Michael Ondaatje tried to warn us, he really did, but I wasn’t listening hard enough: “All this

This is where one story of Sri Lanka begins, with Pandukabhaya, a prince hunted by his uncles, befriended by yakshas and bhoots, who won his spurs in a grisly battle. The Mahavamsa recounts: “When the prince saw the pyramid of skulls, where the skulls of his uncles lay uppermost, he said: ‘Tis like a heap of gourds’; and therefore they named (the place) Labugamaka.” But the city he founded, which would last for over 1,500 years before the kings of Sri Lanka shifted to Polonnaruwa, was called Anuradhapura after Pandukabhaya’s great-uncle, Anuradha, who was presumably too bright to fight a warrior who had yakshas at his beck and call.

The old cities of Anuradhapura blend seamlessly into the new; ruins rise from the forests, from behind new buildings, from the sidewalls of teastalls. This is tourist hell, if you’re on a rigid timetable, a nightmare of signs pointing to the ancient tank decorated with rearing king cobra heads where schoolchildren splash around; the pristine dagoba, white against an eggshell blue sky, where a tired monk sleeps against its huge silhouette, his robes fluttering in the strong wind; the famous moonstone, its carvings gleaming in the sun; the barnacle cluster of buildings at Isurumuniya where the sculpted form of The Man and His Horse compete for attention with a frieze of two lovers.

It isn’t all poetry in stone. Outside the shrine to Sri Maha Bodhi, the sacred Bo tree whose seed was exported to Sri Lanka along with the teachings of the Buddha, the flow of the long line of votive lamps, black with years of grease, is broken by metal detectors. In 2002, while pilgrims were at prayer during a major festival, LTTE troops opened fire, killing 80 people.

I’m trying to make sense of all this; history, guide maps, stumbling tourists caught unprepared like us by the quiet, unobtrusive but unignorable scale on which Anuradhapura unfolds. Then I feel a gentle tug on my T-shirt and look down to see a tiny, old bird-like bhikkuni in maroon robes and ancient Reebok sneakers. Her eyes are gleaming with curiosity, but we have no language in common; she frowns, then points to the dagoba in the distance. “Bee-yoo-tiful?” she says questioningly. “Beautiful,” I agree. I offer her a Polo mint, she reciprocates with slices of raw mango, and we share this odd meal in perfect accord.

The rock fortress of Sigiriya is a reminder that history rarely chronicles the doings of peaceniks. King Kassyapa, the man who built this massive complex out of a 600-foot high rock, dealt with the usual father-son disagreements by bumping off his dad, King Datusena. Sigiriya was built in the shape of a crouching lion; only the paws, the toenails long, curved and oddly manicured, survive, but to ascend the fortress you must go up through what used to be the lion’s throat.

Scores of schoolchildren rampage cheerfully up and down a vertiginous staircase cut into the rock (they’re everywhere, as though the school board of Sri Lanka has decided to swap monuments for classrooms). They giggle at the maidens of Sri Lanka, immortalised in vivid frescoes on a wall below the lion’s paws, and giggle even harder when the guide points out a mistake where the artist added an extra nipple to an already well-endowed bosom. The palace-fortress was turned into a monastery when Kassyapa died, and the monks disapprovingly destroyed most of the frescoes. I’m not sure the artists would have been pleased to learn that of all their work, what’s been preserved includes the three-nippled error.

From atop the fortress, whipped by the breeze, what comes into relief are the fortifications, the watch-points, the 360-degree view of the plains ringed by hills. That lion has long since crumbled into dust, but if it could speak, what it would say is, only the paranoid survive. Kassyapa died almost by accident: riding into battle, his elephant turned aside at a swamp. His armies assumed the king was injured or dead, and fled in terror. According to legend, the king, betrayed by a marsh, killed himself rather than be taken captive.

