At the centre of the kitchen stands a barrel with the letters BBQ boldly highlighted across it.

All at once the lights dim, an upbeat instrumental tune fills the air, and four chefs burst on to the scene — their bodies in perfect rhythm with the music. Incandescent spotlights follow their movements as they seize any utensil in sight — woks, plates, glasses, knives, spoons, forks, chopsticks — and within moments transform these banal objects into instruments that create music in the sweetest harmony.

It’s 5pm and I am at the Nanta Theatre in Seoul where I am witnessing one of their most popular theatre performances in recent years. Language isn’t a problem, as this show isn’t reliant on dialogue. Instead, through the rhythmic beating of knives against chopping boards, the clinking of spoons against glasses and the deeper drumming of brooms against dustbins, the ‘chefs’ of this non-verbal production tell the comedic story of a smarmy restaurant manager who has set his puckish staff the impossible task of preparing a wedding banquet in one hour. Music isn’t the only medium employed here. What starts out as an orchestra eventually turns into a full-fledged choreographed stage show, as the artistes dance, leap and somersault across the stage, chop vegetables with singular rapidity for fantastic visual effects, and juggle fine bone china with dexterity — all in a synchronised response to the music. And while my guide informs me that this is a contemporary take on the traditional Korean percussion performance — Samulnori, which employs drums and gongs for a distinctive sound — I can’t ignore the truth that at the heart of this production lies a more familiar, and more celebrated, Korean tradition: food.

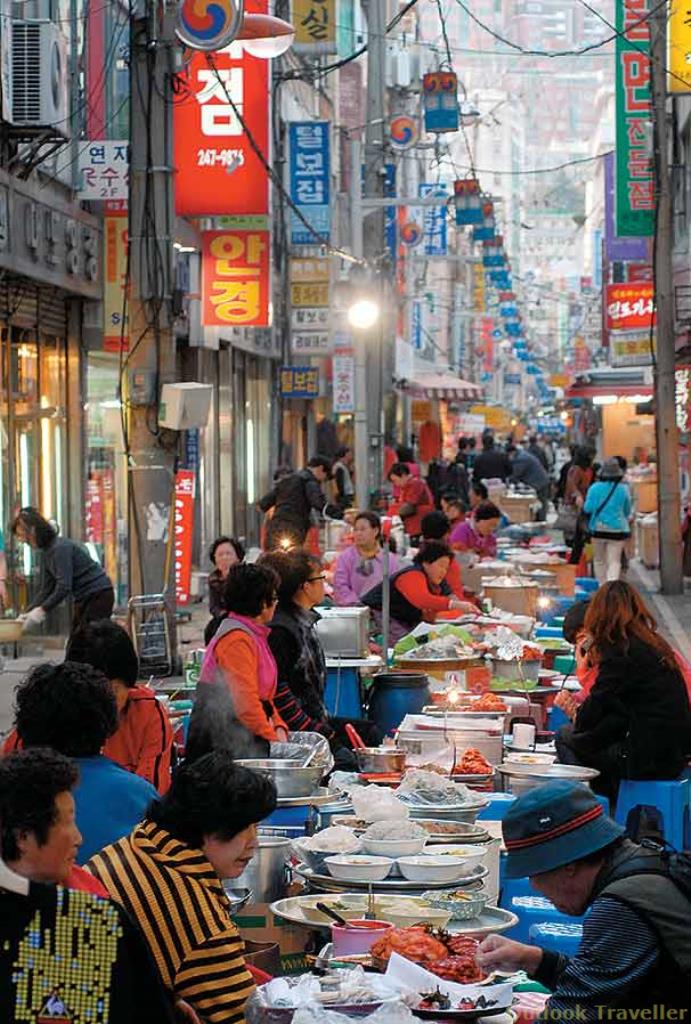

That food is a way of life in South Korea is evident everywhere — from the ubiquitous barbecue joints and the innumerable street stalls purveying every manner of dried seafood to the big, bustling markets overflowing with kitchen utensils and earthenware crockery (too pretty to eat off), and as I will discover later, the ‘fish restaurants’ of Busan, South Korea’s second-largest city after Seoul, where entire streets are dedicated to seafood-only restaurants.

