It happens imperceptibly. A window opens, then another. Curtains are gently parted and then tucked into the

Fontainhas wakes like an ageing courtesan—charming but creaky, what a couple of hundred years could do to any place at the wrong end of history.

To drive by the patchwork heart of Panaji’s Latin Quarter is a sin, a little like driving past Old Goa and ignoring the immense size and stunning interiors of its medieval cathedrals—the remains of Goa Dourada, golden Goa. Unlike that statement, Fontainhas doesn’t diminish a person with sledgehammer show of religion. It’s more like a child’s painting, where surprising flourish is companion to imperfect lines.

There is a romance of discovery in walking through this living coffee table book, leisurely hour-long pace in the morning or before sunset. At other times the noise of the city seeps in, or the sun is too sharp. It wastes the opportunity to capture images without designer sunglasses, and album-making that makes neighbourhood celebrities of amateur photographers and video mavens.

Houses take centrestage—some are robust, many faded, a few going to dust. There is a suggestion of being transported to similar enclaves in Mediterranean Europe, Central and South America, but with the twist of fisherwoman in orange sari and wicker basket frozen against a brilliant blue wall—unique as natural. “Though relatively small, she grew with distinct individuality and an old quaint charm that was quite fascinating,” writes local historian and conservationist Percival Noronha, a resident of Fontainhas for over 70 years. “But it is hoped enough of her old charm will remain to enable posterity to recapture the essence of her 200 years of history.”

Fontainhas is Panaji’s oldest district, sprouting in the early 1800s along with its companion ward of São Tomé, a rabbit warren of faded commerce and time that ends in the north with the polluting spew of Panaji’s arterial road, within sight of the Mandovi river. In the east, it is hemmed by the Ourem Creek, generally an unappetising green-brown channel of bobbing plastic bottles and other urban refuse that merges into marshland further south, along the ward of Portais, a growth of the last century. Between Portais and Fontainhas is Mala, where the fountain that gives the entire district its name, Fonte Fenix, is located, fed by underground springs at the foot of Altinho, the lush hill that cradles the area to the west.

The district, then Palmar Ponte—named for its profusion of coconut palm—grew in response to the decline of Old Goa, gradually spreading into what is modern-day Panaji, a mash of old houses and helter-skelter concrete and neon, teeming offices and shops of sell-by-weight souvenir wear. A one-way umbilical runs across a rise behind Panaji’s still arresting Church Square, and descends into the kindergarten lanes of Fontainhas, coloured, as only the church was traditionally painted white.

As if to echo the gentle lament of Mr Noronha, Fonte Fenix is now nothing. The plaster phoenix head and coat of arms that once crowned the stepwell was destroyed in a burst of nationalism after Goa’s independence from Portuguese rule in 1961. A faded, tattered saffron flag hangs limply there, in the centre of predominantly Hindu Mala. One of the three spouts is choked, another dribbles water along the walls of the decrepit well, and the third pours out onto the muddy floor. Vagrants bathe there, crouched among the small fish and moss. The desperate gather water.

This abandoning of history and heritage is puzzling in an area marked as a conservation zone. The municipality prevents any construction beyond repair. So destitute houses and establishments, stung by poverty, litigation, obstinate tenants who continue to pay less than one hundred rupees a month, or migration to many points before and after Liberation—Bombay, Lisbon, Mozambique, East Africa, Australia, Canada, Britain—sprout vegetation and suffer cracks. They must fall completely before they can be born again, usually as ugly warts.

Fontainhas is seductive with its colour, freeze-frame moments, arches, lace curtains, glimpses of sepia family photographs, vases from China, azulejos, inviting cul de sac. But to be contained by an area that is easily travelled by a forcefully thrown pebble and concentrates Panaji’s proud mestiço, descendants of Portuguese and Goan marriage, is to limit the quirk of discovery. The walk ideally includes Portais, and moves north from the tiny, whitewashed church to St Xavier, where the Ourem creek becomes marshland, and into Mala.

The winding lane—it has a name, 31st January Road, but to call the narrowness a lane is more pleasing—begins its journey into history. The first house to the right, once a mansion, is abandoned for so long that the sidewalk has grown to block entrance to its garage. Further on, at another abandoned house, flick a fingernail across a sticker that urges everyone to vote BJP, on an engraved nameplate, and discover the name of the former occupant, Xencor Xette. The translation in Devnagari script of the Portuguese-flavoured name is provided on another engraved plate across the rusting gate: Shankar Shet.

