It’s a bit of a haze now, but I swear I knew precisely what I was

I embarked on my journey to Bukhara with some trepidation. It had taken me a while to get there — the restaurant was in the throes of its 35th anniversary celebrations, which in the life of a restaurant is a staggering moment. The hype had been deafening — for years Bukhara has made it to the list of the world’s top 50 restaurants and is a four-time winner of Restaurant magazine’s Best Indian Restaurant in the World award. Every visiting worthy breaks roti here — David Cameron even stormed into the kitchen to learn the finer points of making the roti. They don’t even offer reservations in the evenings — it’s just first-come first-serve. And they just keep coming. Frankly, I was worried I’d be disappointed. After all, how good can a kabab-roti joint be?

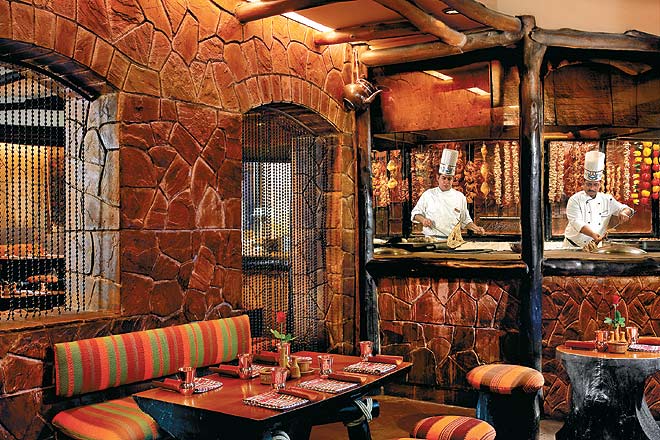

Cocooned in a wing off the ITC Maurya’s iconic Krishen Khanna lobby, Bukhara’s décor is so unremarkable it raises eyebrows. Stone walls. Painted logs holding up the roof. Utensils dangling from the rafters. Low, upholstered stools. The servers in pathan suits. A caravanserai on the Silk Road, perhaps. Or a five-star dhaba.

Bukhara turns every rule on its head, which is why its success is intriguing. In an age of tapas-sized attention spans, you’d imagine a restaurant would need to reinvent itself constantly. But Bukhara has not changed its (rather modest) menu once since it fired up the tandoors (only now have a couple of new dishes been introduced — sadly untested). Their press release calls Bukhara the Rock of Gibraltar. There’s no pandering to Western palates, and the food has just the right hint of heat. Unless you insist otherwise, you’re expected to eat with your hands. They don’t serve rice. They wrap you in an apron, which might be great for your clothes but doesn’t exactly evoke fine-dining. The tableware, which instantly reminded me of India Coffee House, hasn’t changed in 35 years either.

And yet it’s extremely successful. Over the past 35 years, Bukhara has sold over 10 lakh murgh malai kababs, over 25 lakh dal bukharas, over 15 lakh seekh kababs and over 5 lakh naan bukharas.

The first thing you’ll notice about the food is the generous portion size (but at those prices they have to be generous). The menu, as mentioned, is short. In the line of duty, I demolished most of it, though the average diner might order only a few things and be perfectly sated.

The walls at Bukhara are adorned with kilims so gorgeous you could eat them. But the kababs were really very good, which is probably why the kilims are still intact. The standouts among the vegetarian options were tandoori aloo, tandoori cauliflower and tandoori shimla mirch. Among the non-vegetarian offerings, the prawns, and the murgh malai and barrah kababs and the off-menu chicken khurchan were absolutely stunning. And yet there was nothing poncy about these full-bodied beasts. Guess it comes with the terrain (in this case the cuisine of the northwest frontier, though there are those who dispute such a cuisine even exists). The slivers of sikandari raan — a whole leg of lamb cooked in the oven — were melt-on-the-tongue soft. And then there was the legendary dal bukhara, slow-cooked overnight on a coal fire and served with a dollop of butter. I requested several helpings and asked for some to be packed. The dessert menu was uncomplicated. But they served me the best gulab jamun I’ve ever eaten. Ditto the phirni.

Helming Bukhara is its soft-spoken executive chef, J.P. Singh, who runs his kitchen with the precision of a scientist. Ask him the secret of Bukhara’s success and he’ll tell you it’s standardisation and consistency. They’ve perfected the recipes and they’re sticking to them. The specific proportions of masalas in the marinades are sacrosanct. The ingredients, particularly meats, are secured from trusted sources. Even the prawns have to be a minimum of 80 gms to be deemed worthy of the Bukhara tandoor. But if cooking were a science, every restaurant would be a Bukhara. After all, when the raw kabab hits the tandoor, it’s that elusive sense of andaaz that comes into play. And under J.P. Singh’s watchful eye, they are consistent about that too.

I haven’t even mentioned the nicest thing — and it’s not the food. Bukhara is an utterly unselfconscious restaurant. You might expect some tedious choreography, an atmosphere charged with culinary drama. Instead, you will just sink into your seat, relax and let the chefs work their magic — quietly. The hype’s on the outside. Inside, there’s nice food, warm service and the making of memories. Which reminds me — mine needs jogging.

ITC Maurya

New Delhi

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.