On my evening safari into the Panna National Park, my

The tiger remains elusive, as is the nature of the beast. And we drive on and on, following the abundant pugmarks, the helpful tips from the patrolling park officials, and our own guide’s nose. To a man, the locals are determined to show us a tiger today. It is Panna’s reputation at stake.

As the light begins to fade, there is a rustling in the dry leaves ahead of us and we collectively hold our breath. A leopard crosses our path and, in a flash, disappears into the brown slopes. It’s my first leopard spotting, so I am still holding my breath (all those years of yogic breathing paying off). Our farmhouse family is still unimpressed. Said three-year-old has fallen asleep, empty Kurkure packet crinkling in his tiny hands, lips curved in a dreamy smile.

“Show me the tiger,” is a common — sometimes desperate, often demanding — refrain in our national parks but it feels particularly poignant here, given Panna’s history. In 1994, when Panna was brought under Project Tiger, making it India’s 22nd tiger reserve, the count was a healthy 23. Just 15 years later, in 2009, the tiger population was zero. Rampant poaching, poisoning by locals, and natural causes, all abetted by governmental indifference, had killed off the entire lot.

This is a sad story, but not particularly surprising, given how we have been failing our tigers consistently across the country. The twist in this tail, if you will, comes from how quickly and efficiently the park authorities responded to this situation.

It started with the entry of R Sreenivasa Murthy as the Field Director of Panna Tiger Reserve. Murthy was a man on a mission, as he got together a team as passionate about the cause as he was. In late 2009, they introduced two tigresses and one tiger into Panna from the other Madhya Pradesh reserves, and monitored their progress with great care.

Murthy remembers how tough the initials days were, given that tigers are creatures of habit and tend to seek out familiar territory. Surely enough, the male wandered off on his own, soon after being introduced into the Panna Reserve. He was headed towards home territory and had to be tracked for over 50 days before he could be tranquilised and brought back.

A couple of years later, in November 2011, the team added to the mix two orphaned tiger cubs from the Kanha National Park, which they had earlier rescued and raised for 18 months. This experiment in ‘rewilding’, another first in wildlife conservation in India — and the first such successful project in the world — has also paid off. And earlier this year, tigress T6 has been brought in from Pench, purely to correct the skewed gender ratio within the Park.

Today, 21 tigers roam inside Panna National Park.

I spot one of them during my morning drive into the forest the next day. She is introduced to me — from a safe distance — as T2. But more on her later. Unlike, say, Ranthambhore, the big cats here don’t have cutesy names, but are known by their lineage: the T series and the P series, to signify the tigers that were brought into Panna and those that were born here. Tiger spotting is increasingly common here now, and tourists are slowly making their way here, away from Bandhavgarh and Kanha, which lie deeper in the heart of the state.

But it is not as if anyone believed tigers would be back in Panna. Travellers who found their way to this part of the country came only for Khajuraho, our original Sex and the City town. Even at Taj Pashangarh, where I am staying, the tiger motif is glaringly missing. Instead, on the floor mats and door handles there is the ghariyal, the water crocodile found in the Ken river that flows through this region and inside the national park. “We couldn’t even have photographs of tigers here in the lodge when there were no tigers in the park,” says Narayana, the senior naturalist.

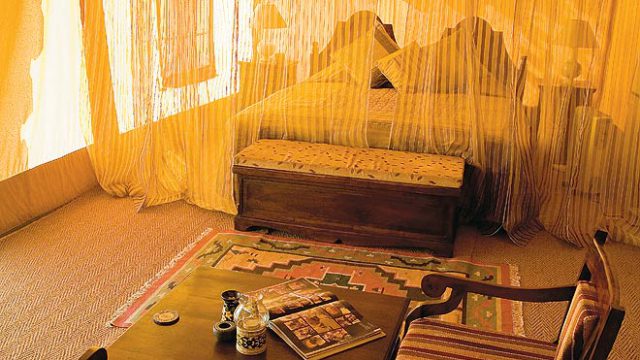

Taj Pashangarh is in a quiet location far away from the main forest, and far far away from mobile phone signals and television sets. I insist on calling home, so the lodge manager points to a slab on the floor inside the dining area and says cheerfully, “Airtel? If you stand on those two stones, you may catch a signal.” The lodge is all stone and earth, 12 cottages set at a comfortable enough distance from each other to ensure that I get lost on the way to mine every time. My favourite location is the gazebo in the stone verandah adjoining the cottage. There, I am surrounded by my own patch of forest, its diverse noises filtering in through the night, sometimes soothing, sometimes scary.