(And so, Sheikh Ismail is Xec Esmail, Vishwanath V.S. Dukle is Visvonata V.S. Duclo, the Drogaria Royal shares marquee space with Royal Medical Stores, the Estabelecimento de Cera sells church candles, and the tiny, grotty Barbearia Republica with a string of marigold above the entrance invites visitors for budget grooming.)

A turn in the lane, and there is the bakery of Agostinho Soares, recessed and unheralded, unlike J.B. Stores and Bakery in neighbouring Mala, that runs out of its signature poi flatbread in a couple of hours after it’s put out, lush-warm at 4pm. The tiny Fontainhas post office that marks the physical space between Portais and Mala is next, a place where the Catholic staple of O Heraldo—on doorsteps or tucked into door-rings—turns to newspapers in Marathi and Konkani, the Gomantak, the Sunaparant, scores of others, a place where the altars of tulsi predominate over altars of the cross. This demarcation is thankfully absent in the far tighter mesh of São Tomé, home to Fontainhas’ staple eateries like Horse Shoe and Venite, and the boutique and lifestyle stores, Sosa’s and Barefoot, placed like islands of élan in lanes of nuked tar and stone, and insane jumble of crossed overhead wires.

Mala-Fontainhas is also the front of a needless battle zone. In June 2004, excited after an evening of deliberate, rousing speeches, a mob stormed the core of Fontainhas and scored the pettiest of victories, with hammer and chisel smashing a few azulejos, hand-painted ceramic tiles bearing two street names—31st January Road, to commemorate Portugal’s freedom from Spanish dominion in 1640, and another, named after a forgotten crusader. All it did was to showcase nationalist extremism and sharpen the relatively blurred lines of the Fontainhas wards.

The Fontainhas Heritage Festival, a nascent and welcome attempt to showcase the quaint precinct as tourist attraction (the 2005 edition ran 27 November through 3 December) by holding painting exhibitions in houses, showcasing crafts, concerts and cuisine, is seen by some over at Mala as pandering to a Portuguese past. In Fontainhas, there is faint derision for the handful who agree to host exhibitions and have their houses tarted up at the expense of the Municipal Corporation of Panjim; and even those who agree to do no such thing, but their houses are in such visible disrepair that worker gangs are engaged to spit-and-polish the exterior even as the innards are an exhalation away from the past tense. Derision too for a steady stream of advertising filmmakers, movie directors and music video merchants that parachute into Fontainhas to grab a backdrop—a wall with character, a brass band, plaster roosters by a well—and then disappear from this heritage zoo without inmates getting their reward. Some residents openly ask for money, but settle for finesse.

This undercurrent only adds a zesty dynamic to the place, visible with the most cursory sweep of a fingertip to brush away the muck of recent history. Each walk adds a layer to the place, or removes it. Raises queries of the walkabout romantic: Who? When? Why? What the hell happened? Where did they go?

And always, there are more freeze-frame moments within easy walk of the area’s quaint hotels: Panjim Inn, Afonso Guest House, the tucked-away home stay of Park Lane Lodge. Homemade sausage drying on rooftops. Shafts of light from homes, lanterns and streetlamps cutting into the dark. The old men who stake their place by the side of Joseph Bar, doing nothing. The scene at the corner of Gomes Pereira Road in São Tomé is as natural as the derelict ornate building that nestles the rundown bar, homeowners in Portugal.

On Rua Luis de Menezes, the whimsy flash of cacti crowned with eggshells mitigates the architectural obscenity of Hotel Bareton. Tanzania Tailors of C. Fernandes is adjacent to Gurudas Y. Shet’s Fair Price Shop No 2. In the little lane past Casa Lusitana, general merchants, and before the family-run Pakiza Restaurant, maids dressed in green or purple sari worn in the Maharashtrian way diligently wash a tiny car, while a corner away, portly nuns discuss how to fix a damaged wall by the Lar Santa Maria Goretti, a shout away from that glorious nameplate: Tarzan D’Costa, Advocate.

It is fest day of the Church of St Thomas, and the eponymous, short and wide tree-lined street is clothed in cutouts of painted faces and sponsors’ banners—Seagram’s whiskies, Kingfisher’s beer. Mass is underway, and behind, at the snake slim Rua de Natal, Ivo Furtado is oblivious, playing his violin. On a whim, he might invite you into the dark sala of his house, and show off an ancient Hasselblad, or the dusty director’s chair with Gregory Peck written on it, squirrelled away after the shoot of Sea Wolves in Goa, more than 25 years ago.