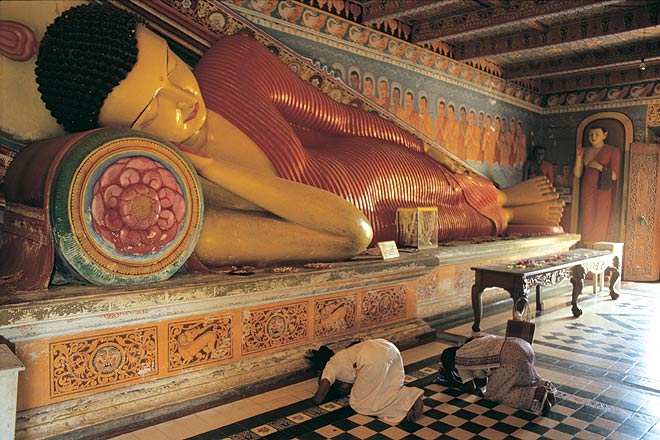

There’s a point in any trip where, tourist or traveller, serendipity intervenes; and since Sri Lanka is the place where the word was coined by Hugh Walpole, for ‘Serendip’, island of peace and unexpected, fortuitous happenings, it must happen here. We begin to meet the Buddha on the road, as if He’s decided to rework the itinerary. In Dambulla, a contemporary statue of the Buddha in shrieking gold, decorated with crude pink lotuses, can’t detract from the majesty and harmony of the images in the five cave temples.

The first temple was carved into the rock by a refugee king, and some of his loneliness seems to have infected the sleeping figure of the Buddha enshrined in stone here, around 1 BC. In the second cave, the drip of water from the ceiling, collected and used for sacred rituals, is all that’s audible as spectacular images the monks had the real Tooth hidden away safely, so what the Portuguese destroyed was just a replica. (Incisor, canine or molar? Blasphemy, but I can’t help wondering.)

No one knows the whole truth, but everyone believes that nothing but the Tooth is ensconced in Kandy’s temple. I see the devotion shining from the eyes of worshippers, the care with which even the humblest lotuses are added to the heap of flowers to form a pattern, and I realise it doesn’t matter.

The evening in Kandy is magical, with the lights of the town softly glowing in the mist from the river; the city provides the pause, the space for reflection that even the most driven tourist needs. It’s almost possible to forget the twin frescoes in the temple. The first, ancient, beautiful, is torn to bits, spattered with bullet holes, the souvenirs of a 1998 bombing of the temple by the LTTE; the second is a perfect replica of the first, hanging defiantly beside the tattered original.

But the next day brings peace in the form of elephants, at the Pinnawala Orphanage for pachyderms. The herd splashes in the river, the mothers protecting the two youngest calves from too much roughhousing; they beg furtively for bananas when the mahout isn’t looking and sulk when it’s time to leave the water, their trunks swaying in complaint as they lumber up the track. One limps along on three legs; the fourth was blown away by a landmine.

Later, in Galle, the severe beauty of the Dutch Reformed Church, with its antique church organ, is undercut by the sign that refers to the “188 members” who “had their own churchchairs, carried by slaves”. Galle is impatient to move on from the tsunami, though on the road from Colombo, we see the signs touting ruined trains and destroyed villages, tourists videotaping each other’s offerings of chocolates and chips to the hard-eyed children of Thalwatta who can speak English: “Hello! Help? Tsunami. Money?” Galle stadium was smashed into pieces; but the Fort next to it is intact, the “umbrella lovers” cuddling on its walls under the cover of sunshades. It is, we are informed, because of their “goings-on” and “what-all” that the Lighthouse of Galle is now closed to tourists.

Back in Colombo, a corpse has been found in Cinnamon Gardens; the mystery unravels to reveal an underworld killing worthy of Bombay. We relax that evening with the wonderful couple who runs Barefoot, a café, gallery and shop rolled into one; we watch Dominic Sansoni’s stark film on war-torn Sri Lanka; we listen to old rock ‘n’ roll standards at a local nightclub.

No tourist could “do” Sri Lanka in a week; the real country is caught somewhere between the war stories and those ageless Buddhas. Perhaps it’s to be found in Kelaniya, the Buddhist Maha Vihara outside Colombo where the Buddha preached 2,000 years ago, where the ceilings tell fantastical stories and the gods are shrouded in veils of the lightest gauze, where a young boy monk talks excitedly about his months of study in the UK, where rows of pilgrims chant, their faces illuminated in the gathering night by flickering flames from oil lamps.

Perhaps it’s lurking in Michael Ondaatje’s sensuous poetry about monks who came down the rivers and the indelible scent of cinnamon, or in Carl Muller’s rambunctious prose about Burgher life, or Shyam Selvadurai’s thoroughly modern tales of Colombo. Or perhaps all I was looking for was an elephant with a taste for slightly raw bananas, his spine curved into a question mark with the effort of getting by on three legs, who has to limp to get anywhere at all. But he gets around all the same.

places to visit in Sri Lanka

Sinhala history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.