The morning safari begins on a cold note. My teeth stop chattering only when the mist clears an hour later and a large herd of chital appears from inside the foliage. In the pale morning sunlight, the white bark of the aforementioned ghost gum trees takes on an eerie quality. I am the only tourist in the jeep that morning, along with three of Pashangarh’s naturalists. They are gratified at my wide-eyed happiness at just being in the forest. And they are determined to show me a tiger.

The terrain inside Panna is flat and it’s easy to spot animal movement. T2 puts in an appearance early in the morning, her catwalk lasting for over ten minutes. There is none of the usual drama that precedes tiger spotting: frenzied alarm calls in the bushes with corresponding hushed whispers in the jeeps.

With T2’s arrival, there is excitement in the air; park officials are out in full force with their walkie-talkies and tracking devices. T1 has also been spotted in the area recently and we wait to see if she or any of the cubs will emerge. However, it soon becomes clear that the action is over for the day. And so we head off for breakfast.

Panna is one of the national parks with designated areas for visitors to hop off and stretch their legs. Narayana stops the jeep at one of these nooks, overlooking the reserve and the Ken snaking at a distance. The picnic hampers from the Pashangarh kitchen come out one by one, with fresh muffins, muesli, sandwiches and cookies. Fresh fruit and coffee. And the killer deal: warm parathas with two types of achar.

After a mandatory pitstop at Pandav waterfalls on our way, we head back to Pashangarh. I have barely got over my jungle breakfast when it is time for lunch. And lunch at Pashangarh is what they call a light meal, which means a few cold salads, followed by rice, dal makhani and a couple of vegetables. Oh, and some succulent paneer which Chef Kanhaiya grills at the table.

Perhaps because I have come without any expectations, Panna is full of happy surprises for me. For one, there is Dhundwa Seha, the stunning 200-metre gorge formed by the dozens of small canals flowing through the park. The only sounds here are that of a couple of waterfalls trickling down the muddy face of the gorge and the buzz of the vultures high above.

In the din about tigers, Panna’s forest officials have not neglected their native avian species. The latest vulture census has shown that seven types of residential and migratory vultures, including the endangered white-rumped and long-billed species, call Panna home. Their numbers now stand at an encouraging 1,300 and are increasing steadily every year.

Then there is the (almost) secret route through the Hinauta gate (most visitors use the Madla gate off the main road) which, as Narayana promises, is more secluded and spectacular. The undulating terrain on this path with its sharp ups and downs, the tiny river islands where red-wattled lapwings sun themselves in a lazy manner…

And finally, the Ken — or Karnavati, corrupted by lazy British tongues — that plays hide and seek with me throughout the safari, like some of the more friendly fauna. There is also the boat safari on offer but I give it a miss, having no intense desire for up-close and personal encounters with the ghariyal.

Keen to treat Sunday morning with the respect it deserves, I skip the safari on my last day at Pashangarh and lounge over breakfast at my own private verandah. I look up from my book at a sudden sound to see a deer scrambling into the dense shrubbery. Pankaj, the private butler for this cottage, is smiling when he comes by with more coffee. Fresh leopard pugmarks have been found just outside the parking area. At Taj Pashangarh, it’s all in a day’s work.

The information

Getting there

Your best bet is to fly into Khajuraho (about Rs 4,500 one way) from Delhi and take a taxi to Panna (half hour, 25 km; Rs 2,700- 3,000). Or take the convenient overnight Sampark Kranti Express to Khajuraho.

Where to stay

Taj Pashangarh (from Rs 43,600 per person per night, including all meals, two jungle safaris and taxes; tajsafaris.com) is luxury set in 190 acres of wilderness. The Ken River Lodge (kenriverlodge.com) overlooks the river and offers a choice of six huts (from Rs 18,000, all inclusive tariff for two) and six cottages (from Rs 16,000, the same).

The Sarai (from Rs 16,200 per night for double occupancy, including all meals and taxes; saraiattoria.com) is an environment-friendly project close to the Madla entrance of the reserve, with eight independent cottages spread over nine acres.

What to see & do

Take along a good pair of binoculars, since Pashangarh’s naturalists take great pride in pointing out Panna’s ‘ten star birds’ — it also comes handy when the big cats choose to stay hidden in the shrubbery. Boat safaris and occasional elephant-back safaris are available inside the national park, so check with your guide about timings.

The usual suspects on the sightseeing circuit at Panna include the UNESCO world heritage site of Khajuraho, and the Raneh and Pandav waterfalls.

Panna National Park

tigers

wildlife

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.