeb’s daughters. Zinat-un-nissa was a poet and a spinster (the mosque’s third name is ‘Kumari Masjid’, it was supposed to have been built with her dowry). Poets, including Mir Taqi Mir, apparently met here in the early 18th century; and one can imagine it must have been a pleasant spot at the time — a gilded building overlooking a river. Today, the mosque is spartan but pretty, with three striking black-and-white domes and pinstriped minarets that seem, in proportion, to soar upwards. Zinat-un-nissa’s tomb was removed by the British after 1857, but its Persian epitaph, composed by the pious princess, read: “It is enough if the shadow of the cloud of mercy covers my tomb.” Indeed, clouds were now amassing above the old riverbed, and the sky had darkened with the promise of rain. A strong wind blew across Delhi, heaving through the trees and taking with it my daydreams of this other city. Fat drops began to splatter the cracked sandstone around me. The minarets seemed to pierce the sky. The information Getting there Where to stay Getting around What to see & do Eat, drink & shop Fancier than the stores around it in Khari Baoli, Mehar Chand & Sons (facebook.com/mcs1917) sells well-presented blended powder masalas (from about Rs 200), special teas and spices. Harnarain Gokalchand (facebook. com/harnarains) has its local brand of khus, kewda, rose and other sharbats further down the street. Gulab Singh Johrimal on Chandni Chowk (gulabsinghjohrimal.com) is a charming old attar and incense shop (from Rs 12 for 2.5ml vial) with retro-packaging and old-fashioned cabinetry. In Daryaganj, Aap Ki Pasand (aapkipasandtea.com) is an oasis-like tea shop. Top tip

Old Delhi is 22km from Indira Gandhi International Airport, and about 4.2km from the New Delhi Railway Station. The Old Delhi Railway Station is next door. A taxi from the airport costs about Rs 375.

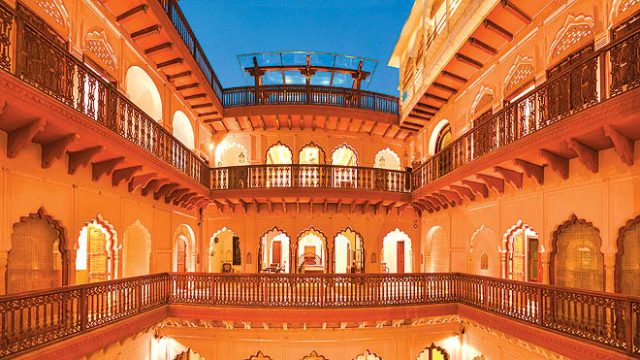

Hotel Tara Palace (from Rs 1,800 plus taxes, includes breakfast and airport pick-up; tarapalacedelhi.com) is a welcoming, spic-and-span hotel with all the amenities, plus a 24-hour restaurant. Another great place to stay is the Casa Homestay (from Rs 3,000, including taxes and a hearty, homemade breakfast; casahomestay.com) is a posh yet warm suite in a historic Daryaganj mansion. It is run by Colonel Abhimanyu and Reva Nayar, who live downstairs and provide all the amenities with a personal touch.

The Chawri Bazaar and Chandni Chowk metro stations are practical links to other parts of Delhi. Cycle rickshaws are the best way to get around (anywhere from Rs 20 to Rs 100 per trip; more for a tour). Several companies provide walking and rickshaw tours; When in India (wheninindia.com, from $50) tours are professional and comfortable, with branded rickshaws, uniformed drivers (some of whom speak English), cold drinks in chillers under the seats, and unobtrusive wireless headsets through which the guide gives information to the group. They average 1.5-3 hours and can be tailored for groups or individuals.

Red Fort, the Jain temples in Dharampura, Jama Masjid, Fatehpuri Masjid, Khari Baoli, Delite Cinema, Zinat-al-Masajid, Daryaganj book bazaar on Sunday and the local mansions

Old Famous Jalebiwala serves overpriced (Rs 50 per plate), oversized jalebis at the entrance to Dariba Kalan. Al-Jawahar hotel (about Rs 500 for two) is an airier alternative to the more-famous Karim’s next-door and worth a stop for the nihari at breakfast; likewise Moti Mahal (about Rs 900 for two) for butter chicken and ghazals at dinner; and Thugs (hotelbroadwaydelhi.com; cocktails from Rs 175) for drinks.

The Archaeological Survey of India’s free monuments app isn’t completely comprehensive, but it maps the major attractions. Download ASI Delhi Circle from the Google Play store. INTACH’s Delhi: 20 Heritage Walks (intachdelhichapter.org) includes two very informative booklets on the built heritage of North Shajahanabad and South Shahjahanabad.

Jama Masjid

long weekend

Old Delhi