“All our meals, including breakfast, typically have some seafood in them,” says Tommy, our guide, pre-empting my query on their diet. As with a lot of countries, Korea’s geography explains its cuisine: a mountainous peninsula that offers a climate ideally conducive for rice (another staple), soybean and a host of fruit and vegetables. However, Western influences, particularly in the last century, have led to an increased protein-rich diet, with Koreans now heavily incorporating beef, pork and chicken into their meals.

Clearly, I have a lot to learn. Especially, that Korean cuisine goes far beyond kimchi (pickled vegetables) and its famous barbecue; that it traditionally encourages communal dining where everyone partakes of a common main dish, and that given the fact that dinner-time here means 6pm, we’re an hour late. I begin with the obvious — the barbecue — and let Tommy guide me to Arumso, an unpretentious bulgogi (ribs) speciality joint in the heart of town with bright, noisy interiors. Simple wooden tables, fitted with built-in grills, enable you to prepare your own meal. I opt for the beef bulgogi (14,000 won/Rs 522) — if it’s bulgogi, it has to be beef — and before I can say chopsticks, an energetic chef is arranging tender strips of marinated meat on our grill. Moments later a wave of tiny platters comes pattering down on to our table, proffering banchan or the accompaniments essential for a Korean barbecue. The task seems easy enough: take a firm, crunchy piece of lettuce, add a spoonful of sticky rice along with your choice of condiments from the selection presented before you (I recommend at least the garlic cloves, red bean paste and soya sauce) and some sizzling strips of freshly grilled beef before wrapping it all up into one neat parcel. I eye Tommy as he adroitly pops roll after roll into his mouth, while I struggle to construct my first. Four rolls later for Tommy, and I’m ready for my first real taste of Seoul food: a slightly soggy, overstuffed roll from which my beef-rice mix plops clumsily on to my plate the second I lift it. I concede defeat, grab a fork and shovel everything at one go into my mouth. I’m not sure you’ll believe me if I say that it’s the best kind of barbecue I’ve ever had.

The next day, I wake to a bitingly cold morning — unseasonable weather for April in Seoul when ordinarily the delicious warmth of the spring sun welcomes the delicate cherry blossoms. Instead, weak rays fight their way through a blanket of grey and an icy wind forces me to wrap my jacket tighter as we make our way to Namdaemun market, one of Seoul’s largest markets. “You’ll find everything here,” claims Tommy. “Also a good place to sample street food.” He wasn’t kidding. From the moment you enter, carts groan under the weight of dried squid and crackly flavoured seaweed (favourite snacks), vendors peddling an array of Korean fast food, and stalls grilling various meats to be added to piping hot broths. A man selling what look like meat lollipops catches my eye and I try a stick of delicious fried crabmeat bathed in wasabi soya sauce (1,000 won). The rest of the labyrinthine place is a jumble of tacky ‘high-fashion’ apparel, dubious sporting gear and souvenirs; sensing my lack of interest, Tommy suggests we move on to the more tourist-worthy Changdeokgung Palace.

A World Heritage Site, the palace was built between 1405 and 1412 during the Joseon era, the last royal dynasty of Korea. The Koreans attribute the modern face of their country to this dynasty, which has apparently shaped their culture, language and etiquette as you see it today, aside from giving them the royal court cuisine. Rice and soup form the core dishes, which are traditionally accompanied by 12 smaller dishes served in bronzeware. It’s a two-hour walk to explore the palatial grounds where wooden pagoda-style structures in muted shades and gently sloping black tiled roofs are the defining elements of the architecture.