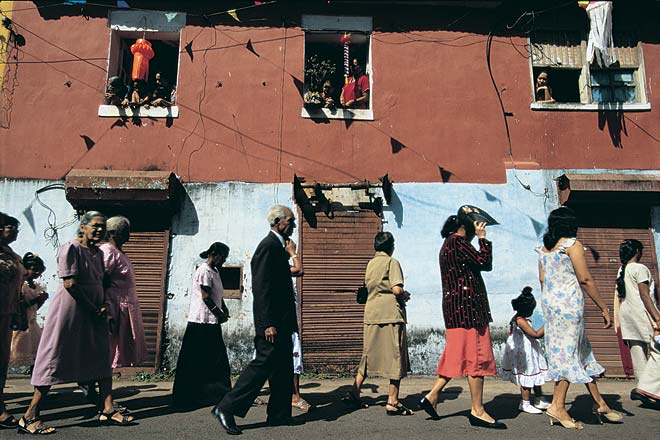

Bandleader Gregory Abreu picks up his ancient, burnished tenor sax, the etched details of its maker still clear: Henri Selmer, 4, Place de Dancourt, Paris. Mass is over, and the flock of a hundred or so prepares for a symbolic procession. Then, with an exploratory pom, Monsieur Selmer’s No 17028 struts the stuff. And they’re off. Children first and last—holding the cross, setting off crackers with incense sticks—in between, a wavering gender divide in Sabbath finery, women first in knee-length dresses, salwar-kameez, pantsuit and sari, and then the men in tie and sombre suit, ambling alternately to Konkani hymns and music by the four-member brass band. A hundred yards down St Sebastian Road, a left turn at 31 January Road for twice the distance, left again at the L-shaped Rua de Natal and back to the church. Slow, wrenching, faintly tragic, stretching the 15 minutes to an age as the neighbourhood lights candles and genuflects.

Ivo stops his violin playing long enough to rush and place candles on the windowsill, as the procession passes. It is wreathed in frankincense from a smoking iron bowl a neighbour has placed on the ground. Then it is over. Just like that. The seasons of a day in Fontainhas.

The information

Where to stay: Hotels in Fontainhas are typically small and charming. Afonso Guest House on St Sebastian Road (0832-2222359) has eight rooms. Ask for any of the four street-facing rooms. Panjim Inn on 31st January Road has 14 rooms with dark furniture and four-poster beds. Across the road, the same management runs Panjim People’s, a more lavish spread of four rooms on top of a gallery. The nearby Panjim Pousada, also run by the same people, has nine rooms. Reservations for all three at 2226523, 2227169 (www.panjiminn.com).

Where to eat: The hotels specialise in food that would count an extra pinch of pepper as pungent and spicy. The Panjim Inn family is suitable for the unavoidable breakfast, tea, coffee, juice and drinkies on the verandah—nice to see life go by. For local taste with Portuguese overtone, head to the excellent Horseshoe, on Rua de Ourem. Pester chef Vasco for signature dishes ranging from grilled fish and prawn balchao to steaks topped with egg. Open for lunch and dinner, except Sunday (2431788). Behind Afonso Guest House is the tiny Viva Panjim, where flavours are local and earthy, and the service sleepy. The chonak (bekti) and chicken xacuti are worth the wait. Open 8.30am-10.30pm with a siesta timeout between 3.30 and 7pm (2422405). At the north end of 31st January Road is Venite. Soups and pasta are good, and seafood, which runs from stuffed crab to grilled barracuda, is great. So is the house feni and caramel custard. Chat with Luis, the easy-going properietor, for a more lavish pre-ordered three or four-course spread. Open all day (2425537). For a taste of budget Hindu Goan food, there’s the calendar-art Ananda Ashram across Venite. Wholesome thali, fish curry and rice and plump fried mackerel. Lunch and dinner, no alcohol. Look for pushcarts along the nooks and crannies of Fontainhas in the evening, for beef, pork and chicken stuffed in Goan bread.

This and that: Adjacent to Panjim Inn is Velha Goa (0832-2426628), super for azulejos, Portuguese-style hand-painted glazed tiles, tables and other bric-à-brac. Barefoot is a great home store, next to Venite.

Latin Quarter

Places to see in Goa

places to visit in Goa

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.