It’s meal time again, and Tommy selects Jeonju Bibimbap, not too far from the palace. An apt choice, I think, as I learn that bibimbap — a steaming hotpot of rice/noodles mixed with vegetables and crowned with a fried egg — has descended from the royal dish goldongbang. The menu is brief and I can’t spot bibimbap among its limited offerings. But then the menu is in Korean, and the only help is via English descriptions like “tasty bombs which will explode and get your saliva juices flowing”. Tommy isn’t much help either; everything is either “delicious” or “traditional” or both in his opinion. He does nonchalantly inform me, though, that this place doesn’t serve bibimbap! I opt for the “special combination — tastebud’s delight”, which turns out to be a cold flavoursome broth with buckwheat noodles let down only by the lack of beef (6,500 won). “This is how it’s traditionally served,” says Tommy, as I look disappointedly at the lone piece of meat, lost in the tangle of noodles. Unsatisfied, I ask for more. I know I’ve offended the waitress even before I finish my sentence. She scowls, disappears and returns with a platter half full. Hardly the royal meal I had hoped for.

Later that evening, I find myself in Insadong street, a quaint area in downtown Seoul that offers an appealing mix of boutiques, artefacts, antiques and upmarket restaurants — a world apart from the raucous Namdaemun market. I meander through the lanes where window displays and shop fronts are designed to catch the eye as their merchandise virtually spills out on to the pavements. I’m tempted to bargain but decide against it; language is a barrier here. Beside, it’s way past dinner-time. Eager to make up for the afternoon with promises of a truly traditional Korean culinary experience, Tommy takes me to Eunjung, in the vicinity. We’re asked politely to remove our shoes by a kindly lady who leads us into a private dining area — non-fussy and clean — where low dining-tables and floor seating await. The menus are fixed sets, as with most places here, and unable to tell the difference I pick the one priced at 17,000 won. Within five minutes our table is inundated with dozens of little platters: komak (mussels encrusted with sesame seeds); chaejab (delectable glass noodles with seaweed and mushrooms); jijim (spicy rice pancakes); teokgalpi (meltingly tender beef medallions) and the requisite broth (this time a hot, spicy shellfish version with octopus, shrimp, crab claws, greens and, of course, rice). Fittingly, this feast ends with sujeong gwa — a chilled, potent cinnamon drink, consumed in olden times by the royal family as dessert.

My fourth day in Korea sees me heading to Busan, 450km away, but the superfast train gets us there in just under three hours. Busan, or Pusan, is warmer and prettier than Seoul. Maybe it’s the beaches, maybe it’s the hot springs and the parks or maybe it’s simply that the cherry blossoms are in full white bloom, forming gentle archways over the streets. Busan is also Korea’s largest port city. The Jagalchi wholesale fish market is one of the city’s biggest tourist draws, and it’s easy to see why. Endless rows of sea creatures — both live and freshly killed — stretch out before me as I gingerly pick my way through the watery lanes, dodging the odd octopus that has jumped out of its tank in an attempt to swim for its life. I learn that this market exports its best stuff to Japan before supplying it to the local markets. A fact I find hard to believe when we arrive at Haeundae street where, as far as the eye can see, water tanks at the entrances of each of its ‘fish restaurants’ display those unfortunate denizens of the sea that are to eventually become our meals. Word of warning for vegetarians: pack your own meal or be prepared to settle for some dried seaweed to keep you going.

The service at Shin Haeundae is brisk, even brusque — something I have got accustomed to in Korea. A pungent aroma announces the arrival of my maeun tang, a fiery fish and tofu broth served with rice and followed by a trail of accompaniments (10,000 won). “Indian cuisine is similar, no?” says Tommy, devouring his lunch. “Spicy with lots of stews, and also an integral part of your culture.” I burst out laughing. “Well, I guess that’s one way of looking at it,” I respond. But as I sit there, sated after my meal, I contemplate Tommy’s statement. I’ve been here four days sampling the cuisine and by the time I leave tomorrow I would have eaten bibimbap, knocked back shots of soju (their traditional rice wine), and even tried silkworms. But it’s still not enough to understand fully the intricacies of this cuisine and to describe its vastness and variety, history and traditions in a single article. Perhaps Tommy is right; perhaps there is a big similarity between Indian and Korean cuisines.

Korean food

Seoul

Street food culture in South Korea

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.